Fire On The E. K. Collins

By James Donahue

Canadian furniture-store operator William Bartlett never expected to be a hero. Even Bartlett had to admit that he just happened to be at the right place at the right time, and have a boat available when it was really needed.

An estimated seventy passengers and crew members on the burning steamer E. K. Collins needed all the help they could get on the night of Sunday, October 8, 1854. As the fire engulfed the ship, destroying even the lifeboats, the people had no place to go but over the side and into the cold moving waters of the Detroit River. Twenty-one souls perished in the fire, but it could have been much worse.

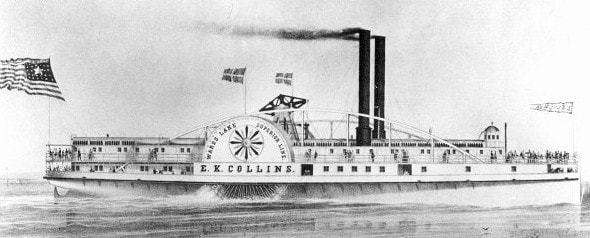

The handsome, two-year-old Ward Line steamer was the pride of the fleet in 1854. Built by the well-known Marne City, Michigan shipbuilder John Bushnell, the Collins measured two hundred fifty-nine feet in length and was lavishly furnished to draw passengers on a route that took the ship between Sault Ste. Marie and Buffalo.

The Collins, commanded by Capt. H. J. Jones of Detroit, was on her way down the Detroit River on the night of the fire. She laid over briefly at Detroit to take on freight and passengers, then cast off for a night trip to Lake Erie and on to Cleveland. It was a calm night but there was an autumn nip in the air so most of the passengers were hanging out in the ship’s lounge. Many retired to their staterooms after supper.

Jones remained in the pilot house all evening, piloting the ship through the narrow waters of Lime-Kiln Crossing. He was breathing easier now that the lights of Malden, Ontario, the old name for Amherstburg, were in sight. Soon the ship would enter the open waters of Lake Erie.

The fire broke out somewhere on the boiler deck, just aft of the engine room, at around 8:00 PM. Some thought it might have started from a carelessly tossed ash from a smoker’s pipe. Nobody ever knew for sure. The flames spread with terrible speed. The alarm was sounded, but before the crew got the hoses rolled out, the fire reached the engine room where the pumps were located. The engineer and fireman fled the flames without ever starting the pumps. Within minutes the steam was too low to keep the big paddle wheels turning, and the ship became a drifting, burning hulk filled with very frightened people.

All was bedlam as the fire raced through the ship’s superstructure. The lifeboats caught fire so they could not be used. Women screamed. People ran ahead of the advancing flames to the bow of the ship while others leaped over the side and into the water.

Bartlett was one of several spectators on the streets of Malden who watched in horror as the burning vessel floated past their town. He realized that there were people on board who needed help, and he ran to the dock where his personal boat was tied.

Bartlett found fourteen people hanging on the ship’s anchor chain while the fire burned the deck just over their heads. He took them into his boat then started around the blazing hull looking for others. Five more were found clinging to the paddles on the port wheel, and six others were on the starboard wheel. Two more were pulled from the water. Before it was over, Bartlett was credited with rescuing twenty-seven of the forty-four survivors of the burning Collins.

Others were rescued by the propeller Fintry, which pulled alongside the drifting Collins so people could jump to the Fintry’s deck. Captain Langley, the Fintry’s master, risked setting fire to his own command to save lives. A few other small boats also came out from Malden and still more people were pulled from the water before they drowned.

The hull of the burned-out Collins drifted downstream until it went aground in Callam’s Bay. It was towed back to Detroit where it was rebuilt as a steam barge. She was enrolled as a new vessel in 1857 and given a new name: Ark. Nine years later the Ark foundered with all hands during an October gale on Lake Huron. But that is another story.

By James Donahue

Canadian furniture-store operator William Bartlett never expected to be a hero. Even Bartlett had to admit that he just happened to be at the right place at the right time, and have a boat available when it was really needed.

An estimated seventy passengers and crew members on the burning steamer E. K. Collins needed all the help they could get on the night of Sunday, October 8, 1854. As the fire engulfed the ship, destroying even the lifeboats, the people had no place to go but over the side and into the cold moving waters of the Detroit River. Twenty-one souls perished in the fire, but it could have been much worse.

The handsome, two-year-old Ward Line steamer was the pride of the fleet in 1854. Built by the well-known Marne City, Michigan shipbuilder John Bushnell, the Collins measured two hundred fifty-nine feet in length and was lavishly furnished to draw passengers on a route that took the ship between Sault Ste. Marie and Buffalo.

The Collins, commanded by Capt. H. J. Jones of Detroit, was on her way down the Detroit River on the night of the fire. She laid over briefly at Detroit to take on freight and passengers, then cast off for a night trip to Lake Erie and on to Cleveland. It was a calm night but there was an autumn nip in the air so most of the passengers were hanging out in the ship’s lounge. Many retired to their staterooms after supper.

Jones remained in the pilot house all evening, piloting the ship through the narrow waters of Lime-Kiln Crossing. He was breathing easier now that the lights of Malden, Ontario, the old name for Amherstburg, were in sight. Soon the ship would enter the open waters of Lake Erie.

The fire broke out somewhere on the boiler deck, just aft of the engine room, at around 8:00 PM. Some thought it might have started from a carelessly tossed ash from a smoker’s pipe. Nobody ever knew for sure. The flames spread with terrible speed. The alarm was sounded, but before the crew got the hoses rolled out, the fire reached the engine room where the pumps were located. The engineer and fireman fled the flames without ever starting the pumps. Within minutes the steam was too low to keep the big paddle wheels turning, and the ship became a drifting, burning hulk filled with very frightened people.

All was bedlam as the fire raced through the ship’s superstructure. The lifeboats caught fire so they could not be used. Women screamed. People ran ahead of the advancing flames to the bow of the ship while others leaped over the side and into the water.

Bartlett was one of several spectators on the streets of Malden who watched in horror as the burning vessel floated past their town. He realized that there were people on board who needed help, and he ran to the dock where his personal boat was tied.

Bartlett found fourteen people hanging on the ship’s anchor chain while the fire burned the deck just over their heads. He took them into his boat then started around the blazing hull looking for others. Five more were found clinging to the paddles on the port wheel, and six others were on the starboard wheel. Two more were pulled from the water. Before it was over, Bartlett was credited with rescuing twenty-seven of the forty-four survivors of the burning Collins.

Others were rescued by the propeller Fintry, which pulled alongside the drifting Collins so people could jump to the Fintry’s deck. Captain Langley, the Fintry’s master, risked setting fire to his own command to save lives. A few other small boats also came out from Malden and still more people were pulled from the water before they drowned.

The hull of the burned-out Collins drifted downstream until it went aground in Callam’s Bay. It was towed back to Detroit where it was rebuilt as a steam barge. She was enrolled as a new vessel in 1857 and given a new name: Ark. Nine years later the Ark foundered with all hands during an October gale on Lake Huron. But that is another story.