Vessels of the Great Lakes:

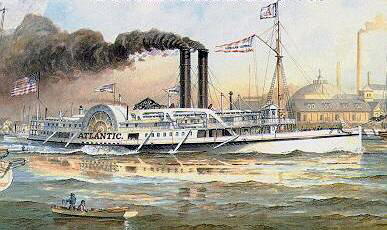

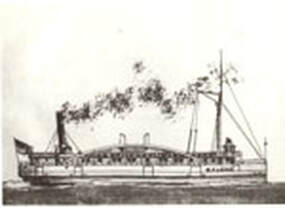

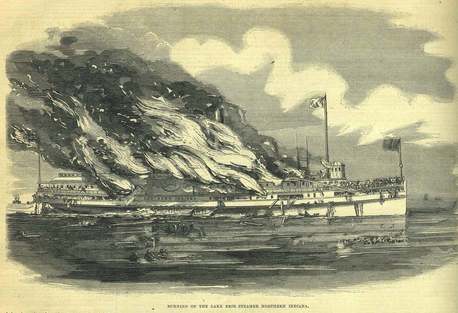

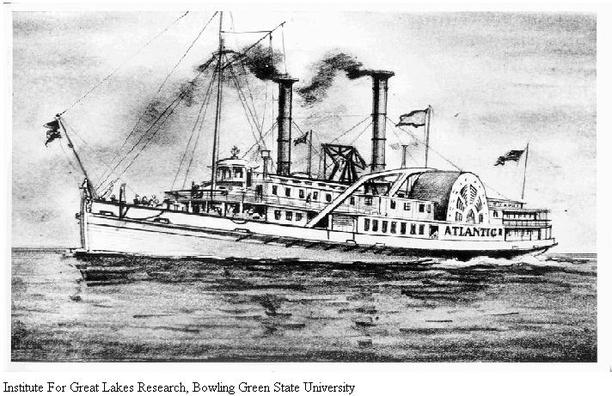

The Great Atlantic Disaster

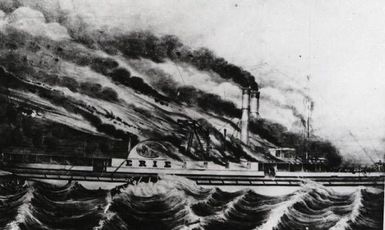

For years there was an old joke about how Lake Erie swallowed The Atlantic. It was a sick joke at best since it referred to one of the worst disasters on the Great Lakes. That wreck was the sinking of the steamer Atlantic and loss of between 130 and 250 lives following a collision with the steamer Ogdensburg. It happened in 1852, back in the days when steamboats were distinguished from propellers because they were driven by large wheels mounted on their sides. The Atlantic was such a boat.

For years there was an old joke about how Lake Erie swallowed The Atlantic. It was a sick joke at best since it referred to one of the worst disasters on the Great Lakes. That wreck was the sinking of the steamer Atlantic and loss of between 130 and 250 lives following a collision with the steamer Ogdensburg. It happened in 1852, back in the days when steamboats were distinguished from propellers because they were driven by large wheels mounted on their sides. The Atlantic was such a boat.

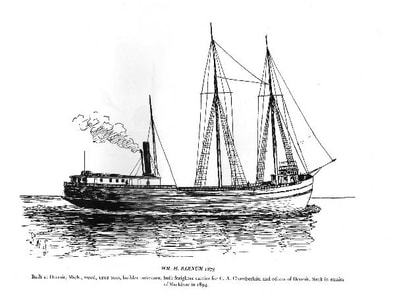

Sinking of the William H. Barnum

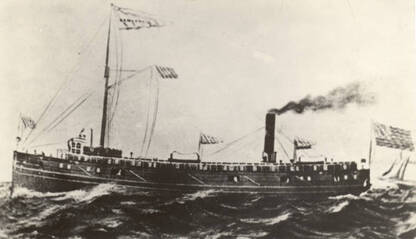

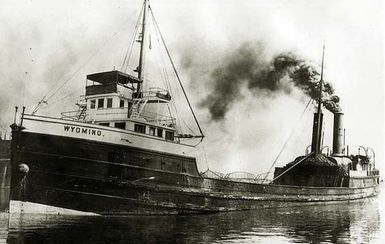

The wooden hulled steamer William H. Barnum had been on the lakes for 21 years at the time of its demise. Other vessels of its kind lasted a lot longer, but the Barnum was the victim of neglect. Thus in the spring of 1894, when the owners wanted the ship to carry a cargo of corn from Chicago to an unknown eastern port, and then proceed to dry dock for a rebuilding, insurance for the trip was not easy to obtain.

The wooden hulled steamer William H. Barnum had been on the lakes for 21 years at the time of its demise. Other vessels of its kind lasted a lot longer, but the Barnum was the victim of neglect. Thus in the spring of 1894, when the owners wanted the ship to carry a cargo of corn from Chicago to an unknown eastern port, and then proceed to dry dock for a rebuilding, insurance for the trip was not easy to obtain.

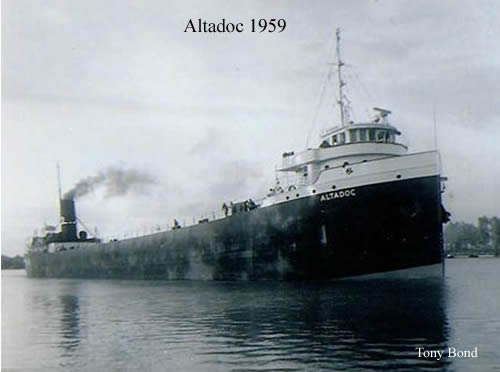

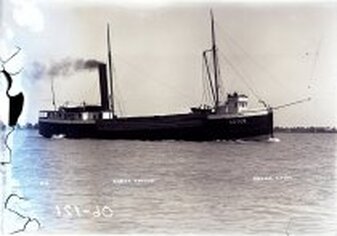

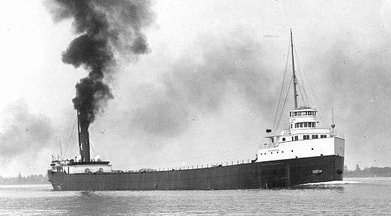

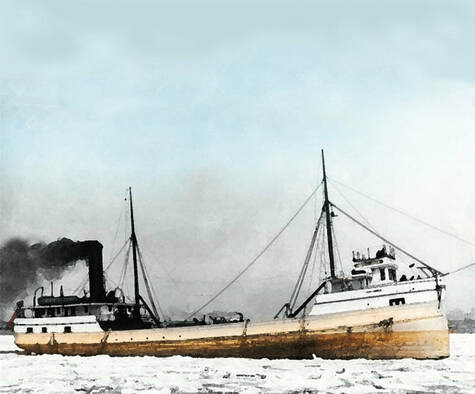

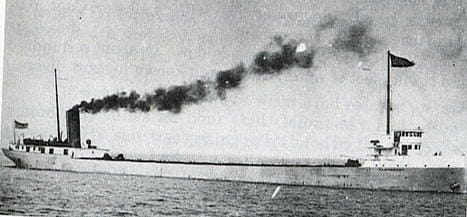

Wrecked Freighter Altadoc Sparked Tiny Tourist Attraction

It was an early winter gale on the Great Lakes that led to the destruction of the bulk carriers Altadoc, Agawa, Lambton and Martin. The date was Dec. 8, 1927. All four ships were driven aground and destroyed by the storm which packed near hurricane force winds of up to 70 miles an hour. The Altadoc, a Canadian-owned vessel, was steaming empty on Lake Superior, bound for Fort William, Ontario, when the storm drove it aground at Copper Harbor on Keweenaw Point, at the northern tip of Michigan.

It was an early winter gale on the Great Lakes that led to the destruction of the bulk carriers Altadoc, Agawa, Lambton and Martin. The date was Dec. 8, 1927. All four ships were driven aground and destroyed by the storm which packed near hurricane force winds of up to 70 miles an hour. The Altadoc, a Canadian-owned vessel, was steaming empty on Lake Superior, bound for Fort William, Ontario, when the storm drove it aground at Copper Harbor on Keweenaw Point, at the northern tip of Michigan.

