Ghost Ship Waratah Sailed Into Oblivion In 1909

By James Donahue

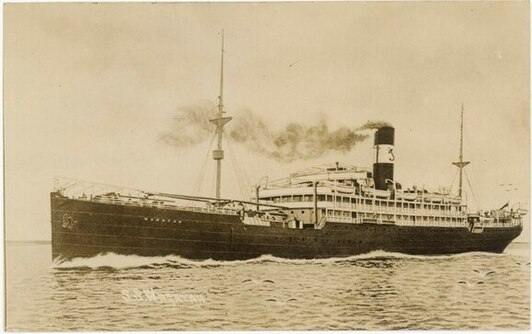

The new 500-foot-long steamship Waratah was the flagship of the Blue Anchor Line, on the second leg of its second trip from England to Australia and back, when it disappeared with its full crew and 288 passengers somewhere off the South African coast in July, 1909. No trace of this vessel has ever been found.

The Waratah, named for the emblem flower of New South Wales, Australia, was designed as a passenger and cargo liner. Her holds were designed to be used as dormitories for up to 700 immigrants making their way to Australia. On the way back the holds were converted to carry cargo. The ship was even fitted for carrying refrigerated foods. She could carry food and stores for a year at sea and even had an on-board desalination plant that could produce 5,500 gallons of fresh water a day.

Even though it was available in 1909, the Waratah’s owners did not fit the ship with the new Marconi wireless telegraph system.

The Waratah, under the command of Captain Joshua E. Ilbery, left on its maiden voyage to Australia in November, 1908, with 689 passengers in third class, and 67 first class passengers. On April 27, 1909, the vessel set out on its second and fateful trip to Melbourne. On the return trip, the steamer was bound for the South African ports of Durban and Cape Town before continuing on to England.

When the Waratah docked at Durban, one passenger, Claude Sawyer, an engineer and experienced sea traveler, left the ship. Sawyer sent a cable to his wife in London that said: “Thought Waratah top-heavy; landed Durban.” He later told the London Inquiry that he left the ship because he had visions of a man “with a long sword in a peculiar dress. He was holding the sword in his right hand and it was covered in blood.”

The Waratah steamed out of Durban on July 26 with 211 passengers and 77 crew members. The steamer was seen when it passed the Clan McIntyre the following day.

That day a severe storm developed in the area. In the midst of the gale, the liner Guelph reported passing a ship and exchanging signals by lamp, a common practice in that time. Because of the storm and poor visibility, the crew of the Guelph said they only read the last three letters of the other ship’s name as “T-A-H,” suggesting that it was the Waratah.

Later that evening the captain of the steamship Harlow reported seeing a large steamer coming up astern that he said was making so much smoke he wondered if the vessel was on fire. After it got dark, the crew of the Harlow could see the steamer’s running lights, some ten to twelve miles behind them. They said they also saw two bright flashes from the vicinity of the steamer and then the lights vanished.

The captain and mate of the Harlow later said they thought the flashes were brush fires on a nearby shore and didn’t think much of what they had seen. In fact, the incident was never entered into the ship’s log. It was only after they heard of the disappearance of Waratah that they thought the events were significant.

A board of inquiry later determined that it would have been impossible for the crews of the Harlow and the Guelph to have both seen the Waratah within that period of time. The two vessels were too far apart.

The search for the Waratah began after the steamer failed to arrive in Cape Town on July 29. It continued unsuccessfully for months and involved not only vessels from the Blue Anchor Line but three ships of the Royal Navy. Relatives of the missing passengers chartered the Wakefield in 1910 to conduct a three-month search of the area which also was unsuccessful.

That no wreckage, bodies or flotsam that might have come from the doomed steamer were ever found at sea or along the African coast made this among the greatest mysteries of the era. There has been a search for this mystery wreck that continues to this day. Among the searchers has been author Clive Cussler.

As has always happened when a ship disappears with as much publicity as the Waratah, veteran sailors in the various ports produced a long list of theories as to what happened. They include:

--The ship was carrying a cargo of 1,000 tons of lead concentrate on the trip back to England. This might have shifted in the storm causing the ship to capsize.

--A freak wave either rolled the ship or stove-in the cargo hatches, flooding the ship so quickly it caught the crew by surprise. If the ship rolled completely over, it could have trapped any debris, taking everything to the bottom with it.

--A rouge wave or the force of the storm tore away the steamer’s rudder. Without any way of contacting land, the ship and its crew was left to drift helplessly southward toward Antarctica where it was lost in either the open sea or foundered at Antarctica.

--The steamer blew up and sank so quickly no one had time to launch life boats.

--The Waratah was caught in a massive whirlpool that sucked the ship and everything on it to the bottom. No one believed a whirlpool could be large enough and powerful enough to pull down a 500-foot long steel ship, however.

--A large up-swelling of a pocket of methane gas might have reduced the density of the water and caused the ship to suddenly sink.

The very name of this steamer, Waratah, has proven to be very unlucky. The first known ship of that name sank off Ushant in 1848. Two ships named Waratah sank within months of each other off Sydney in 1887. A fourth ship with that name was lost in the Southern Ocean in 1894. There is no record of any ship bearing this name since the loss of the Blue Anchor Line steamer.

