Algonquin Among First American Ships Lost In World War I

By James Donahue

Historians remember the torpedoing of the White Star liner Lusitania as among the key events driving the United States to declare war against Germany. But the Lusitania, which went to the bottom in May, 1915, was not the first or last of a long list of vessels lost to German raiders and U-boats before President Woodrow Wilson and Congress agreed to join the war in April 1917.

Strangely it was the sinking of the American steamship Algonquin, which went down west of Bishops, near the Scilly Islands, Great Britain, on March 12, 1917, that seemed to have been among the “last straws.”

Here is what happened. After two and a half-year-old stalemate on the European battlefield, the German high command on January 31, 1917 declared unrestricted submarine warfare against all shipping, neutral or belligerent, carrying cargo for Britain.

Remember that the Lusitania was already a victim of the war. That ship was a British vessel, laden with American passengers, and it was rumored that it was carrying military munitions on its lower decks. The sinking caused harsh sentiment in the American Press against Germany.

Once the Germans declared war against all vessels, President Wilson broke diplomatic relations with Berlin but did not ask Congress for a declaration of war. Even though there had by then been at least 10 U.S. merchant vessels attacked, he reasoned that these were not overt acts committed against American ships. He asked instead to arm American merchant ships in the hope of holding back further attacks.

On Feb. 24, British intelligence intercepted a telegram from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to Mexican authorities proposing a German-Mexican alliance in a war against the United States. Zimmermann proposed that the war might help Mexico recover territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona lost in the Spanish-American War.

Thus tensions were mounting and America was being drawn into the great war raging in Europe, in spite of our government’s efforts to stay neutral.

The Algonquin became the first of five American ships lost to the Germans after that declaration. It was sunk by U-62, 65 miles west of Bishops, off the Scilly Islands, on March 12. It was followed by the sinkings of the City of Memphis, Vigilante and Illinois on March 18, and the Healdon on March 21.

War was declared against Germany on April 6.

So the Algonquin was not the first American merchant vessel sunk by German U-boats in that conflict. That honor, if you can call being torpedoed an honor, went to the Gulflight, sunk on May 1, 1915. News of the incident was virtually lost under the story of the Lusitania and the loss of 1,198 lives, including 128 Americans, only one week later.

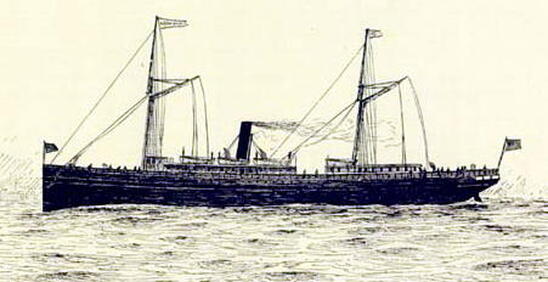

There were records of events involving the Algonquin over several years, indicating that this ship was an active merchant vessel, with cabins for limited passenger service. It made regular trips between Philadelphia and various European ports prior to the war.

The Algonquin was among the first ocean vessels to have ship-to-shore radio. And like the historical radio message from the Titanic, when the Algonquin broke a tail-shaft in the midst of a winter blizzard off the U.S. Atlantic coast, the radio signal C.Q.D. was used to summon help.

The call was answered by nine other ships all in the general area. The skipper of the Algonquin chose the closest vessel, the San Marcos, to come to his aid and dismissed the others with a thank-you message. The San Marcos towed the Algonquin safely into Charleston.

There is one other story to be told about this ship. It seems there were two brothers, identified only as Seymour and George, who served as members of the Algonquin’s crew on the day it was destroyed.

As the story goes, the brothers were changing shifts, one going on duty and the other coming off, and they stopped on deck to chat just as the torpedo hit. They both survived the attack but were rescued by different vessels. One was taken to England and the other brother was taken to North Africa. They were not aware that the both survived the attack until weeks later after they had both written home.

By James Donahue

Historians remember the torpedoing of the White Star liner Lusitania as among the key events driving the United States to declare war against Germany. But the Lusitania, which went to the bottom in May, 1915, was not the first or last of a long list of vessels lost to German raiders and U-boats before President Woodrow Wilson and Congress agreed to join the war in April 1917.

Strangely it was the sinking of the American steamship Algonquin, which went down west of Bishops, near the Scilly Islands, Great Britain, on March 12, 1917, that seemed to have been among the “last straws.”

Here is what happened. After two and a half-year-old stalemate on the European battlefield, the German high command on January 31, 1917 declared unrestricted submarine warfare against all shipping, neutral or belligerent, carrying cargo for Britain.

Remember that the Lusitania was already a victim of the war. That ship was a British vessel, laden with American passengers, and it was rumored that it was carrying military munitions on its lower decks. The sinking caused harsh sentiment in the American Press against Germany.

Once the Germans declared war against all vessels, President Wilson broke diplomatic relations with Berlin but did not ask Congress for a declaration of war. Even though there had by then been at least 10 U.S. merchant vessels attacked, he reasoned that these were not overt acts committed against American ships. He asked instead to arm American merchant ships in the hope of holding back further attacks.

On Feb. 24, British intelligence intercepted a telegram from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to Mexican authorities proposing a German-Mexican alliance in a war against the United States. Zimmermann proposed that the war might help Mexico recover territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona lost in the Spanish-American War.

Thus tensions were mounting and America was being drawn into the great war raging in Europe, in spite of our government’s efforts to stay neutral.

The Algonquin became the first of five American ships lost to the Germans after that declaration. It was sunk by U-62, 65 miles west of Bishops, off the Scilly Islands, on March 12. It was followed by the sinkings of the City of Memphis, Vigilante and Illinois on March 18, and the Healdon on March 21.

War was declared against Germany on April 6.

So the Algonquin was not the first American merchant vessel sunk by German U-boats in that conflict. That honor, if you can call being torpedoed an honor, went to the Gulflight, sunk on May 1, 1915. News of the incident was virtually lost under the story of the Lusitania and the loss of 1,198 lives, including 128 Americans, only one week later.

There were records of events involving the Algonquin over several years, indicating that this ship was an active merchant vessel, with cabins for limited passenger service. It made regular trips between Philadelphia and various European ports prior to the war.

The Algonquin was among the first ocean vessels to have ship-to-shore radio. And like the historical radio message from the Titanic, when the Algonquin broke a tail-shaft in the midst of a winter blizzard off the U.S. Atlantic coast, the radio signal C.Q.D. was used to summon help.

The call was answered by nine other ships all in the general area. The skipper of the Algonquin chose the closest vessel, the San Marcos, to come to his aid and dismissed the others with a thank-you message. The San Marcos towed the Algonquin safely into Charleston.

There is one other story to be told about this ship. It seems there were two brothers, identified only as Seymour and George, who served as members of the Algonquin’s crew on the day it was destroyed.

As the story goes, the brothers were changing shifts, one going on duty and the other coming off, and they stopped on deck to chat just as the torpedo hit. They both survived the attack but were rescued by different vessels. One was taken to England and the other brother was taken to North Africa. They were not aware that the both survived the attack until weeks later after they had both written home.