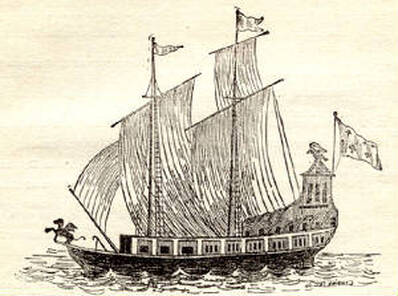

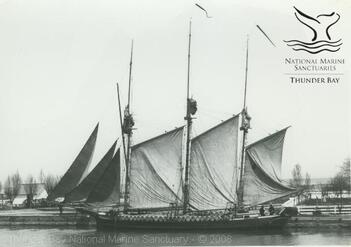

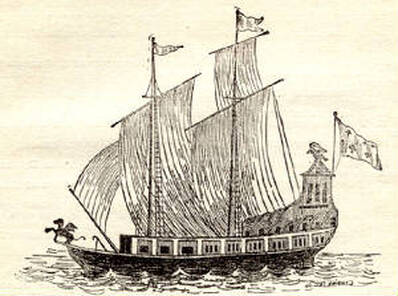

.LaSalle’s Griffin, First Great Lakes Ship

French explorer and fur trader Rene Robert Cavelier de la Salle built the Griffin, the first ship to ever navigate the Great Lakes, in 1670. It was a sailing ship hewn from fresh-cut trees along the Niagara River, at the mouth of Cayuga Creek near the place where the town of La Salle, New York, stands today. Old drawings are but guesses of what the Griffin looked like, based upon ship design of that period. It is said the vessel was small, ranging from 45 to 60 tons burden. It carried seven brass cannons so technically was a ship of war even though its purpose was for the transport of furs from the lakes to New York for shipment to Europe. It took those early carpenters all the winter of 1678-79 to complete the vessel. It was launched that May.

French explorer and fur trader Rene Robert Cavelier de la Salle built the Griffin, the first ship to ever navigate the Great Lakes, in 1670. It was a sailing ship hewn from fresh-cut trees along the Niagara River, at the mouth of Cayuga Creek near the place where the town of La Salle, New York, stands today. Old drawings are but guesses of what the Griffin looked like, based upon ship design of that period. It is said the vessel was small, ranging from 45 to 60 tons burden. It carried seven brass cannons so technically was a ship of war even though its purpose was for the transport of furs from the lakes to New York for shipment to Europe. It took those early carpenters all the winter of 1678-79 to complete the vessel. It was launched that May.

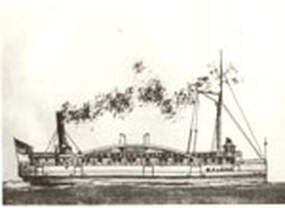

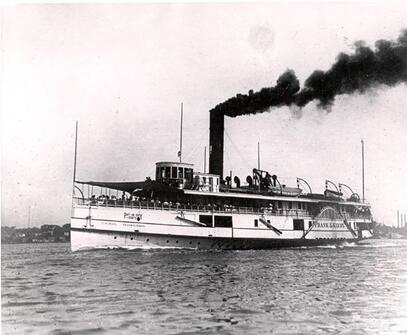

Big Blow Of 1880 Claimed The Alpena

Some people said Captain Nelson W. Napier should have known better than take the Goodrich Line steamer Alpena out of Grand Haven, Michigan, on that fateful trip to Chicago on the night of Oct. 15, 1880. It was a beautiful Indian Summer evening, but the barometer was falling fast, and there were forecasts of a major gale brewing even before Napier’s ship weighed anchor that evening. All along the coast that evening the storm signals were out. As an experienced Great Lakes navigator, Napier should have known the dangers. He probably thought he had enough time to get across Lake Michigan and under the lee of the Illinois coast before the storm hit.

Some people said Captain Nelson W. Napier should have known better than take the Goodrich Line steamer Alpena out of Grand Haven, Michigan, on that fateful trip to Chicago on the night of Oct. 15, 1880. It was a beautiful Indian Summer evening, but the barometer was falling fast, and there were forecasts of a major gale brewing even before Napier’s ship weighed anchor that evening. All along the coast that evening the storm signals were out. As an experienced Great Lakes navigator, Napier should have known the dangers. He probably thought he had enough time to get across Lake Michigan and under the lee of the Illinois coast before the storm hit.

The Haunting of Captain McLean

The freighter John M. Nicol was in trouble. The boat had been fighting a fierce northeaster on Lake Superior for several hours on the morning of September 16, 1901, and her seams were starting to open. Capt. William “Bill” McLean had the Nicol steaming hard for the shelter of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, racing against time to save his command. He reasoned that once he got the Nicol close enough to land, if things got too bad he would drive the boat aground to save the twenty-one members of his crew. This was his state of mind at about 10:00 AM when the Nichol came upon the steamer Hudson in a sinking condition, about eight miles off Eagle River.

The freighter John M. Nicol was in trouble. The boat had been fighting a fierce northeaster on Lake Superior for several hours on the morning of September 16, 1901, and her seams were starting to open. Capt. William “Bill” McLean had the Nicol steaming hard for the shelter of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, racing against time to save his command. He reasoned that once he got the Nicol close enough to land, if things got too bad he would drive the boat aground to save the twenty-one members of his crew. This was his state of mind at about 10:00 AM when the Nichol came upon the steamer Hudson in a sinking condition, about eight miles off Eagle River.

Steamship Alberta – "The Terror of the Lakes"

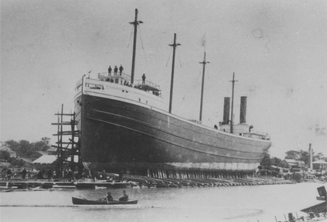

The steel steamship Alberta gained a nickname, "The Terror of the Lakes," for good reason. It kept colliding with other vessels and was involved in the crash that sent the steamer John Osborne to the bottom on Lake Superior in 1884. The Alberta and its sister ship, the Algoma, were both steel-hulled ships built in Scotland and brought across the Atlantic Ocean and up the St. Lawrence River in 1883 for service on the Great Lakes. The Alberta, a monster for its day at 264-feet, had to be cut into two parts at Montreal so it could be towed through the Weland Canal. Then it was reassembled at Buffalo. The Alberta and Algoma were the first steel ships ever to ply the Great Lakes. The Algoma only lasted two years. She went on the rocks, broke apart and sank at Isle Royal in 1885. Click for Details

The steel steamship Alberta gained a nickname, "The Terror of the Lakes," for good reason. It kept colliding with other vessels and was involved in the crash that sent the steamer John Osborne to the bottom on Lake Superior in 1884. The Alberta and its sister ship, the Algoma, were both steel-hulled ships built in Scotland and brought across the Atlantic Ocean and up the St. Lawrence River in 1883 for service on the Great Lakes. The Alberta, a monster for its day at 264-feet, had to be cut into two parts at Montreal so it could be towed through the Weland Canal. Then it was reassembled at Buffalo. The Alberta and Algoma were the first steel ships ever to ply the Great Lakes. The Algoma only lasted two years. She went on the rocks, broke apart and sank at Isle Royal in 1885. Click for Details

Christmas Tree Ship La Rubida

The 30-year-old schooner La Rubida was laden with 10,000 Christmas trees, probably bound for her home port of South Haven, Michigan, when it was driven ashore and wrecked near Naubinway on Lake Michigan, on November 25, 1906. Naubinway is a small community located on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula near the Wisconsin border. Captain A. E. Dow and his crew of the 75-foot-long wooden schooner managed to escape to shore in spite of the bitter cold, and found shelter after spending a terrible night on the beach.

The 30-year-old schooner La Rubida was laden with 10,000 Christmas trees, probably bound for her home port of South Haven, Michigan, when it was driven ashore and wrecked near Naubinway on Lake Michigan, on November 25, 1906. Naubinway is a small community located on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula near the Wisconsin border. Captain A. E. Dow and his crew of the 75-foot-long wooden schooner managed to escape to shore in spite of the bitter cold, and found shelter after spending a terrible night on the beach.

Dramatic Rescue On The A. A. Parker

The rescue of the 18 crew members and two dogs from the deck of the sinking steamer A. A. Parker remains among the annuals of the dramatic stories in the history of the U.S. Live Saving Service.

The Parker sank on Lake Superior, just off Grand Maras, on Sept. 19, 1903. The story of what happened, and just how close those sailors came to losing their lives, reads like the plot of a contemporary adventure film produced on a Hollywood set. You almost feel the danger just reading the dull pages of government records.

The rescue of the 18 crew members and two dogs from the deck of the sinking steamer A. A. Parker remains among the annuals of the dramatic stories in the history of the U.S. Live Saving Service.

The Parker sank on Lake Superior, just off Grand Maras, on Sept. 19, 1903. The story of what happened, and just how close those sailors came to losing their lives, reads like the plot of a contemporary adventure film produced on a Hollywood set. You almost feel the danger just reading the dull pages of government records.

Storm Destroys The Akeley

The steamship H. C. Akeley was only three years old when a furious November gale literally tore it into pieces, killing the captain and five other crew members on Lake Michigan in 1883. Had it not been for the courage of the crew of the schooner Driver, that stood by the stricken steamer to take aboard 12 other crew members who escaped on the ship’s only surviving lifeboat, the casualty count would have been much worse.

The steamship H. C. Akeley was only three years old when a furious November gale literally tore it into pieces, killing the captain and five other crew members on Lake Michigan in 1883. Had it not been for the courage of the crew of the schooner Driver, that stood by the stricken steamer to take aboard 12 other crew members who escaped on the ship’s only surviving lifeboat, the casualty count would have been much worse.

