Memories Of My Early Childhood

By James Donahue

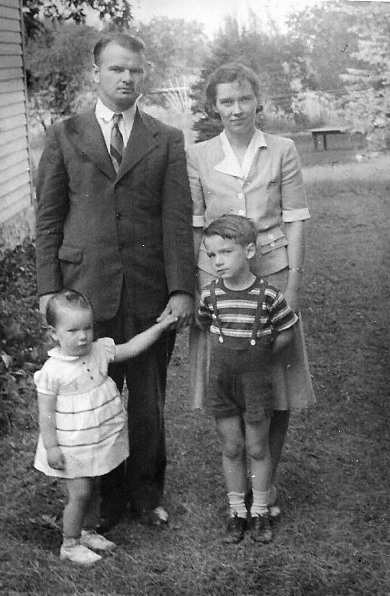

I have recollections of a time before the world was at war and people were still living under the shadow of the Great Depression. As children, we thought little about the effects of poverty. While I was luckier than most, there was an awareness that my playmates in the neighborhood sometimes went without a good meal, wore old worn tennis shoes with holes in the bottom and dungarees with knees so bare their mothers sewed patches there.

My parents, who somehow had clawed their way out of the terrible financial hole created by the depression years, provided me and my siblings a modest home in a small, Midwestern community along the shore of Lake Huron. Dad had worked long hours painting barns, picking fruit and doing other farm labor for a dollar a day to pay his way through college. By the time I arrived he was employed as a chemical engineer at the Huron Milling Company, the main employer in Harbor Beach. Consequently we always had food on our table. A box of new clothes, coats and shoes from the Sears Roebuck catalog arrived late each summer so we had new things to wear to school.

While we were never classified as well-to-do, we lived in a town where many families were overwhelmed by poverty. I didn’t know her then, but not many miles away, my future wife, Doris, was one of those depression-strapped families. She told of wearing hand-sewn dresses made from burlap feed sacks to school, of not having shoes to wear until the snow was flying, and waiting with her mother and brothers for the lights of her father’s car coming down the road at night, hoping he was bringing something for them to eat.

That was how people in Michigan were living during the years just before and during World War II. Those of us old enough to remember it, know how it is to survive a depression and struggle through extreme poverty. It has an effect on people that never goes away.

Even though my parents never went without once my father landed that job, they always lived a frugal life style. That was how the depression affected them. I remember my mother carefully reading the grocery ads in the town's weekly paper, then traveling between the three grocery stores in town, carefully picking out the sale-priced items. Sometimes she would drive blocks to save a nickel on a box of laundry soap. I used to wonder if she ever thought about the cost of the gasoline burned to make the trip.

My mother grew up with a family of four children on a farm on the Western side of Michigan. Her father ruined his lungs driving a truck and hauling lime to bring home the bacon and keep his family going. He also was a chain smoker. He eventually died of emphysema.

My father was the second youngest in a family of nine children who grew up in Kansas. They lived at a time when travel amounted to a thumb up along the highway, and two or more children shared the same bed.

Even after he was financially secure, my father drove his cars until they literally fell apart under him. I recall one final trip to an automobile dealership in which our old car chugged to a final stop in front of the dealership and would run no more. We were forced to buy another vehicle before we could go back home. It was usually always a used car. I remember only one new car that he ever bought. It was a modest white Ford sedan without any frills.

I grew up in a different era, one that became even more difficult after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and plunged the United States into World War II. There is a belief among many people that the war brought an end to the depression, but that is not true. Indeed, it put a lot of people to work. The men went off to war and the women took their place in the nation’s factories building the machines of war. But life at home became worse than ever. Most commodities needed for the war effort were either made unavailable or were so severely rationed that when we got them, it was either a treat or purchased on the black market at a high price.

The other problem was that many foods and materials imported from other nations became impossible to acquire during the war. Sugar was so rare we were forced to use a super condensed form of milk on our morning cereal that gave it a sweet taste. Gasoline was rationed so we couldn’t go anywhere, and rubber tires were almost impossible to buy. They hadn’t yet invented synthetic rubber to make good tires.

Women went without silk stockings during the war. But inventive minds in the nation’s laboratories produced nylon which could be threaded like silk, and the nylon was in vogue. From this came Rayon, then better plastics, and a whole new industry evolved from the war effort.

By the time the war ended in 1945, America was poised to crank up its factories and put people back to work filling the need for housing, new automobiles, and all of the things we went without during the war. That was when the depression officially ended.

It wasn’t until I recently got my hands on my late father’s memoirs that I realized just how much the world has changed since the days of my own childhood. Dad was pursuing his dream to be a chemist and was working on an advanced degree by teaching chemistry at Michigan State College in Lansing when he met my mother. He hitch hiked his way over a maze of undeveloped dirt roads to Harbor Beach to apply for a job with the old Huron Milling Company which was then operating in that town. He had to get a job before he and mom could afford to get married.

That job paid $140 a month, which apparently was a very good salary at the time. Dad mentioned that they paid rent of $25 a month on our house on South Huron Avenue. It was not long after they arrived in Harbor Beach that they bought their first car, a 1936 Chevrolet, which they drove all through the war years.

