The Real American Thanksgiving Story

By James Donahue

Our schools appear to still be filling the heads of American children with that age-old twisted story of the first thanksgiving when the Pilgrims in 1621 sat down with the Wampanoag Confederation of natives to share in the fruits of their first year of harvest.

That part of the story is true. But it is surrounded by a larger history of barbaric brutality and native reprisals that marked a dark and carefully covered-over part of the history of the American settlements. While the Puritans sought religious freedom when they arrived in the New World, it wasn’t freedom from persecution in Europe as history books have been teaching.

An essay on the subject by historian Chuck Larsen, on a web site for the Manataka American Indian Council, identified the Puritans as a radical religious group that believed they were living in the “end times” and that they were the “chosen elect” as described in the Book of the Revelation. They saw themselves as establishing an apocalyptic “new world” in the wilds of New England and were willing to use “ any means, including deceptions, treachery, torture, war and genocide to achieve that end. They saw themselves as fighting a holy war against Satan, and everyone who disagreed with them was the enemy.”

Larsen wrote that his research reveals that “the Wampanoag Indians were not the ‘friendly savages’ some of us were told about when we were in the primary grades. Nor were they invited out of the goodness of the Pilgrims’ hearts to share the fruits of the Pilgrims’ harvest in a demonstration of Christian charity and interracial brotherhood.”

Indeed, the Puritans regarded the natives as evil tools of Satan, but were caught up in an odd situation that first year after landing at Plymouth Rock when one specific member of the Patuxet tribe, known among the whites as Squanto, helped them produce a successful planting of corn and other crops, and taught them where to fish and capture eels for food.

There is irony in the Squanto story. He was among a number of natives captured by an English expedition headed by Thomas Hunt in 1614, and carried on a ship to Spain where he was sold into slavery. Some Catholic friars rescued Squanto, converted him to Christianity, and brought him to England. There Squanto worked briefly at ship building before finding a vessel that took him back to his native homeland. He arrived in 1619, one year before the Mayflower landed.

Perhaps it was Squanto’s conversion to the Christian faith, or his personal friendship with a British explorer named John Weymouth, that led him to help the Pilgrims survive their first year in that fledgling colony that became the community of Plymouth. The Pilgrims, however, saw Squanto as “merely an instrument of God, set in the wilderness to provide for the survival of His chosen people.”

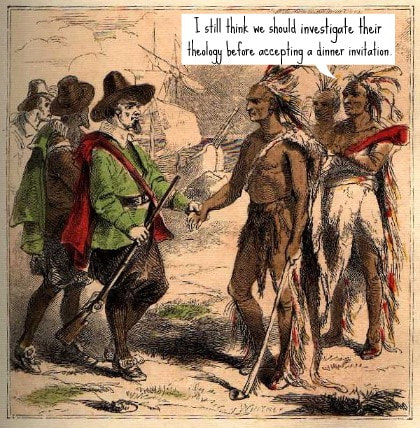

It was through Squanto’s efforts that a peace treaty was brokered between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag Confederation of tribes. Larsen wrote that the real reason the Wampanoag tribal leaders were present during that first historic “thanksgiving” feast was to sign a treaty that would secure the lands of the Plymouth Plantation for the Pilgrims.

“It should also be noted that the Indians, possibly out of a sense of charity toward their hosts, ended up bringing the majority of the food to the feast,” Larsen wrote.

That was one moment of a strained cooperative feast shared by people separated by a radical religious bigotry that has never ever been erased. What happened after that was such a cruel display of wickedness that American historians have tended to sweep it all under a rug and pretend it did not happen.

While the Puritans considered the natives barbarians and had no problem capturing them and selling them into slavery in Europe, they were joined by British and Dutch settlers who set about seizing the native territorial lands for farming, hunting and trapping animals for a fur trade and engaging in armed warfare with the tribes.

Larsen wrote that “a generation later, after the balance of power had indeed shifted, the Indian and white children of that Thanksgiving were striving to kill each other in the genocidal conflict known as King Philip’s War. At the end of that conflict most of the New England Indians were either exterminated or refugees among the French in Canada, or they were sold into slavery in the Carolina's by the Puritans.”

When we examine all of the facts, that first so-called “thanksgiving feast” at the Plymouth Colony as not a celebration of the harvest or even a recognition of gratitude for the help the natives gave to the Pilgrims.