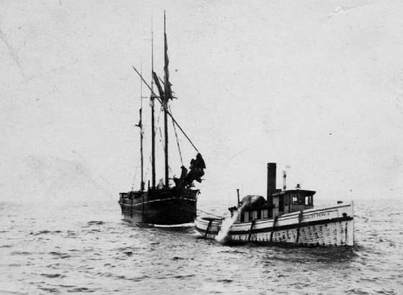

Adriatic And Baltic Lost In Same Lake Erie Gale

Fourteen sailors perished when the schooner barges Adriatic and Baltic broke loose from the tug that had them in tow and wrecked during a severe Lake Erie Gale in 1872. The barges were in a line of vessels in tow behind the tug Moore, believed to have been the William A. Moore that was on the Great Lakes that year. The vessels were all bound for Saginaw, Michigan, which means they were probably involved in carrying lumber to the mills at Tonawanda, New York. They were either returning without cargo or were laden with coal. That was standard cargo for lumber carriers on return trips from Lake Erie ports.

Fourteen sailors perished when the schooner barges Adriatic and Baltic broke loose from the tug that had them in tow and wrecked during a severe Lake Erie Gale in 1872. The barges were in a line of vessels in tow behind the tug Moore, believed to have been the William A. Moore that was on the Great Lakes that year. The vessels were all bound for Saginaw, Michigan, which means they were probably involved in carrying lumber to the mills at Tonawanda, New York. They were either returning without cargo or were laden with coal. That was standard cargo for lumber carriers on return trips from Lake Erie ports.

Wreck Of The Galena

The 193-foot-long wooden propeller slammed into the rocks with a sudden jolt that threw passengers from their bunks and rattled pans in the galley. Broadbridge grabbed the chadburn and sent the order to the engine room to reverse the engines. His first hope was that the ship could break free and that the hull was not severely damaged. But the steamer didn’t budge.

The 193-foot-long wooden propeller slammed into the rocks with a sudden jolt that threw passengers from their bunks and rattled pans in the galley. Broadbridge grabbed the chadburn and sent the order to the engine room to reverse the engines. His first hope was that the ship could break free and that the hull was not severely damaged. But the steamer didn’t budge.

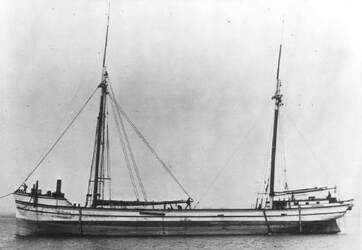

Strange Disappearance of the Thomas Hume

When the schooner Thomas Hume went missing in a Lake Michigan gale on May 21, 1891, everybody assumed that the ship sank. After a week passed and the usual trappings from such a disaster; floating timbers, life jackets, lifeboats and bodies, failed to turn up, people realized they had a mystery on their hands. The Hume had disappeared without a trace. The loss of the vessel remained a mystery until 2016 when a wreck, believed to be the Hume, was discovered in 200 feet on the bottom of Lake Michigan.

When the schooner Thomas Hume went missing in a Lake Michigan gale on May 21, 1891, everybody assumed that the ship sank. After a week passed and the usual trappings from such a disaster; floating timbers, life jackets, lifeboats and bodies, failed to turn up, people realized they had a mystery on their hands. The Hume had disappeared without a trace. The loss of the vessel remained a mystery until 2016 when a wreck, believed to be the Hume, was discovered in 200 feet on the bottom of Lake Michigan.

Remembering Historic Carrier Amasa Stone

Named for an American industrialist linked to tragedy, the Great Lakes steamship Amasa Stone served 55 successful years hauling grain, ore, coal and other goods between Duluth, Chicago and Buffalo. Her stripped-down hull continues to serve as a breakwater at the entrance to Charlevoix, Michigan, on the Lake Michigan coast. The Stone was built by Detroit Ship Building Co. at Wyandotte and launched for the Mesaba Steamship Co. in 1905. It was named for Amasha Stone, 1818-1883, who built railroads and invested in mills and education. Stone committed suicide after a railroad bridge he helped design collapsed over the Ashtabula River, carrying 159 passengers and railroad workers to their deaths in 1876.

Named for an American industrialist linked to tragedy, the Great Lakes steamship Amasa Stone served 55 successful years hauling grain, ore, coal and other goods between Duluth, Chicago and Buffalo. Her stripped-down hull continues to serve as a breakwater at the entrance to Charlevoix, Michigan, on the Lake Michigan coast. The Stone was built by Detroit Ship Building Co. at Wyandotte and launched for the Mesaba Steamship Co. in 1905. It was named for Amasha Stone, 1818-1883, who built railroads and invested in mills and education. Stone committed suicide after a railroad bridge he helped design collapsed over the Ashtabula River, carrying 159 passengers and railroad workers to their deaths in 1876.

Erie Horror Story

Chief engineer A. Welch’s story of survival aboard the burning freighter Clarion was enough to send a cold chill down the spine of the most hardened Great Lakes sailor. Welch and five other men found themselves trapped aboard the burning boat, in the night, with a serious winter gale blowing, in the middle of Lake Erie, and without a lifeboat. It happened the night of December 8, 1909. Welch told of leading his small band of men in a four-hour fight for their lives, and successfully holding back the flames until the steamer L. C Hanna came alongside. “The intense heat had driven us to about the limit of endurance when we were rescued,” he said. The other men, identified as second engineer John Graham, firemen Harry Murray, Theodore Larson and Joseph Baker, and cook Michael Toomey, praised Welch for his leadership during the crisis.

Chief engineer A. Welch’s story of survival aboard the burning freighter Clarion was enough to send a cold chill down the spine of the most hardened Great Lakes sailor. Welch and five other men found themselves trapped aboard the burning boat, in the night, with a serious winter gale blowing, in the middle of Lake Erie, and without a lifeboat. It happened the night of December 8, 1909. Welch told of leading his small band of men in a four-hour fight for their lives, and successfully holding back the flames until the steamer L. C Hanna came alongside. “The intense heat had driven us to about the limit of endurance when we were rescued,” he said. The other men, identified as second engineer John Graham, firemen Harry Murray, Theodore Larson and Joseph Baker, and cook Michael Toomey, praised Welch for his leadership during the crisis.

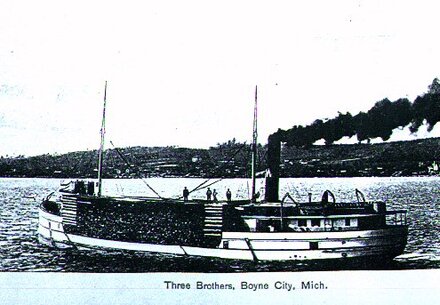

Three Brothers Slammed Into An Island

The aging lumber hooker Three Brothers wrecked during a Lake Michigan storm on Sept. 27, 1911, while steaming from Boyne City to Chicago with a cargo of hardwood. The 162-foot-long wooden vessel, under the command of Capt. Sam Christopher, began to leak shortly after leaving Boyne City. The leak worsened as the day progressed until the water overwhelmed the ship’s bilge pumps. Captain Christopher turned the vessel toward the nearest shore. He had full steam up when he ran the Three Brothers hard aground on South Manitou Island. The old boat literally plowed into the shoreline about 200 yards east of the lifesaving station. The crash split the ship’s bow open and dislodged the pilot house from the superstructure.

The aging lumber hooker Three Brothers wrecked during a Lake Michigan storm on Sept. 27, 1911, while steaming from Boyne City to Chicago with a cargo of hardwood. The 162-foot-long wooden vessel, under the command of Capt. Sam Christopher, began to leak shortly after leaving Boyne City. The leak worsened as the day progressed until the water overwhelmed the ship’s bilge pumps. Captain Christopher turned the vessel toward the nearest shore. He had full steam up when he ran the Three Brothers hard aground on South Manitou Island. The old boat literally plowed into the shoreline about 200 yards east of the lifesaving station. The crash split the ship’s bow open and dislodged the pilot house from the superstructure.

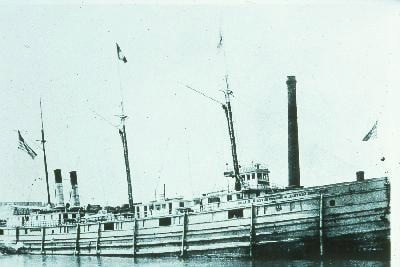

Bad Years for the Badger State

If records were kept for the volume of freight and passengers hauled on the Great Lakes, the propeller Badger State might have held one. The two hundred ten-foot long steamer competed on the route between Buffalo and Chicago in 1862. The boat was still going strong forty-seven years later, although by then it was reduced to the role of a tired lumber hooker when destroyed by a fire at Marine City, Michigan, on December 6, 1909. Four years before it burned, the Badger State fell into a period of disrepute. Still rigged as a passenger and freight hauler, the vessel was chartered by a Detroit gambling syndicate and was refurbished as a floating pleasure palace.

