The Mystery Island Of 1882

By James Donahue

There is a story allegedly documented in various newspapers of the day and in British marine records about a merchant ship that came upon a strange uncharted island in the Atlantic Ocean, and anchored there for a few days so the crew could explore it.

It was said ancient artifacts and remains of great stone buildings were found, giving credence to a theory that part of the great continent of Atlantis rose briefly from the sea before disappearing again.

Indeed, as the story is told, Captain David Robson, master of the S. S. Jesmond of British registry, carefully marked the position of the island, but it was never to be found again.

The general account of the Jesmond’s discovery goes as follows. The steamer passed through the straits of Gibraltar laden with dried fruit from Sicily bound on an westerly course for New Orleans on March 1, 1882. When in the open sea, about 200 miles west of Madeira, Robson noted in the ship’s log that the water was unusually muddy and the vessel was passing through massive shoals of dead fish. It was as if some disease or underwater volcanic blast had killed them by the millions.

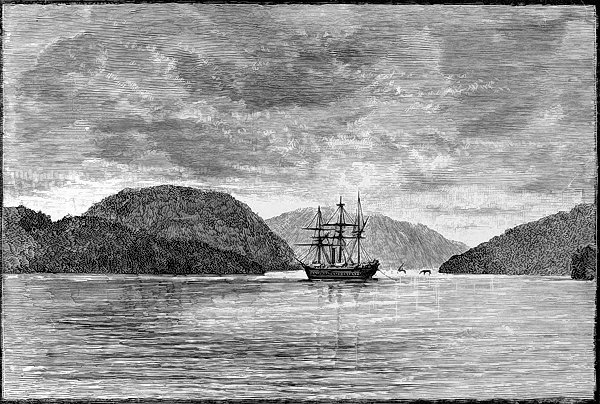

Just before arriving amid the dead and floating fish, the captain said he noticed smoke on the horizon. On the next day the shoals of dead fish seemed even thicker and the steamer came upon an island dead ahead. The smoke could be seen coming from some mountains. But Robson said no island was ever charted at this location.

When about 12 miles offshore, Robson ordered the ship’s engines stopped and dropped anchor. The anchor hit bottom at seven fathoms. Then out of curiosity, he launched a long boat and went ashore with crew members to look around.

Surprisingly, even though the island was found in warm waters about due west of the Mediterranean, Robson said he found himself on a large island with no trees or vegetation, no life of any kind, and no sandy beaches. The shore the landing party found was covered in volcanic ash.

The men hiked inland toward the mountains, but were stopped by a series of deep chasms. They returned to the beach where one sailor found a stone that appeared shaped by human involvement. This prompted Robson to send for shovels and other tools so they could dig in the gravel.

In an interview with a reporter for the Times Picayune in New Orleans, Robson said they uncovered crumbling remains of what had been massive walls. They dug for two days and found bronze swords, rings, mallets, carvings of head figures of birds and animals and two vases containing fragments of bone. They also uncovered what appeared to be a mummy enclosed in a stone case, encrusted with volcanic deposit so it was hard to distinguish from the rock. He said they actually managed to cut it free and carry it to the ship.

Reporters in New Orleans examined the artifacts on the ship. Robson said he planned to present them to a British museum. There appears to be no record of any items ever presented to a museum in England, however, and log of the Jesmond was destroyed when the building in which it was stored burned during the London blitz in 1940.

The island was never seen again.

Was it a hoax? The record shows that several other masters recorded a large area of dead floating fish on that same route at about the same time. And Captain James Newdick of the steam schooner Westbourne reported sighting the island while on route from Marselles to New York at about the same time. His report appeared in the New York Post on April 1, 1882.

By James Donahue

There is a story allegedly documented in various newspapers of the day and in British marine records about a merchant ship that came upon a strange uncharted island in the Atlantic Ocean, and anchored there for a few days so the crew could explore it.

It was said ancient artifacts and remains of great stone buildings were found, giving credence to a theory that part of the great continent of Atlantis rose briefly from the sea before disappearing again.

Indeed, as the story is told, Captain David Robson, master of the S. S. Jesmond of British registry, carefully marked the position of the island, but it was never to be found again.

The general account of the Jesmond’s discovery goes as follows. The steamer passed through the straits of Gibraltar laden with dried fruit from Sicily bound on an westerly course for New Orleans on March 1, 1882. When in the open sea, about 200 miles west of Madeira, Robson noted in the ship’s log that the water was unusually muddy and the vessel was passing through massive shoals of dead fish. It was as if some disease or underwater volcanic blast had killed them by the millions.

Just before arriving amid the dead and floating fish, the captain said he noticed smoke on the horizon. On the next day the shoals of dead fish seemed even thicker and the steamer came upon an island dead ahead. The smoke could be seen coming from some mountains. But Robson said no island was ever charted at this location.

When about 12 miles offshore, Robson ordered the ship’s engines stopped and dropped anchor. The anchor hit bottom at seven fathoms. Then out of curiosity, he launched a long boat and went ashore with crew members to look around.

Surprisingly, even though the island was found in warm waters about due west of the Mediterranean, Robson said he found himself on a large island with no trees or vegetation, no life of any kind, and no sandy beaches. The shore the landing party found was covered in volcanic ash.

The men hiked inland toward the mountains, but were stopped by a series of deep chasms. They returned to the beach where one sailor found a stone that appeared shaped by human involvement. This prompted Robson to send for shovels and other tools so they could dig in the gravel.

In an interview with a reporter for the Times Picayune in New Orleans, Robson said they uncovered crumbling remains of what had been massive walls. They dug for two days and found bronze swords, rings, mallets, carvings of head figures of birds and animals and two vases containing fragments of bone. They also uncovered what appeared to be a mummy enclosed in a stone case, encrusted with volcanic deposit so it was hard to distinguish from the rock. He said they actually managed to cut it free and carry it to the ship.

Reporters in New Orleans examined the artifacts on the ship. Robson said he planned to present them to a British museum. There appears to be no record of any items ever presented to a museum in England, however, and log of the Jesmond was destroyed when the building in which it was stored burned during the London blitz in 1940.

The island was never seen again.

Was it a hoax? The record shows that several other masters recorded a large area of dead floating fish on that same route at about the same time. And Captain James Newdick of the steam schooner Westbourne reported sighting the island while on route from Marselles to New York at about the same time. His report appeared in the New York Post on April 1, 1882.