Mrs. O'Leary's Comet

By James Donahue

Interesting how historians have a way of uncovering "new" discoveries years after they have been already discovered and forgotten.

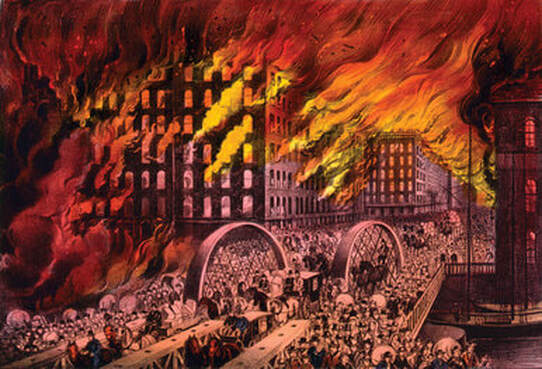

My point: the recent report in Discovery that fiery fragments of a passing rogue comet may have kindled the Great Chicago Fire and simultaneous conflagrations that ravaged forests and towns across Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan and Northern Ohio on the same week in 1871.

My book "Steaming Through Smoke And Fire 1971," an historical record of events on the Great Lakes for that year, published in 1990, addresses that theory. It was developed by author Mel Waskin in his book "Mrs. O’Learys Comet."

Waskin argued that the fire was too hot and too widespread within too short a time to be a normal blaze.

The story has been told for years about how the fire started when Mrs. O'Learys cow kicked over a kerosene lantern in a Chicago barn. That tale has never been substantiated. And it could not explain how similar fires broke out in such a wide area of the Midwest on the same day.

Survivors of the fires at both Chicago and Peshtigo, Wisconsin, told how everything got so hot that strange things happened. The iron railroad tracks at Peshtigo were bent and twisted by the heat. Attempts by fire fighters to stop the advance of flames became futile after the fire began to jump thousands of feet through the air from one part of town to another, sometimes even crossing rivers and open fields.

The Discovery story acknowledged that the comet theory has "been around," but usually discarded until Robert Wood, a retired McDonnell Douglas physicist, studied the orbital parameters of Biela's Comet.

Wood said this comet had been circling the sun every six years and nine months until it broke into large fragments in 1845 following a close encounter with Jupiter. During its next passage, astronomers noticed a 1.5-million mile, 15-day gap between the two pieces.

Wood said his analysis of the fragments positions during subsequent orbits indicated that Jupiter's gravity continued to affect their speed and trajectory, and sent the smaller piece on a path toward Earth. It ended with a fiery collision on October 8, 1871.

Wood presented his findings at a recent conference in Garden Grove, California, titled "Planetary Defense; Protecting Earth from Asteroids."

Wood told of eyewitness reports of spontaneous ignitions, "fire balloons" falling from the sky and the broad range of the fire to support his theory. He, like Waskin, suggests that the main body of the comet fell into Lake Michigan with burning fragments of it flying in all directions around the lake.

The comet debris may have consisted of frozen methane, acetylene or other combustible chemicals that exploded from the heat of entering the Earth's atmosphere.

There are some reports from that fire storm that do not support the comet theory, however. Some newspaper accounts told of fires already burning in the woods in various parts of Michigan during September and even as early as late August. Fires were sweeping the forests in northern Ohio, destroying homes and cornfields at New Haven on Oct. 5.

Fires also were said to be raging out of control in the forests of Wisconsin and even across the western prairies of Minnesota on October 4. An estimated 100 families in the northeastern counties of Wisconsin escaped to Green Bay as the fires destroyed their homes. Wild animals and even bears were seen fleeing across open fields.

There had been little rain, the summer was unusually hot and the forests were tinder.

Could it have been in that setting that Biela's Comet sent its fiery fragments crashing into Chicago and the neighboring territories?

Whatever the cause, flames blackened much of Wisconsin, swept the southern Peninsula of Michigan, and leveled the cities of Chicago, Peshtigo, Menominee, Sturgeon Bay, Holland, Big Rapids, Saginaw and many smaller communities in the three state area.

The toll in human death and destruction has never been fully realized.

By James Donahue

Interesting how historians have a way of uncovering "new" discoveries years after they have been already discovered and forgotten.

My point: the recent report in Discovery that fiery fragments of a passing rogue comet may have kindled the Great Chicago Fire and simultaneous conflagrations that ravaged forests and towns across Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan and Northern Ohio on the same week in 1871.

My book "Steaming Through Smoke And Fire 1971," an historical record of events on the Great Lakes for that year, published in 1990, addresses that theory. It was developed by author Mel Waskin in his book "Mrs. O’Learys Comet."

Waskin argued that the fire was too hot and too widespread within too short a time to be a normal blaze.

The story has been told for years about how the fire started when Mrs. O'Learys cow kicked over a kerosene lantern in a Chicago barn. That tale has never been substantiated. And it could not explain how similar fires broke out in such a wide area of the Midwest on the same day.

Survivors of the fires at both Chicago and Peshtigo, Wisconsin, told how everything got so hot that strange things happened. The iron railroad tracks at Peshtigo were bent and twisted by the heat. Attempts by fire fighters to stop the advance of flames became futile after the fire began to jump thousands of feet through the air from one part of town to another, sometimes even crossing rivers and open fields.

The Discovery story acknowledged that the comet theory has "been around," but usually discarded until Robert Wood, a retired McDonnell Douglas physicist, studied the orbital parameters of Biela's Comet.

Wood said this comet had been circling the sun every six years and nine months until it broke into large fragments in 1845 following a close encounter with Jupiter. During its next passage, astronomers noticed a 1.5-million mile, 15-day gap between the two pieces.

Wood said his analysis of the fragments positions during subsequent orbits indicated that Jupiter's gravity continued to affect their speed and trajectory, and sent the smaller piece on a path toward Earth. It ended with a fiery collision on October 8, 1871.

Wood presented his findings at a recent conference in Garden Grove, California, titled "Planetary Defense; Protecting Earth from Asteroids."

Wood told of eyewitness reports of spontaneous ignitions, "fire balloons" falling from the sky and the broad range of the fire to support his theory. He, like Waskin, suggests that the main body of the comet fell into Lake Michigan with burning fragments of it flying in all directions around the lake.

The comet debris may have consisted of frozen methane, acetylene or other combustible chemicals that exploded from the heat of entering the Earth's atmosphere.

There are some reports from that fire storm that do not support the comet theory, however. Some newspaper accounts told of fires already burning in the woods in various parts of Michigan during September and even as early as late August. Fires were sweeping the forests in northern Ohio, destroying homes and cornfields at New Haven on Oct. 5.

Fires also were said to be raging out of control in the forests of Wisconsin and even across the western prairies of Minnesota on October 4. An estimated 100 families in the northeastern counties of Wisconsin escaped to Green Bay as the fires destroyed their homes. Wild animals and even bears were seen fleeing across open fields.

There had been little rain, the summer was unusually hot and the forests were tinder.

Could it have been in that setting that Biela's Comet sent its fiery fragments crashing into Chicago and the neighboring territories?

Whatever the cause, flames blackened much of Wisconsin, swept the southern Peninsula of Michigan, and leveled the cities of Chicago, Peshtigo, Menominee, Sturgeon Bay, Holland, Big Rapids, Saginaw and many smaller communities in the three state area.

The toll in human death and destruction has never been fully realized.