If records were kept for the volume of freight and passengers hauled on the Great Lakes, the propeller Badger State might have held one. The two hundred ten-foot long steamer competed on the route between Buffalo and Chicago in 1862. The boat was still going strong forty-seven years later, although by then it was reduced to the role of a tired lumber hooker when destroyed by a fire at Marine City, Michigan, on December 6, 1909. Four years before it burned, the Badger State fell into a period of disrepute. Still rigged as a passenger and freight hauler, the vessel was chartered by a Detroit gambling syndicate and was refurbished as a floating pleasure palace.

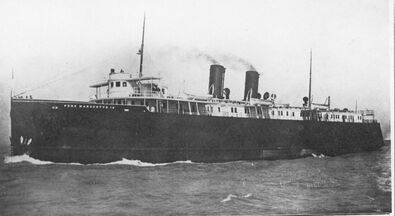

The Unexplained Loss of Pere Marquette No. 18

The sinking of the railroad car ferry Pere Marquette No. 18 on September 19, 1910 still remains one of Lake Michigan’s unsolved mysteries. The boat took twenty-nine passengers and crew members to the bottom with her and caused the deaths of two sailors from another vessel that fell from an overturned lifeboat to drown during rescue operations. Miraculously, another thirty-three of the sixty-two souls aboard the doomed ferry were pulled alive from the water. The cause of the sinking has remained a mystery. The seas were running high but the weather was fair. The vessel was not overloaded. Her engines and machinery were working. The vessel was making a first run for the ferry service after spending the summer operating as an excursion liner between Chicago and Waukegan. It passed a government inspection at Ludington the day before it sank. How, then, could it have happened?

The sinking of the railroad car ferry Pere Marquette No. 18 on September 19, 1910 still remains one of Lake Michigan’s unsolved mysteries. The boat took twenty-nine passengers and crew members to the bottom with her and caused the deaths of two sailors from another vessel that fell from an overturned lifeboat to drown during rescue operations. Miraculously, another thirty-three of the sixty-two souls aboard the doomed ferry were pulled alive from the water. The cause of the sinking has remained a mystery. The seas were running high but the weather was fair. The vessel was not overloaded. Her engines and machinery were working. The vessel was making a first run for the ferry service after spending the summer operating as an excursion liner between Chicago and Waukegan. It passed a government inspection at Ludington the day before it sank. How, then, could it have happened?

Wreck of the Goodyear

The ore carrier Frank H. Goodyear was the flagship of the Buffalo Steamship Company fleet. Named for the man who developed the famous Pullman railroad car, the Goodyear was distinguished by an ornate Pullman car attached to her deck. That railroad car, complete with a grand piano and fine furnishings, went to the bottom of Lake Huron with the Goodyear and seventeen terrified crew members after a collision with the freighter James B. Wood in thick fog off Point aux Barques. The date was May 23, 1910.

The ore carrier Frank H. Goodyear was the flagship of the Buffalo Steamship Company fleet. Named for the man who developed the famous Pullman railroad car, the Goodyear was distinguished by an ornate Pullman car attached to her deck. That railroad car, complete with a grand piano and fine furnishings, went to the bottom of Lake Huron with the Goodyear and seventeen terrified crew members after a collision with the freighter James B. Wood in thick fog off Point aux Barques. The date was May 23, 1910.

“She Will Be My Coffin”

Capt. John McKay had a love for the sea and an equal love for his fellow man. He had the best of both worlds. As an experienced master he commanded some well-known steamboats on the Great Lakes in the 1870s. Although his last command, the twelve-year-old steamer Manistee, was not so accommodating as some of the newer steamboats operating in 1883, people liked to book passage on it because they said the preferred traveling with “Johnny McKay.” They were drawn to the man because McKay loved people. He carried that devotion to his death when the Manistee foundered in a bad Lake Superior storm off Bayfield, Wisconsin, on November 16, 1883. One of the three survivors later said McKay refused to leave his sinking ship because nearly all the lifeboats were smashed or carried away by the storm and it was obvious that people were going to be left behind. “I am captain of this boat, and if she is a coffin for anybody, she will be my coffin,” he was quoted as saying.

Capt. John McKay had a love for the sea and an equal love for his fellow man. He had the best of both worlds. As an experienced master he commanded some well-known steamboats on the Great Lakes in the 1870s. Although his last command, the twelve-year-old steamer Manistee, was not so accommodating as some of the newer steamboats operating in 1883, people liked to book passage on it because they said the preferred traveling with “Johnny McKay.” They were drawn to the man because McKay loved people. He carried that devotion to his death when the Manistee foundered in a bad Lake Superior storm off Bayfield, Wisconsin, on November 16, 1883. One of the three survivors later said McKay refused to leave his sinking ship because nearly all the lifeboats were smashed or carried away by the storm and it was obvious that people were going to be left behind. “I am captain of this boat, and if she is a coffin for anybody, she will be my coffin,” he was quoted as saying.

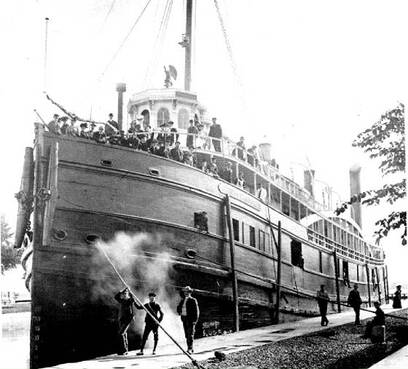

Strange Disappearance of the Soo City

After a successful twenty-year career on the Great Lakes, the ornate passenger steamer Soo City met her end in a cloak of mystery on the North Atlantic. Nineteen sailors died when the ship disappeared sometimes between November 14 and December 4, 1908, while steaming from Quebec down the Atlantic coast. The first that anyone knew something happened was when wreckage began washing ashore December 4 near North Sidney, Nova Scotia.

After a successful twenty-year career on the Great Lakes, the ornate passenger steamer Soo City met her end in a cloak of mystery on the North Atlantic. Nineteen sailors died when the ship disappeared sometimes between November 14 and December 4, 1908, while steaming from Quebec down the Atlantic coast. The first that anyone knew something happened was when wreckage began washing ashore December 4 near North Sidney, Nova Scotia.

Lake Huron’s Ghost Ship Kaliyuga

When Simon Langell built his big new steamer at the St. Clair Michigan shipyards in 1887, he named it Kaliyuga, an ancient name that was supposed to mean “age of iron.” It was an inappropriate name for this steamer, because, though it was built early during the age of iron ships, the Kaliyuga was among the last of the wooden-hulled steamers. Had it been made of iron, perhaps it might have been strong enough to withstand the storm that claimed it. The steamer foundered with all hands somewhere in Lake Huron on October 19, 1905.

When Simon Langell built his big new steamer at the St. Clair Michigan shipyards in 1887, he named it Kaliyuga, an ancient name that was supposed to mean “age of iron.” It was an inappropriate name for this steamer, because, though it was built early during the age of iron ships, the Kaliyuga was among the last of the wooden-hulled steamers. Had it been made of iron, perhaps it might have been strong enough to withstand the storm that claimed it. The steamer foundered with all hands somewhere in Lake Huron on October 19, 1905.

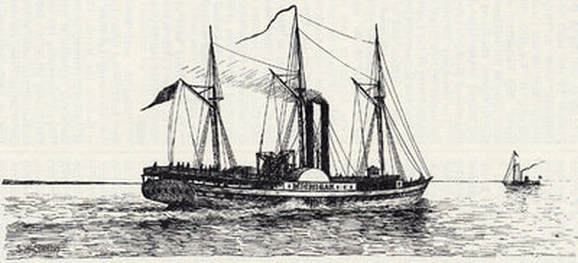

Strange Steamboat Walk-in-the-Water

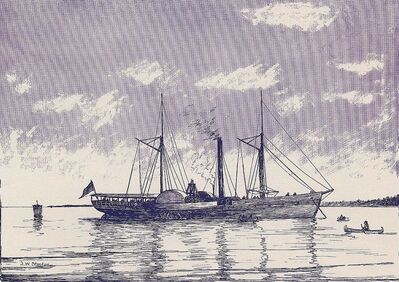

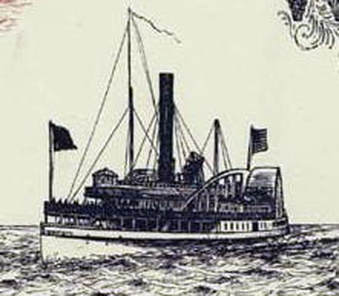

The first steamboat on the Great Lakes was the Walk-in-the-water, launched in 1818.There is a legend that the boat got its name from an Indian that watched Robert Fulton's steamboat Clermont as it huffed and puffed its way up the Hudson River just 11 years earlier. As the vessel moved upstream against the river current without the help of sails and wind, and he watched the turning paddle wheels, the native remarked that the vessel "walked in the water." While officially named the Walk-in-the-Water, the vessel was most commonly known to the people around the Great Lakes as "the steamboat." That was because it was the only operating steamboat during the three years of its existence.

