Duchess of Atholl Sunk By German Torpedo

By James Donahue

Among the many ships lost during World War II was the liner Duchess of Atholl, sunk by a spray of torpedoes from a German U-Boat off the coast of Africa in October, 1942. The liner was serving as a troop ship for allied forces at the time.

Those were the early years of the war when the skippers of the German submarines were still fighting a gentleman’s war. Survivor Charles Cusack said the ship sank slowly, giving the crew time to launch the lifeboats and stand off to watch the vessel go down by the stern.

Cusack wrote: “After she had gone the U-boat surfaced and an officer emerged on the conning tower with a megaphone. He apologized for sinking her and asked if we needed any assistance, medical or otherwise. He said that he had sent an S.O.S. and for us to keep all boats together and for us not to drift apart because it would be a couple of days before help would arrive. He then went down into the sub and she then submerged, leaving us all alone in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.”

The master of that submarine, identified as U178, was Kapitan Hans Ibbeken. That submarine successfully completed three patrols during the war, sinking 13 allied ships and damaging another. Ibbeken was the first of three commanders.

Cusack said the sailors spent three terrible days in the hot equatorial sun waiting for rescue. The steamer was sunk near the equator so the weather was hot and steamy and everybody suffered from sunburn and sun stroke.

What he didn’t mention, probably because of wartime censorship, was that the Duchess of Atholl was carrying 831 people at the time it was sunk. That included the ship’s own crew of 296, 12 crew members from the Princess Marguerite that was sunk earlier, and 37 survivors from the S.S.Gazeon. Among the passengers were 58 women and 34 children. Thus there were a lot of people packed in those lifeboats for three long days in the middle of the open sea.

Cusack said the ship had been carrying a cargo of oranges, and many of them floated to the surface, so everybody had oranges to eat and suck on, which helped them survive.

He wrote: “During the day it was so very hot, with the sun blazing down on us. One middle aged man, the pastry chef who worked in the bakery, caught sunstroke and was in bad shape. He was rambling and one of his eyeballs had rolled back, just revealing the white of his eye. It was frightening. We called the motor launch over and somehow managed to transfer him over to the ship’s doctor.

“The nighttime was just as bad. No one could sleep with the motion of the boat in the Atlantic waves. In fact, most of us were seasick from the motion and very wet with the spray. By the time we were picked up we were all pretty exhausted.”

The survivors were rescued by the British boarding ship Corinthian. Cusack said the ship circled the boats a few times, looking for signs that the U-boat was still in the area. Then it pulled up with nets over her sides so the people could climb up its sides. Some of the people were too weak and had to be helped.

The Dutchess of Atholl was steaming without escort from Cape Town, South Africa, to Glasgow, Scotland, when it was lost. Cusack said the first torpedo struck at about 6 a.m. while most of the crew members were still in their bunks. “It was strange and frightening. All engineering generators stopped and all lights went out. There were cries of ‘we’ve been hit” and the dreaded word, “torpedoes.” Then Captain Arthur Henry Allinson Moore gave orders to abandon ship.

Five died in the attack. Four of them were in the engine room which was hit by the first torpedo.

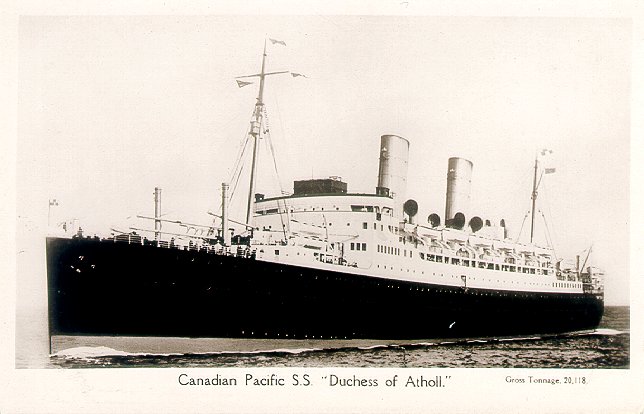

The Duchess of Atholl was launched at Glasgow in 1927 and made its maiden voyage in July, 1928. The liner briefly held the record for an eastbound Atlantic crossing from Canada to Liverpool at six days and 13 hours.

The vessel remained in service for the Canadian Pacific North Atlantic until 1940 when it joined the other lines of that era as a troopship in the war effort.

By James Donahue

Among the many ships lost during World War II was the liner Duchess of Atholl, sunk by a spray of torpedoes from a German U-Boat off the coast of Africa in October, 1942. The liner was serving as a troop ship for allied forces at the time.

Those were the early years of the war when the skippers of the German submarines were still fighting a gentleman’s war. Survivor Charles Cusack said the ship sank slowly, giving the crew time to launch the lifeboats and stand off to watch the vessel go down by the stern.

Cusack wrote: “After she had gone the U-boat surfaced and an officer emerged on the conning tower with a megaphone. He apologized for sinking her and asked if we needed any assistance, medical or otherwise. He said that he had sent an S.O.S. and for us to keep all boats together and for us not to drift apart because it would be a couple of days before help would arrive. He then went down into the sub and she then submerged, leaving us all alone in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.”

The master of that submarine, identified as U178, was Kapitan Hans Ibbeken. That submarine successfully completed three patrols during the war, sinking 13 allied ships and damaging another. Ibbeken was the first of three commanders.

Cusack said the sailors spent three terrible days in the hot equatorial sun waiting for rescue. The steamer was sunk near the equator so the weather was hot and steamy and everybody suffered from sunburn and sun stroke.

What he didn’t mention, probably because of wartime censorship, was that the Duchess of Atholl was carrying 831 people at the time it was sunk. That included the ship’s own crew of 296, 12 crew members from the Princess Marguerite that was sunk earlier, and 37 survivors from the S.S.Gazeon. Among the passengers were 58 women and 34 children. Thus there were a lot of people packed in those lifeboats for three long days in the middle of the open sea.

Cusack said the ship had been carrying a cargo of oranges, and many of them floated to the surface, so everybody had oranges to eat and suck on, which helped them survive.

He wrote: “During the day it was so very hot, with the sun blazing down on us. One middle aged man, the pastry chef who worked in the bakery, caught sunstroke and was in bad shape. He was rambling and one of his eyeballs had rolled back, just revealing the white of his eye. It was frightening. We called the motor launch over and somehow managed to transfer him over to the ship’s doctor.

“The nighttime was just as bad. No one could sleep with the motion of the boat in the Atlantic waves. In fact, most of us were seasick from the motion and very wet with the spray. By the time we were picked up we were all pretty exhausted.”

The survivors were rescued by the British boarding ship Corinthian. Cusack said the ship circled the boats a few times, looking for signs that the U-boat was still in the area. Then it pulled up with nets over her sides so the people could climb up its sides. Some of the people were too weak and had to be helped.

The Dutchess of Atholl was steaming without escort from Cape Town, South Africa, to Glasgow, Scotland, when it was lost. Cusack said the first torpedo struck at about 6 a.m. while most of the crew members were still in their bunks. “It was strange and frightening. All engineering generators stopped and all lights went out. There were cries of ‘we’ve been hit” and the dreaded word, “torpedoes.” Then Captain Arthur Henry Allinson Moore gave orders to abandon ship.

Five died in the attack. Four of them were in the engine room which was hit by the first torpedo.

The Duchess of Atholl was launched at Glasgow in 1927 and made its maiden voyage in July, 1928. The liner briefly held the record for an eastbound Atlantic crossing from Canada to Liverpool at six days and 13 hours.

The vessel remained in service for the Canadian Pacific North Atlantic until 1940 when it joined the other lines of that era as a troopship in the war effort.