The disaster and the negative publicity that came with it literally put the Blue Anchor Line out of business. Ticket sales dropped and the company was suffering from a large financial loss from the construction and loss of the Waratah. The company liquidated in 1910.

By James Donahue

The new 500-foot-long steamship Waratah was the flagship of the Blue Anchor Line, on the second leg of its second trip from England to Australia and back, when it disappeared with its full crew and 288 passengers somewhere off the South African coast in July, 1909. No trace of this vessel has ever been found.

The Waratah, named for the emblem flower of New South Wales, Australia, was designed as a passenger and cargo liner. Her holds were designed to be used as dormitories for up to 700 immigrants making their way to Australia. On the way back the holds were converted to carry cargo. The ship was even fitted for carrying refrigerated foods. She could carry food and stores for a year at sea and even had an on-board desalination plant that could produce 5,500 gallons of fresh water a day.

Even though it was available in 1909, the Waratah’s owners did not fit the ship with the new Marconi wireless telegraph system.

The Waratah, under the command of Captain Joshua E. Ilbery, left on its maiden voyage to Australia in November, 1908, with 689 passengers in third class, and 67 first class passengers. On April 27, 1909, the vessel set out on its second and fateful trip to Melbourne. On the return trip, the steamer was bound for the South African ports of Durban and Cape Town before continuing on to England.

When the Waratah docked at Durban, one passenger, Claude Sawyer, an engineer and experienced sea traveler, left the ship. Sawyer sent a cable to his wife in London that said: “Thought Waratah top-heavy; landed Durban.” He later told the London Inquiry that he left the ship because he had visions of a man “with a long sword in a peculiar dress. He was holding the sword in his right hand and it was covered in blood.”

The Waratah steamed out of Durban on July 26 with 211 passengers and 77 crew members. The steamer was seen when it passed the Clan McIntyre the following day.

That day a severe storm developed in the area. In the midst of the gale, the liner Guelph reported passing a ship and exchanging signals by lamp, a common practice in that time. Because of the storm and poor visibility, the crew of the Guelph said they only read the last three letters of the other ship’s name as “T-A-H,” suggesting that it was the Waratah.

Later that evening the captain of the steamship Harlow reported seeing a large steamer coming up astern that he said was making so much smoke he wondered if the vessel was on fire. After it got dark, the crew of the Harlow could see the steamer’s running lights, some ten to twelve miles behind them. They said they also saw two bright flashes from the vicinity of the steamer and then the lights vanished.

The captain and mate of the Harlow later said they thought the flashes were brush fires on a nearby shore and didn’t think much of what they had seen. In fact, the incident was never entered into the ship’s log. It was only after they heard of the disappearance of Waratah that they thought the events were significant.

A board of inquiry later determined that it would have been impossible for the crews of the Harlow and the Guelph to have both seen the Waratah within that period of time. The two vessels were too far apart.

The search for the Waratah began after the steamer failed to arrive in Cape Town on July 29. It continued unsuccessfully for months and involved not only vessels from the Blue Anchor Line but three ships of the Royal Navy. Relatives of the missing passengers chartered the Wakefield in 1910 to conduct a three-month search of the area which also was unsuccessful.

That no wreckage, bodies or flotsam that might have come from the doomed steamer were ever found at sea or along the African coast made this among the greatest mysteries of the era. There has been a search for this mystery wreck that continues to this day. Among the searchers has been author Clive Cussler.

As has always happened when a ship disappears with as much publicity as the Waratah, veteran sailors in the various ports produced a long list of theories as to what happened. They include:

--The ship was carrying a cargo of 1,000 tons of lead concentrate on the trip back to England. This might have shifted in the storm causing the ship to capsize.

--A freak wave either rolled the ship or stove-in the cargo hatches, flooding the ship so quickly it caught the crew by surprise. If the ship rolled completely over, it could have trapped any debris, taking everything to the bottom with it.

--A rouge wave or the force of the storm tore away the steamer’s rudder. Without any way of contacting land, the ship and its crew was left to drift helplessly southward toward Antarctica where it was lost in either the open sea or foundered at Antarctica.

--The steamer blew up and sank so quickly no one had time to launch life boats.

--The Waratah was caught in a massive whirlpool that sucked the ship and everything on it to the bottom. No one believed a whirlpool could be large enough and powerful enough to pull down a 500-foot long steel ship, however.

--A large up-swelling of a pocket of methane gas might have reduced the density of the water and caused the ship to suddenly sink.

The very name of this steamer, Waratah, has proven to be very unlucky. The first known ship of that name sank off Ushant in 1848. Two ships named Waratah sank within months of each other off Sydney in 1887. A fourth ship with that name was lost in the Southern Ocean in 1894. There is no record of any ship bearing this name since the loss of the Blue Anchor Line steamer.

The disaster and the negative publicity that came with it literally put the Blue Anchor Line out of business. Ticket sales dropped and the company was suffering from a large financial loss from the construction and loss of the Waratah. The company liquidated in 1910.