The first steamboat on the Great Lakes was the Walk-in-the-water, launched in 1818.There is a legend that the boat got its name from an Indian that watched Robert Fulton's steamboat Clermont as it huffed and puffed its way up the Hudson River just 11 years earlier. As the vessel moved upstream against the river current without the help of sails and wind, and he watched the turning paddle wheels, the native remarked that the vessel "walked in the water." While officially named the Walk-in-the-Water, the vessel was most commonly known to the people around the Great Lakes as "the steamboat." That was because it was the only operating steamboat during the three years of its existence.

Saga of the Olive Jeannette

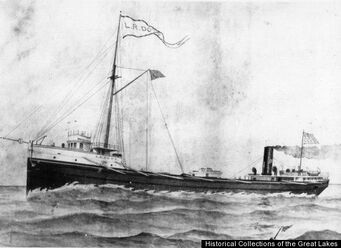

When the steamer Iosco and her tow, the schooner Olive Jeannette, foundered with all hands during a Lake Superior gale in 1905, lake men wondered if the schooner was cursed. The Jeannette was involved in an almost identical disaster, that time with the Iosco’s sister vessel, the L. R. Doty, during a storm on Lake Michigan in 1898. The Doty sank with all hands, but the Jeannette hoisted sail and survived to sail again. Seventeen sailors perished when the Doty, owned by the Cuyahoga Transit Company of Chicago, disappeared in the gale of October 25. Capt. David B. Cadotte, forty-eight-year-old master of the Jeannette, was credited with bringing his schooner through the storm against almost impossible odds. That story is among the best in the annals of lake lore. But it did not end here.

When the steamer Iosco and her tow, the schooner Olive Jeannette, foundered with all hands during a Lake Superior gale in 1905, lake men wondered if the schooner was cursed. The Jeannette was involved in an almost identical disaster, that time with the Iosco’s sister vessel, the L. R. Doty, during a storm on Lake Michigan in 1898. The Doty sank with all hands, but the Jeannette hoisted sail and survived to sail again. Seventeen sailors perished when the Doty, owned by the Cuyahoga Transit Company of Chicago, disappeared in the gale of October 25. Capt. David B. Cadotte, forty-eight-year-old master of the Jeannette, was credited with bringing his schooner through the storm against almost impossible odds. That story is among the best in the annals of lake lore. But it did not end here.

Chasing the Queen

Captain McKenzie was perplexed. Here he was, early in the day on August 20, 1903, piloting his boat through rough seas on Lake Erie, trying to rescue people from the sinking ore carrier Queen of the West, but the ill-fated boat was running away from him at full steam. McKenzie was probably thinking the Queen’s master, Capt. S. B. Massey of Ogdensburg, New York, had lost his senses. “She was running away from us with full steam,” he said. As the Cordorus gained and the two racing boats drew near each other, McKenzie said it was obvious that the people on the Queen of the West needed rescuing and very soon. He said the sea had washed away the lifeboats and several people were on deck, clinging to anything they could hang onto, as the moving boat settled lower and lower in the water.

Captain McKenzie was perplexed. Here he was, early in the day on August 20, 1903, piloting his boat through rough seas on Lake Erie, trying to rescue people from the sinking ore carrier Queen of the West, but the ill-fated boat was running away from him at full steam. McKenzie was probably thinking the Queen’s master, Capt. S. B. Massey of Ogdensburg, New York, had lost his senses. “She was running away from us with full steam,” he said. As the Cordorus gained and the two racing boats drew near each other, McKenzie said it was obvious that the people on the Queen of the West needed rescuing and very soon. He said the sea had washed away the lifeboats and several people were on deck, clinging to anything they could hang onto, as the moving boat settled lower and lower in the water.

Loss of the Iron Chief

A ship’s graveyard lies just off the northeast tip of Lower Michigan’s little peninsula, within sight of the old lighthouse at Lake Huron’s Pointe aux Barques. When the weather is good, sport divers like to visit some of the better-known wrecks, all bunched within a few miles of one another. But they are deep dives, many of them up to one hundred fifty feet down, and only the most experienced divers dare visit them. Among these wrecks is the Iron Chief, a two hundred twelve-foot wooden-hulled steamer that met its fate on October 3, 1904. Built as a schooner twenty-three years earlier in Detroit, the Iron Chief later was converted to be a steam barge. She never lost the grace she had as a sailing ship, and she carried her four masts until the day she sank.

A ship’s graveyard lies just off the northeast tip of Lower Michigan’s little peninsula, within sight of the old lighthouse at Lake Huron’s Pointe aux Barques. When the weather is good, sport divers like to visit some of the better-known wrecks, all bunched within a few miles of one another. But they are deep dives, many of them up to one hundred fifty feet down, and only the most experienced divers dare visit them. Among these wrecks is the Iron Chief, a two hundred twelve-foot wooden-hulled steamer that met its fate on October 3, 1904. Built as a schooner twenty-three years earlier in Detroit, the Iron Chief later was converted to be a steam barge. She never lost the grace she had as a sailing ship, and she carried her four masts until the day she sank.

The Haunting of Captain McLean

(Wreck of the Hudson)

The freighter John M. Nicol was in trouble. The boat had been fighting a fierce northeaster on Lake Superior for several hours on the morning of September 16, 1901, and her seams were starting to open. The pumps were not keeping up with the water surging into her vast hold. Then, just about dawn, chief engineer George E. Tretheway called Capt. William “Bill” McLean to the engine room to give him some more bad news. He showed McLean how the boat’s steam pipes were starting to work loose because of the wild wrenching and twisting the vessel’s hull was taking. “This boat can’t stand the strain much longer,” Tretheway warned. McLean had the Nicol steaming hard for the shelter of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, racing against time to save his command. He reasoned that once he got the Nicol close enough to land, if things got too bad he would drive the boat aground to save the twenty-one members of his crew. He spoke of his alternative plan to Tretheway. This was his state of mind at about 10:00 AM when the Nichol came upon the steamer Hudson in a sinking condition, about eight miles off Eagle River. So what could he do?

(Wreck of the Hudson)

The freighter John M. Nicol was in trouble. The boat had been fighting a fierce northeaster on Lake Superior for several hours on the morning of September 16, 1901, and her seams were starting to open. The pumps were not keeping up with the water surging into her vast hold. Then, just about dawn, chief engineer George E. Tretheway called Capt. William “Bill” McLean to the engine room to give him some more bad news. He showed McLean how the boat’s steam pipes were starting to work loose because of the wild wrenching and twisting the vessel’s hull was taking. “This boat can’t stand the strain much longer,” Tretheway warned. McLean had the Nicol steaming hard for the shelter of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, racing against time to save his command. He reasoned that once he got the Nicol close enough to land, if things got too bad he would drive the boat aground to save the twenty-one members of his crew. He spoke of his alternative plan to Tretheway. This was his state of mind at about 10:00 AM when the Nichol came upon the steamer Hudson in a sinking condition, about eight miles off Eagle River. So what could he do?

Top Heavy

The little steamer Henry Houghton made headlines the day it turned over in the Detroit River and sank, drowning two crew members sleeping below deck. It happened at 4:15 AM on September 9, 1902. The Houghton had arrived at Detroit only hours earlier with her hull deep in the water because of a heavy load of crushed stone brought from Marblehead, Ohio. The stone didn’t just fill the boat’s hold, but it was stacked high on the deck. It was obvious that the owners had this one hundred twenty-six-foot vessel loaded far beyond the weight capacity of one hundred fifty-one tons it was designed to carry. To intensify the weight, Capt. William Deeg said the boat came into heavy rail on Lake Erie, so the water was absorbed by the stone on the deck, adding even more weight at the top. In short, the boat was top-heavy.

The little steamer Henry Houghton made headlines the day it turned over in the Detroit River and sank, drowning two crew members sleeping below deck. It happened at 4:15 AM on September 9, 1902. The Houghton had arrived at Detroit only hours earlier with her hull deep in the water because of a heavy load of crushed stone brought from Marblehead, Ohio. The stone didn’t just fill the boat’s hold, but it was stacked high on the deck. It was obvious that the owners had this one hundred twenty-six-foot vessel loaded far beyond the weight capacity of one hundred fifty-one tons it was designed to carry. To intensify the weight, Capt. William Deeg said the boat came into heavy rail on Lake Erie, so the water was absorbed by the stone on the deck, adding even more weight at the top. In short, the boat was top-heavy.

The Engineer’s Story

When the tug Columbia arrived at East Tawas, Michigan, the evening of May 24, 1901, she carried two bedraggled and still dripping sailors, both wrapped in blankets and huddled in a warm cabin just over the engine room. They were second engineer Thomas Murphy and deckhand George McGinnis, the only survivors of the wrecked steamer Baltimore, which broke up on a shoal that morning off Au Sable during a Lake Huron gale. Click For Story

When the tug Columbia arrived at East Tawas, Michigan, the evening of May 24, 1901, she carried two bedraggled and still dripping sailors, both wrapped in blankets and huddled in a warm cabin just over the engine room. They were second engineer Thomas Murphy and deckhand George McGinnis, the only survivors of the wrecked steamer Baltimore, which broke up on a shoal that morning off Au Sable during a Lake Huron gale. Click For Story

Overheated Boilers

Capt. C. O. Flynn inadvertently set fire to his boat after it went aground on Lake Superior’s Michigan Island. It happened just after midnight on June 4, 1899, while Flynn’s command, the hundred-foot coastal steamer R. G. Stewart, was running through heavy fog at the western end of the lake. The boat was carrying three passengers and several head of cattle from Ontonagon to Duluth. The vessel struck a reef and Flynn spent the night in the pilot house, keeping his crew hard at work attempting to run the boat back into deep water under its own power. The overheated boilers set the vessel on fire.

