Mohawk Takes 49 To Bottom After 1935 Collision

By James Donahue

The Mohawk collision was the last in a string of three ship disasters that ruined the mighty Ward Line of passenger vessels in the midst of the Great Depression. The first was the Morro Castle fire off Asbury Park, and then the Havana grounded on a Florida reef.

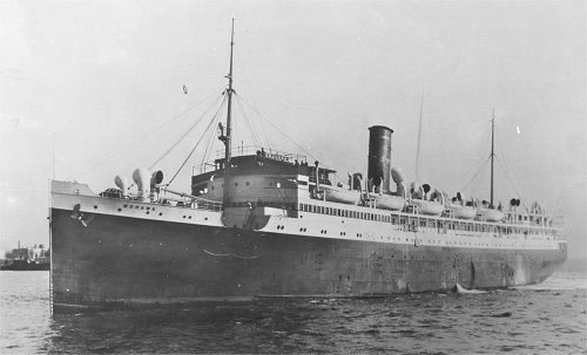

The ten-year-old steamship Mohawk, leased from the Clyde Line to replace the Morro Castle, sank on Jan. 24, 1935, after a steering problem caused the vessel to veer into the path of the Norwegian freighter Talisman off the New Jersey coast.

Bitter cold, ice and snow hampered the evacuation of the 160 passengers that night, so 45 lives were lost, including Captain Joseph Wood and all but one of the ship’s officers.

One of the survivors, Sarah Jackson Smith, later described the disaster in her memoirs. She told of how she and her husband, Sam, nearly missed the departure of the Mohawk that cold winter day because of ice that made crossing the Brooklyn Bridge hazardous. They reached the dock in time, however, and Smith said she went directly to their stateroom and went to bed because she always got seasick when she traveled on ships.

She wrote that during the brief time she was on deck "I had remarked to Sam that all the lifeboats seemed to be buried in snow on the decks.

"Four hours later there was a terrible jolt followed by the complete standstill of our ship. Sam came running in and said we were rammed by a Norwegian freighter. He assured me that everything was under control. I put my coat over my pajamas and adjusted the life belt. We started through a passage to go to the deck."

As they were going up the steps to the deck the Smiths met a seaman who had no lifebelt. "I went back with him and gave him a second one which I had seen under my berth." Then on their second trip toward the deck, she said they met a woman who was returning to her stateroom for her jewels. She said this woman was one of the 49 people who died that day with the Mohawk. She was later found floating in the sea, and wearing her jewels.

Smith said they had to dig the lifeboats out of the snow and ice by hand, and then hoist them out on the ship’s davits. "In those days they were not lifted by machinery. By this time, we were aware that a great gash had been made in our side and the ship was beginning to list. We finally raised one lifeboat, got it down the side of the ship and started to move away. The lifeboat was filled to capacity with passengers and a few crew."

As they attempted to push the boat away from the side of the sinking liner, however, they discovered that it was still tied to the Mohawk. "A crew member started to shout for a knife to cut us away. Sam called to him to tear his coat open and pull out a gold penknife he had in his pocket. . . As it was two degrees below zero, Sam’s fingers were already frozen. The seaman found the knife, ran and cut us loose from the Mohawk.

"We rowed away as quickly as possible, and had hardly gotten at a safe distance when we witched with horror – the Mohawk sinking with 49 people aboard, many of them young. Had we not gotten away when we did, we would have been sucked in with the Mohawk as she sank."

Smith said they were picked up by the Mohawk’s sister ship, Algonquin, several hours later and taken ashore where they were met by newspaper reporters, cameras and hounded with "endless questions."

During an inquiry, it was learned that the steering system failed on the Mohawk at about 9 p.m., shortly after the ship left New York harbor, but that the crew continued on anyway, switching to a manual steering system that required communication between the bridge and the engine room. Not long afterward, a mix-up in orders from the bridge caused the engine room crew to execute a hard turn to port, running the ship at full speed directly into the path of the Talisman.