My memories of that home, and that time, are all happy ones. I grew up with a lot of children in the neighborhood. That was a time when people didn’t worry about pedophilia or children going missing, so we had a free run of not only the neighborhood, but a wonderful wooded area and a golf course that wrapped itself around the neighborhood. It was an amazing playground filled with trees, open fields, hills, and even a little stream filled with frogs and other creatures just waiting for our curious hands to find them.

The only danger was the golfers who played the course during the summer months. There was always a chance of getting hit in the head by a flying ball if we dashed across the fairway at the wrong time. An even bigger danger was being chased off the grounds by the greens keepers or the course manager for getting in the way of golfers. We discovered that the golfers were always losing balls in the deep grass and wooded areas surrounding the course. It was great sport for us to find those lost balls and sell them back to the golfers. During the late fall, winter and early spring that golf course was our playground. The hills were perfect places to sled during the snows of winter.

Best of all, at least for me, was the fact that the Pere Marquette freight train, pulled by a steam engine, arrived in town every afternoon at around five o’clock. The train followed a track that ran alongside the golf course and into the factory grounds in the heart of town where my father worked. I could see it clearly from my upstairs bedroom window, or, if I could get out of the house in time, I could race through the woods and then run across the golf course in time to watch the train from a closer vantage point. It was great when I waved at the engineer and got him to wave back.

That old house on South Huron Avenue was an ample two-story, four-bedroom structure with a large bathroom with a claw-foot tub on the second floor. It had hot water radiators with a coal-fired boiler in the basement. We had to order a coal truck to dump loads of dirty black coal through one of the basement windows into a special room designed just to hold the coal in the basement, right next to the boiler.

That boiler room, located right at the foot of the concrete steps leading into the basement, was a spooky place in the winter when the furnace was being used. Beyond that was the laundry room where my mother washed our clothes in an old fashioned tub that had a hand-operated ringer attached to the side. Before the clothes were carried outside and hung on laundry lines to dry, mother ran them through the ringer, forcing most of the water out.

My father kept a large garden on the property, which stretched back behind a single-car garage, across a vacant space and through an orchard. Mom canned the fruit from the orchard and the vegetables from the garden. The canned food was kept on shelves in yet another basement room located off the laundry room.

The other thing I liked about that property was that there was a long, slanted-roofed barn on the north side of the site. We found a way to scale a tree behind that barn and get to the roof, which was a great place to hang out. Dad also built a playhouse in that orchard, and had a load of sand dumped beside it, which also became a popular hangout for all neighborhood children. He installed a swing in the yard, so we never lacked for things to do in outdoor play.

I was especially fond of an old rowboat left rotting in the tall grass beside the grape arbor located behind the garage. That boat became an imaginary ship from which many an adventure occurred. It also became a stage coach, fortress, and just about anything we wanted it to be in our daily play.

Indeed, that house on South Huron Avenue was the perfect place for a child to grow up. I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

By James Donahue

I have recollections of a time before the world was at war and people were still living under the shadow of the Great Depression. As children, we thought little about the effects of poverty. While I was luckier than most, there was an awareness that my playmates in the neighborhood sometimes went without a good meal, wore old worn tennis shoes with holes in the bottom and dungarees with knees so bare their mothers sewed patches there.

My parents, who somehow had clawed their way out of the terrible financial hole created by the depression years, provided me and my siblings a modest home in a small, Midwestern community along the shore of Lake Huron. Dad had worked long hours painting barns, picking fruit and doing other farm labor for a dollar a day to pay his way through college. By the time I arrived he was employed as a chemical engineer at the Huron Milling Company, the main employer in Harbor Beach. Consequently we always had food on our table. A box of new clothes, coats and shoes from the Sears Roebuck catalog arrived late each summer so we had new things to wear to school.

While we were never classified as well-to-do, we lived in a town where many families were overwhelmed by poverty. I didn’t know her then, but not many miles away, my future wife, Doris, was one of those depression-strapped families. She told of wearing hand-sewn dresses made from burlap feed sacks to school, of not having shoes to wear until the snow was flying, and waiting with her mother and brothers for the lights of her father’s car coming down the road at night, hoping he was bringing something for them to eat.

That was how people in Michigan were living during the years just before and during World War II. Those of us old enough to remember it, know how it is to survive a depression and struggle through extreme poverty. It has an effect on people that never goes away.

Even though my parents never went without once my father landed that job, they always lived a frugal life style. That was how the depression affected them. I remember my mother carefully reading the grocery ads in the town's weekly paper, then traveling between the three grocery stores in town, carefully picking out the sale-priced items. Sometimes she would drive blocks to save a nickel on a box of laundry soap. I used to wonder if she ever thought about the cost of the gasoline burned to make the trip.

My mother grew up with a family of four children on a farm on the Western side of Michigan. Her father ruined his lungs driving a truck and hauling lime to bring home the bacon and keep his family going. He also was a chain smoker. He eventually died of emphysema.

My father was the second youngest in a family of nine children who grew up in Kansas. They lived at a time when travel amounted to a thumb up along the highway, and two or more children shared the same bed.