Capt. C. O. Flynn inadvertently set fire to his boat after it went aground on Lake Superior’s Michigan Island. It happened just after midnight on June 4, 1899, while Flynn’s command, the hundred-foot coastal steamer R. G. Stewart, was running through heavy fog at the western end of the lake. The boat was carrying three passengers and several head of cattle from Ontonagon to Duluth. The vessel struck a reef and Flynn spent the night in the pilot house, keeping his crew hard at work attempting to run the boat back into deep water under its own power. The overheated boilers set the vessel on fire.

Saving The Crew of the E. B. Hale

The wooden steamer E. B. Hale lies in the boneyard of sunken ships off notorious Pointe aux Barques in Michigan’s Huron County. The story of the Hale’s sinking on October 8, 1897, and the crew’s narrow escape to the steamer Nebraska during a raging southwest gale, is a true tale of terror on the Great Lakes.

The wooden steamer E. B. Hale lies in the boneyard of sunken ships off notorious Pointe aux Barques in Michigan’s Huron County. The story of the Hale’s sinking on October 8, 1897, and the crew’s narrow escape to the steamer Nebraska during a raging southwest gale, is a true tale of terror on the Great Lakes.

The Burning Roanoke

From my book Terrifying Steamboat Stories

The steamer Roanoke seemed destined to burn. Flames swept the decks of the wooden hulled propeller twice. The final blaze destroyed and sank the steamer on August 7, 1894, while it was on its way from Port Huron to Washburn, Wisconsin, with a load of salt. The boat sank in one of the deepest parts of Lake Superior, about twenty miles off fourteen Mile Point, in twelve hundred feet of water. There were no casualties. The first burning happened on about May 17, 1890, while the Roanoke was tied up at the Northern Steamship Company dock in Buffalo.

From my book Terrifying Steamboat Stories

The steamer Roanoke seemed destined to burn. Flames swept the decks of the wooden hulled propeller twice. The final blaze destroyed and sank the steamer on August 7, 1894, while it was on its way from Port Huron to Washburn, Wisconsin, with a load of salt. The boat sank in one of the deepest parts of Lake Superior, about twenty miles off fourteen Mile Point, in twelve hundred feet of water. There were no casualties. The first burning happened on about May 17, 1890, while the Roanoke was tied up at the Northern Steamship Company dock in Buffalo.

Why Did They Die?

From the book Terrifying Steamboat Stories

There is an unsolved mystery surrounding the deaths of twenty-four sailors after the collision and sinking of the steamers Albany and Philadelphia on fog-shrouded Lake Huron. It happened during the early morning hours of November 7, 1893 after the two iron ships collided in a violent crash about twenty miles off Pointe aux Barques, Michigan. All of the lost sailors were crowded into one of two lifeboats launched from the Philadelphia. Their overturned yawl was found the next day by the Pointe aux Barques lifesavers. The body of one man, recovered a few hours later, indicated that something violent had happened. His skull was crushed.

From the book Terrifying Steamboat Stories

There is an unsolved mystery surrounding the deaths of twenty-four sailors after the collision and sinking of the steamers Albany and Philadelphia on fog-shrouded Lake Huron. It happened during the early morning hours of November 7, 1893 after the two iron ships collided in a violent crash about twenty miles off Pointe aux Barques, Michigan. All of the lost sailors were crowded into one of two lifeboats launched from the Philadelphia. Their overturned yawl was found the next day by the Pointe aux Barques lifesavers. The body of one man, recovered a few hours later, indicated that something violent had happened. His skull was crushed.

Surviving The Death Storm On Lake Erie

The story is a paradox. The steamer Wocoken was lost because the gale that blew on the night of October 14, 1893, used the shallow waters of Lake Erie to make waves with enough power to tear the ship apart. Yet the three men who survived the wreck lived because the vessel sank upright in the shallow water, with her masts and rigging suspended above the water. Thus it was that second mate J. P. Saph of Marine City, Michigan, wheelman J. H. Rice of Cleveland, and seaman Robert Crowding of Delaware were still alive when the storm abated the next day and Ontario lifesavers came from Port Huron to rescue them.

The story is a paradox. The steamer Wocoken was lost because the gale that blew on the night of October 14, 1893, used the shallow waters of Lake Erie to make waves with enough power to tear the ship apart. Yet the three men who survived the wreck lived because the vessel sank upright in the shallow water, with her masts and rigging suspended above the water. Thus it was that second mate J. P. Saph of Marine City, Michigan, wheelman J. H. Rice of Cleveland, and seaman Robert Crowding of Delaware were still alive when the storm abated the next day and Ontario lifesavers came from Port Huron to rescue them.

Death Cruise on the Western Reserve

The steamer Western Reserve, under the command of Capt. Albert Myers, left Cleveland Sunday afternoon, August 28, under sunny skies. It was a gala occasion for the family as the big ship moved out into the placid waters of Lake Erie, her mighty engines throbbing under their feet. No one dreamed then that the ship was taking them on a horror cruise that would end in death and disaster.

The steamer Western Reserve, under the command of Capt. Albert Myers, left Cleveland Sunday afternoon, August 28, under sunny skies. It was a gala occasion for the family as the big ship moved out into the placid waters of Lake Erie, her mighty engines throbbing under their feet. No one dreamed then that the ship was taking them on a horror cruise that would end in death and disaster.

Annie Young - Runaway Fire Ship

After twenty-one years, the wooden-hulled propeller Annie Young was considered an old vessel when it caught fire and burned off Lexington, Michigan on a breezy October day in 1890. Before the day was over nine crew members were dead and the Annie Young was a charred hulk at the bottom of Lake Huron. Plus the skipper of a rescue boat, the Edward Smith, was in line for a medal.

After twenty-one years, the wooden-hulled propeller Annie Young was considered an old vessel when it caught fire and burned off Lexington, Michigan on a breezy October day in 1890. Before the day was over nine crew members were dead and the Annie Young was a charred hulk at the bottom of Lake Huron. Plus the skipper of a rescue boat, the Edward Smith, was in line for a medal.

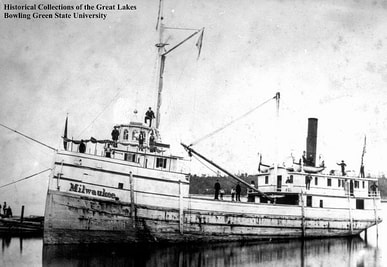

The Ship That Wouldn’t Turn Left

The collision was so violent that it knocked seaman Dennis Harrington off the deck to his death in fog-shrouded Lake Michigan. It happened somewhere in the middle of the lake on the night of July 8, 1886. The steam barge C. Hickox, lunber-laden and bound from Muskegon to Chicago, drove her bow deep into the port side of the steamer Milwaukee, which was traveling empty. The hole in the Milwaukee’s side sank the boat, but not before the C. Hickox took off the remaining members of its crew.

The collision was so violent that it knocked seaman Dennis Harrington off the deck to his death in fog-shrouded Lake Michigan. It happened somewhere in the middle of the lake on the night of July 8, 1886. The steam barge C. Hickox, lunber-laden and bound from Muskegon to Chicago, drove her bow deep into the port side of the steamer Milwaukee, which was traveling empty. The hole in the Milwaukee’s side sank the boat, but not before the C. Hickox took off the remaining members of its crew.

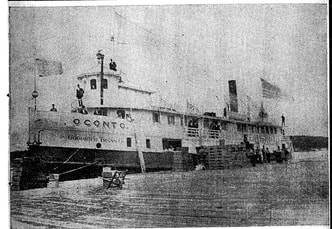

Wreck of the Oconto

First mate Charles Rearden of Port Huron told a story of real terror at sea after his ship, the steamer Oconto, got caught in a severe northeastern gale and blinding snowstorm the night of December 4, 1885. The one hundred forth-three-foot vessel, with Capt. G. W. McGregor of Lexington, Michigan at the helm, left Oscoda at 4:00 PM and was steaming north along the Michigan coast bound for Alpena. On board were forty-seven passengers and crew members, a hundred tons of freight, plus an unknown number of cows and horses. The upper decks were packed with cutters and sleighs, plus crates filled with about a hundred chickens and turkeys. The overloaded and outdated wooden hulled steamer was not prepared for the winter blast that awaited her on Lake Huron. What began as a three-hour, seventy-mile trip up the lake shore turned into a two-day period of extreme hardship.