The Talisman struck the Mohawk broadside. The gash in the ship’s steel hull might not have been enough to sink it had it not been for something else that the company had done prior to the collision. Because of the depression, and in an effort to squeeze some extra revenue out of the ship, the watertight bulkheads had been opened for easier loading and unloading of cargo. With all of the bulkheads opened, the ship was doomed the moment her hull was breached.

The 387-foot-long steamer was one of four sister ships built a decade earlier for the Clyde Line. The three identical sisters were the Algonquin, Cherokee and Seminole, all names of Native American tribes in the United States.

By James Donahue

The Mohawk collision was the last in a string of three ship disasters that ruined the mighty Ward Line of passenger vessels in the midst of the Great Depression. The first was the Morro Castle fire off Asbury Park, and then the Havana grounded on a Florida reef.

The ten-year-old steamship Mohawk, leased from the Clyde Line to replace the Morro Castle, sank on Jan. 24, 1935, after a steering problem caused the vessel to veer into the path of the Norwegian freighter Talisman off the New Jersey coast.

Bitter cold, ice and snow hampered the evacuation of the 160 passengers that night, so 45 lives were lost, including Captain Joseph Wood and all but one of the ship’s officers.

One of the survivors, Sarah Jackson Smith, later described the disaster in her memoirs. She told of how she and her husband, Sam, nearly missed the departure of the Mohawk that cold winter day because of ice that made crossing the Brooklyn Bridge hazardous. They reached the dock in time, however, and Smith said she went directly to their stateroom and went to bed because she always got seasick when she traveled on ships.

She wrote that during the brief time she was on deck "I had remarked to Sam that all the lifeboats seemed to be buried in snow on the decks.

"Four hours later there was a terrible jolt followed by the complete standstill of our ship. Sam came running in and said we were rammed by a Norwegian freighter. He assured me that everything was under control. I put my coat over my pajamas and adjusted the life belt. We started through a passage to go to the deck."

As they were going up the steps to the deck the Smiths met a seaman who had no lifebelt. "I went back with him and gave him a second one which I had seen under my berth." Then on their second trip toward the deck, she said they met a woman who was returning to her stateroom for her jewels. She said this woman was one of the 49 people who died that day with the Mohawk. She was later found floating in the sea, and wearing her jewels.

Smith said they had to dig the lifeboats out of the snow and ice by hand, and then hoist them out on the ship’s davits. "In those days they were not lifted by machinery. By this time, we were aware that a great gash had been made in our side and the ship was beginning to list. We finally raised one lifeboat, got it down the side of the ship and started to move away. The lifeboat was filled to capacity with passengers and a few crew."

As they attempted to push the boat away from the side of the sinking liner, however, they discovered that it was still tied to the Mohawk. "A crew member started to shout for a knife to cut us away. Sam called to him to tear his coat open and pull out a gold penknife he had in his pocket. . . As it was two degrees below zero, Sam’s fingers were already frozen. The seaman found the knife, ran and cut us loose from the Mohawk.

"We rowed away as quickly as possible, and had hardly gotten at a safe distance when we witched with horror – the Mohawk sinking with 49 people aboard, many of them young. Had we not gotten away when we did, we would have been sucked in with the Mohawk as she sank."

Smith said they were picked up by the Mohawk’s sister ship, Algonquin, several hours later and taken ashore where they were met by newspaper reporters, cameras and hounded with "endless questions."

During an inquiry, it was learned that the steering system failed on the Mohawk at about 9 p.m., shortly after the ship left New York harbor, but that the crew continued on anyway, switching to a manual steering system that required communication between the bridge and the engine room. Not long afterward, a mix-up in orders from the bridge caused the engine room crew to execute a hard turn to port, running the ship at full speed directly into the path of the Talisman.

The Talisman struck the Mohawk broadside. The gash in the ship’s steel hull might not have been enough to sink it had it not been for something else that the company had done prior to the collision. Because of the depression, and in an effort to squeeze some extra revenue out of the ship, the watertight bulkheads had been opened for easier loading and unloading of cargo. With all of the bulkheads opened, the ship was doomed the moment her hull was breached.

The 387-foot-long steamer was one of four sister ships built a decade earlier for the Clyde Line. The three identical sisters were the Algonquin, Cherokee and Seminole, all names of Native American tribes in the United States.