Even after he was financially secure, my father drove his cars until they literally fell apart under him. I recall one final trip to an automobile dealership in which our old car chugged to a final stop in front of the dealership and would run no more. We were forced to buy another vehicle before we could go back home. It was usually always a used car. I remember only one new car that he ever bought. It was a modest white Ford sedan without any frills.

I grew up in a different era, one that became even more difficult after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and plunged the United States into World War II. There is a belief among many people that the war brought an end to the depression, but that is not true. Indeed, it put a lot of people to work. The men went off to war and the women took their place in the nation’s factories building the machines of war. But life at home became worse than ever. Most commodities needed for the war effort were either made unavailable or were so severely rationed that when we got them, it was either a treat or purchased on the black market at a high price.

The other problem was that many foods and materials imported from other nations became impossible to acquire during the war. Sugar was so rare we were forced to use a super condensed form of milk on our morning cereal that gave it a sweet taste. Gasoline was rationed so we couldn’t go anywhere, and rubber tires were almost impossible to buy. They hadn’t yet invented synthetic rubber to make good tires.

Women went without silk stockings during the war. But inventive minds in the nation’s laboratories produced nylon which could be threaded like silk, and the nylon was in vogue. From this came Rayon, then better plastics, and a whole new industry evolved from the war effort.

By the time the war ended in 1945, America was poised to crank up its factories and put people back to work filling the need for housing, new automobiles, and all of the things we went without during the war. That was when the depression officially ended.

It wasn’t until I recently got my hands on my late father’s memoirs that I realized just how much the world has changed since the days of my own childhood. Dad was pursuing his dream to be a chemist and was working on an advanced degree by teaching chemistry at Michigan State College in Lansing when he met my mother. He hitch hiked his way over a maze of undeveloped dirt roads to Harbor Beach to apply for a job with the old Huron Milling Company which was then operating in that town. He had to get a job before he and mom could afford to get married.

That job paid $140 a month, which apparently was a very good salary at the time. Dad mentioned that they paid rent of $25 a month on our house on South Huron Avenue. It was not long after they arrived in Harbor Beach that they bought their first car, a 1936 Chevrolet, which they drove all through the war years.

My memories of that home, and that time, are all happy ones. I grew up with a lot of children in the neighborhood. That was a time when people didn’t worry about pedophilia or children going missing, so we had a free run of not only the neighborhood, but a wonderful wooded area and a golf course that wrapped itself around the neighborhood. It was an amazing playground filled with trees, open fields, hills, and even a little stream filled with frogs and other creatures just waiting for our curious hands to find them.

The only danger was the golfers who played the course during the summer months. There was always a chance of getting hit in the head by a flying ball if we dashed across the fairway at the wrong time. An even bigger danger was being chased off the grounds by the greens keepers or the course manager for getting in the way of golfers. We discovered that the golfers were always losing balls in the deep grass and wooded areas surrounding the course. It was great sport for us to find those lost balls and sell them back to the golfers. During the late fall, winter and early spring that golf course was our playground. The hills were perfect places to sled during the snows of winter.

Best of all, at least for me, was the fact that the Pere Marquette freight train, pulled by a steam engine, arrived in town every afternoon at around five o’clock. The train followed a track that ran alongside the golf course and into the factory grounds in the heart of town where my father worked. I could see it clearly from my upstairs bedroom window, or, if I could get out of the house in time, I could race through the woods and then run across the golf course in time to watch the train from a closer vantage point. It was great when I waved at the engineer and got him to wave back.

That old house on South Huron Avenue was an ample two-story, four-bedroom structure with a large bathroom with a claw-foot tub on the second floor. It had hot water radiators with a coal-fired boiler in the basement. We had to order a coal truck to dump loads of dirty black coal through one of the basement windows into a special room designed just to hold the coal in the basement, right next to the boiler.

That boiler room, located right at the foot of the concrete steps leading into the basement, was a spooky place in the winter when the furnace was being used. Beyond that was the laundry room where my mother washed our clothes in an old fashioned tub that had a hand-operated ringer attached to the side. Before the clothes were carried outside and hung on laundry lines to dry, mother ran them through the ringer, forcing most of the water out.

My father kept a large garden on the property, which stretched back behind a single-car garage, across a vacant space and through an orchard. Mom canned the fruit from the orchard and the vegetables from the garden. The canned food was kept on shelves in yet another basement room located off the laundry room.

The other thing I liked about that property was that there was a long, slanted-roofed barn on the north side of the site. We found a way to scale a tree behind that barn and get to the roof, which was a great place to hang out. Dad also built a playhouse in that orchard, and had a load of sand dumped beside it, which also became a popular hangout for all neighborhood children. He installed a swing in the yard, so we never lacked for things to do in outdoor play.

I was especially fond of an old rowboat left rotting in the tall grass beside the grape arbor located behind the garage. That boat became an imaginary ship from which many an adventure occurred. It also became a stage coach, fortress, and just about anything we wanted it to be in our daily play.

Indeed, that house on South Huron Avenue was the perfect place for a child to grow up. I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.