First mate Charles Rearden of Port Huron told a story of real terror at sea after his ship, the steamer Oconto, got caught in a severe northeastern gale and blinding snowstorm the night of December 4, 1885. The one hundred forth-three-foot vessel, with Capt. G. W. McGregor of Lexington, Michigan at the helm, left Oscoda at 4:00 PM and was steaming north along the Michigan coast bound for Alpena. On board were forty-seven passengers and crew members, a hundred tons of freight, plus an unknown number of cows and horses. The upper decks were packed with cutters and sleighs, plus crates filled with about a hundred chickens and turkeys. The overloaded and outdated wooden hulled steamer was not prepared for the winter blast that awaited her on Lake Huron. What began as a three-hour, seventy-mile trip up the lake shore turned into a two-day period of extreme hardship.

“She Will Be My Coffin”

Capt. John McKay had a love for the sea and an equal love for his fellow man. He had the best of both worlds. As an experienced master he commanded some well-known steamboats on the Great Lakes in the 1870s. He carried that devotion to his death when the Manistee foundered in a bad Lake Superior storm off Bayfield, Wisconsin, on November 16, 1883. One of the three survivors later said McKay refused to leave his sinking ship because nearly all the lifeboats were smashed or carried away by the storm and it was obvious that people were going to be left behind. “I am captain of this boat, and if she is a coffin for anybody, she will be my coffin,” he was quoted as saying.

Capt. John McKay had a love for the sea and an equal love for his fellow man. He had the best of both worlds. As an experienced master he commanded some well-known steamboats on the Great Lakes in the 1870s. He carried that devotion to his death when the Manistee foundered in a bad Lake Superior storm off Bayfield, Wisconsin, on November 16, 1883. One of the three survivors later said McKay refused to leave his sinking ship because nearly all the lifeboats were smashed or carried away by the storm and it was obvious that people were going to be left behind. “I am captain of this boat, and if she is a coffin for anybody, she will be my coffin,” he was quoted as saying.

Sinking of the East Saginaw

It was for the lack of a tugboat that the steam barge East Saginaw was lost on Lake Huron. The trouble began about 10:30 PM on September, 25, 1883, when the steamer, with four barges in tow, ran up on Craine’s Point about a mile south of the Harbor Beach, Michigan breakwater. Capt. Harry Richardson said he was running the boat against a northwesterly gale and trying to make the harbor when the vessel hit the rocks. The crash broke the boat’s rudder and the subsequent pounding put holes in the wooden hull.

It was for the lack of a tugboat that the steam barge East Saginaw was lost on Lake Huron. The trouble began about 10:30 PM on September, 25, 1883, when the steamer, with four barges in tow, ran up on Craine’s Point about a mile south of the Harbor Beach, Michigan breakwater. Capt. Harry Richardson said he was running the boat against a northwesterly gale and trying to make the harbor when the vessel hit the rocks. The crash broke the boat’s rudder and the subsequent pounding put holes in the wooden hull.

Wreck Of The Galena

Captain Warren Broadbridge spent Tuesday afternoon, September 24, 1872 supervising the loading of 272,000 feet of lumber. He also had a wary eye on the sky while his boat, the propeller Galena, lay moored at Alpena, Michigan. Even when he brought the vessel into port earlier in the day the weather was windy and boisterous. By late in the afternoon it was clear that a gale from the southwest was building. Broadbride knew his scheduled trip to Chicago was going to be rough. He was still considering the weather as passengers began boarding the Galena that evening. Departure time was 11 p.m. so the five passengers booked for the trip didn’t start arriving until after supper. He made the decision at ten o’clock to sail on time in spite of the looming storm. It was a serious mistake.

Captain Warren Broadbridge spent Tuesday afternoon, September 24, 1872 supervising the loading of 272,000 feet of lumber. He also had a wary eye on the sky while his boat, the propeller Galena, lay moored at Alpena, Michigan. Even when he brought the vessel into port earlier in the day the weather was windy and boisterous. By late in the afternoon it was clear that a gale from the southwest was building. Broadbride knew his scheduled trip to Chicago was going to be rough. He was still considering the weather as passengers began boarding the Galena that evening. Departure time was 11 p.m. so the five passengers booked for the trip didn’t start arriving until after supper. He made the decision at ten o’clock to sail on time in spite of the looming storm. It was a serious mistake.

Duncan and Christy – Surviving The Asia Disaster

The wreck of the steamer Asia in Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay on September 14, 1882, had all the elements of a Hollywood production: terror, drama at sea, a captain who displayed wanton disregard for human life, and even romance. There were just two survivors from among the one hundred twenty-five souls aboard the Asia. And they were seventeen-year-old Duncan A. Tinkis and eighteen-year-old Christy Ann Morrison. They stumbled ashore together in a remote Ontario wilderness after spending a terrible night in an open boat surrounded by dead bodies. From my book "Terrifying Steamboat Stories." Click To Read More

The wreck of the steamer Asia in Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay on September 14, 1882, had all the elements of a Hollywood production: terror, drama at sea, a captain who displayed wanton disregard for human life, and even romance. There were just two survivors from among the one hundred twenty-five souls aboard the Asia. And they were seventeen-year-old Duncan A. Tinkis and eighteen-year-old Christy Ann Morrison. They stumbled ashore together in a remote Ontario wilderness after spending a terrible night in an open boat surrounded by dead bodies. From my book "Terrifying Steamboat Stories." Click To Read More

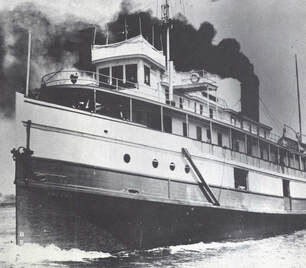

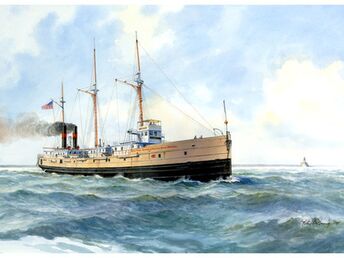

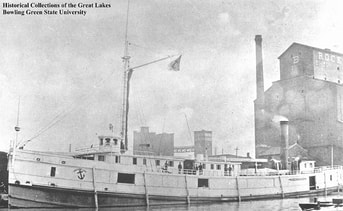

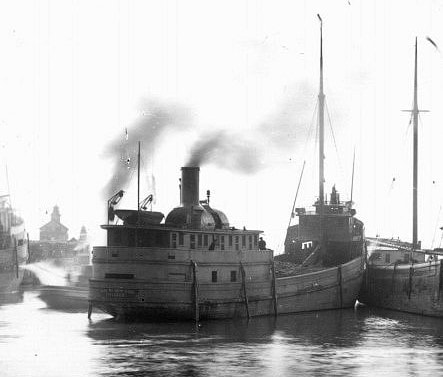

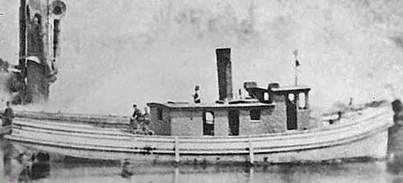

Historic Tug Ella G. Stone

From the day it was launched at Algonac in 1881 until the day it was destroyed by a forest fire near Duluth in 1918, the wooden hulled tug Ella G. Stone played an important role in the history and development of the Lake Superior region. She was launched as the E. L. Mason, but the name was changed in 1883 to Ella G. Stone, the name the tug carried for the remainder of its years on the lakes. The Stone was used in towing and other tug services at Two Harbors, Minnesota.

From the day it was launched at Algonac in 1881 until the day it was destroyed by a forest fire near Duluth in 1918, the wooden hulled tug Ella G. Stone played an important role in the history and development of the Lake Superior region. She was launched as the E. L. Mason, but the name was changed in 1883 to Ella G. Stone, the name the tug carried for the remainder of its years on the lakes. The Stone was used in towing and other tug services at Two Harbors, Minnesota.

The Cook Who Commandeered Her Ship

In the old days women never played leadership roles on Great Lakes ships. But they were always on the boats and once in a while they proved their seamanship abilities. Such was the case of Martha Hart, cook aboard the steamer Hastings, who brought the boat and its passengers safely home to Oswego, New York, from an Independence Day trip across Lake Ontario in 1878, after the officers abandoned the bridge and the wheelman lost his bearings.

In the old days women never played leadership roles on Great Lakes ships. But they were always on the boats and once in a while they proved their seamanship abilities. Such was the case of Martha Hart, cook aboard the steamer Hastings, who brought the boat and its passengers safely home to Oswego, New York, from an Independence Day trip across Lake Ontario in 1878, after the officers abandoned the bridge and the wheelman lost his bearings.