It was not until President George Washington proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving on October 3, 1789, that the first real celebration known as Thanksgiving was held. President John Adams declared two additional celebrations of thanksgiving in 1798 and 1799. It was not until Abraham Lincoln declared it an annual holiday in 1863 that the concept of Thanksgiving as we currently know it was born.

By James Donahue

Our schools appear to still be filling the heads of American children with that age-old twisted story of the first thanksgiving when the Pilgrims in 1621 sat down with the Wampanoag Confederation of natives to share in the fruits of their first year of harvest.

That part of the story is true. But it is surrounded by a larger history of barbaric brutality and native reprisals that marked a dark and carefully covered-over part of the history of the American settlements. While the Puritans sought religious freedom when they arrived in the New World, it wasn’t freedom from persecution in Europe as history books have been teaching.

An essay on the subject by historian Chuck Larsen, on a web site for the Manataka American Indian Council, identified the Puritans as a radical religious group that believed they were living in the “end times” and that they were the “chosen elect” as described in the Book of the Revelation. They saw themselves as establishing an apocalyptic “new world” in the wilds of New England and were willing to use “ any means, including deceptions, treachery, torture, war and genocide to achieve that end. They saw themselves as fighting a holy war against Satan, and everyone who disagreed with them was the enemy.”

Larsen wrote that his research reveals that “the Wampanoag Indians were not the ‘friendly savages’ some of us were told about when we were in the primary grades. Nor were they invited out of the goodness of the Pilgrims’ hearts to share the fruits of the Pilgrims’ harvest in a demonstration of Christian charity and interracial brotherhood.”

Indeed, the Puritans regarded the natives as evil tools of Satan, but were caught up in an odd situation that first year after landing at Plymouth Rock when one specific member of the Patuxet tribe, known among the whites as Squanto, helped them produce a successful planting of corn and other crops, and taught them where to fish and capture eels for food.

There is irony in the Squanto story. He was among a number of natives captured by an English expedition headed by Thomas Hunt in 1614, and carried on a ship to Spain where he was sold into slavery. Some Catholic friars rescued Squanto, converted him to Christianity, and brought him to England. There Squanto worked briefly at ship building before finding a vessel that took him back to his native homeland. He arrived in 1619, one year before the Mayflower landed.

Perhaps it was Squanto’s conversion to the Christian faith, or his personal friendship with a British explorer named John Weymouth, that led him to help the Pilgrims survive their first year in that fledgling colony that became the community of Plymouth. The Pilgrims, however, saw Squanto as “merely an instrument of God, set in the wilderness to provide for the survival of His chosen people.”

It was through Squanto’s efforts that a peace treaty was brokered between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag Confederation of tribes. Larsen wrote that the real reason the Wampanoag tribal leaders were present during that first historic “thanksgiving” feast was to sign a treaty that would secure the lands of the Plymouth Plantation for the Pilgrims.

“It should also be noted that the Indians, possibly out of a sense of charity toward their hosts, ended up bringing the majority of the food to the feast,” Larsen wrote.

That was one moment of a strained cooperative feast shared by people separated by a radical religious bigotry that has never ever been erased. What happened after that was such a cruel display of wickedness that American historians have tended to sweep it all under a rug and pretend it did not happen.

While the Puritans considered the natives barbarians and had no problem capturing them and selling them into slavery in Europe, they were joined by British and Dutch settlers who set about seizing the native territorial lands for farming, hunting and trapping animals for a fur trade and engaging in armed warfare with the tribes.

Larsen wrote that “a generation later, after the balance of power had indeed shifted, the Indian and white children of that Thanksgiving were striving to kill each other in the genocidal conflict known as King Philip’s War. At the end of that conflict most of the New England Indians were either exterminated or refugees among the French in Canada, or they were sold into slavery in the Carolina's by the Puritans.”

When we examine all of the facts, that first so-called “thanksgiving feast” at the Plymouth Colony as not a celebration of the harvest or even a recognition of gratitude for the help the natives gave to the Pilgrims.

It was not until President George Washington proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving on October 3, 1789, that the first real celebration known as Thanksgiving was held. President John Adams declared two additional celebrations of thanksgiving in 1798 and 1799. It was not until Abraham Lincoln declared it an annual holiday in 1863 that the concept of Thanksgiving as we currently know it was born.