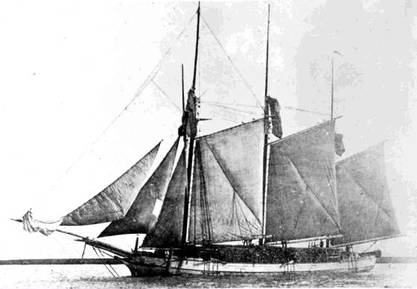

Rouse Simmons - Lost Christmas Tree Ship

Rats were part of the lore of sailing ships in the old days. The creatures seemed to always be around ship’s galleys where quantities of flour, sugar, lard and other staples for preparing meals were stored. For some odd reason, sailors included them in their superstitions. They believed that rats were able to predict the future. When rats were seen leaving a ship, sailors believed it was a very bad omen and that the ship probably was going to sink. That is just what happened to the three-mast schooner Rouse Simmons as the crew was preparing it for a trip across Lake Michigan in November, 1912. The boat was sailing from Chicago to Manistique, Mich. to pick up a load of Christmas trees. The Simmons arrived at Manistique, loaded up on trees, then sailed off into a stormy sea and was never seen again.

Rats were part of the lore of sailing ships in the old days. The creatures seemed to always be around ship’s galleys where quantities of flour, sugar, lard and other staples for preparing meals were stored. For some odd reason, sailors included them in their superstitions. They believed that rats were able to predict the future. When rats were seen leaving a ship, sailors believed it was a very bad omen and that the ship probably was going to sink. That is just what happened to the three-mast schooner Rouse Simmons as the crew was preparing it for a trip across Lake Michigan in November, 1912. The boat was sailing from Chicago to Manistique, Mich. to pick up a load of Christmas trees. The Simmons arrived at Manistique, loaded up on trees, then sailed off into a stormy sea and was never seen again.

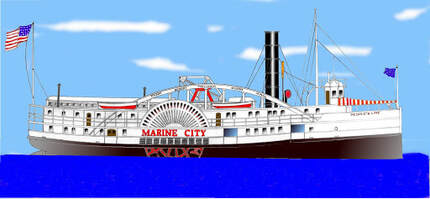

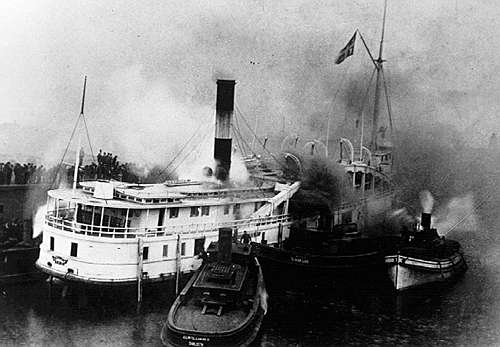

Burning of the Marine City

When the side-wheeler Marine City went up in smoke off Lake Huron’s Sturgeon Point on August 28, 1880, the fire came close to being a major marine disaster. As it was, eight of the estimated one hundred fifty-five passengers and crew members died. That the others survived was considered a miracle. Get The Story

When the side-wheeler Marine City went up in smoke off Lake Huron’s Sturgeon Point on August 28, 1880, the fire came close to being a major marine disaster. As it was, eight of the estimated one hundred fifty-five passengers and crew members died. That the others survived was considered a miracle. Get The Story

Raising The St. Catherines

When you think of the primitive equipment they worked with in their day, divers and salvagers did amazing things before the turn of the century. Few salvage operations, however, were as spectacular as the raising of the propeller City of St. Catherines, a Canadian vessel sunk in a collision off White Rick, Michigan, on July 12, 1880. The St. Catherines, under the command of a Captain McMaugh, was making a fast trip from Montreal to Chicago with passengers and freight when it collided with the George H. Morse, a down bound steam barge, and sank in 90 feet of water.

When you think of the primitive equipment they worked with in their day, divers and salvagers did amazing things before the turn of the century. Few salvage operations, however, were as spectacular as the raising of the propeller City of St. Catherines, a Canadian vessel sunk in a collision off White Rick, Michigan, on July 12, 1880. The St. Catherines, under the command of a Captain McMaugh, was making a fast trip from Montreal to Chicago with passengers and freight when it collided with the George H. Morse, a down bound steam barge, and sank in 90 feet of water.

Tragic Capsizing Of The H. Rand

The 107-foot schooner H. Rand capsized in a gale in Lake Michigan, off Port Washington, Wisconsin, on May 24, 1901, killing the crew of four. Experienced sailors said they had warned the boat’s master, Captain Ralph Jefferson, that his habit of sailing with a short crew was setting the stage for disaster. They said a small crew was unable to handle a three-mast sailing ship like the Rand in a storm. They appear to have been right.

The 107-foot schooner H. Rand capsized in a gale in Lake Michigan, off Port Washington, Wisconsin, on May 24, 1901, killing the crew of four. Experienced sailors said they had warned the boat’s master, Captain Ralph Jefferson, that his habit of sailing with a short crew was setting the stage for disaster. They said a small crew was unable to handle a three-mast sailing ship like the Rand in a storm. They appear to have been right.

Saving the Crew of the New York

Fifteen sailors owed their lives to the plucky crew of the Canadian schooner Nemesis when their vessel, the propeller New York, was lost in a Lake Huron gale on October 15, 1876. Only one man died when the storm swamped the New York, sending it to the bottom off Forestville, Michigan. Fireman William Sparks of Buffalo fell overboard attempting to climb from a tossing lifeboat to the deck of the Nemesis. They said Sparks was exhausted from the five hours he spent in the open boat and lost his grip.

Fifteen sailors owed their lives to the plucky crew of the Canadian schooner Nemesis when their vessel, the propeller New York, was lost in a Lake Huron gale on October 15, 1876. Only one man died when the storm swamped the New York, sending it to the bottom off Forestville, Michigan. Fireman William Sparks of Buffalo fell overboard attempting to climb from a tossing lifeboat to the deck of the Nemesis. They said Sparks was exhausted from the five hours he spent in the open boat and lost his grip.

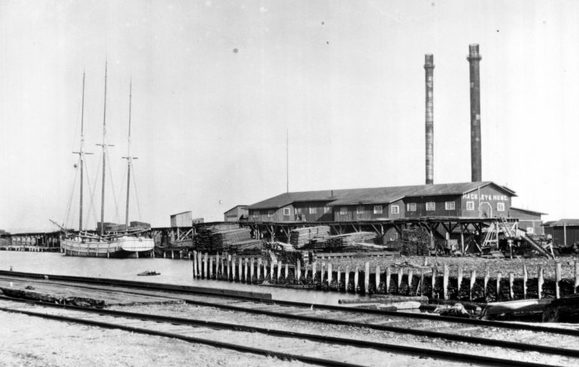

Historic Tug Ella G. Stone

From the day it was launched at Algonac in 1881 until the day it was destroyed by a forest fire near Duluth in 1918, the wooden hulled tug Ella G. Stone played an important role in the history and development of the Lake Superior region. She was launched as the E. L. Mason, but the name was changed in 1883 to Ella G. Stone, the name the tug carried for the remainder of its years on the lakes. The Stone was used in towing and other tug services at Two Harbors, Minnesota. There it was put to work bringing stone, concrete and other building materials for construction of the ore docks that made that harbor a major shipping port in the nation’s steel industry.

From the day it was launched at Algonac in 1881 until the day it was destroyed by a forest fire near Duluth in 1918, the wooden hulled tug Ella G. Stone played an important role in the history and development of the Lake Superior region. She was launched as the E. L. Mason, but the name was changed in 1883 to Ella G. Stone, the name the tug carried for the remainder of its years on the lakes. The Stone was used in towing and other tug services at Two Harbors, Minnesota. There it was put to work bringing stone, concrete and other building materials for construction of the ore docks that made that harbor a major shipping port in the nation’s steel industry.

Why Did They Hit?

The collision that sank the steamer Pewabic and took an estimated one hundred lives in Lake Huron’s Thunder Bay is still counted among the worst of the Great Lake disasters. It also remains among the unsolved mysteries of the lakes. It happened when a sister ship, the Meteor, hit the Pewabic, sinking her at dusk, about 8:30 PM on August 9, 1865. The puzzle about the incident was that both vessels from the Lake Superior Lane were operated by experienced crews who should have not made such a mistake. The lake was calm, the night was clear, and survivors from the Pewabic said they could see the light of the Meteor coming for miles before the collision.

The collision that sank the steamer Pewabic and took an estimated one hundred lives in Lake Huron’s Thunder Bay is still counted among the worst of the Great Lake disasters. It also remains among the unsolved mysteries of the lakes. It happened when a sister ship, the Meteor, hit the Pewabic, sinking her at dusk, about 8:30 PM on August 9, 1865. The puzzle about the incident was that both vessels from the Lake Superior Lane were operated by experienced crews who should have not made such a mistake. The lake was calm, the night was clear, and survivors from the Pewabic said they could see the light of the Meteor coming for miles before the collision.

Lost Treasure Ship – Keystone State

The steamship Keystone State was thought to have been carrying many thousands of dollars in gold and silver coins in its safe. The trick for many years was to find the wreck. The vessel took thirty-three souls to their death when it disappeared on Saturday, November 9, 1861, somewhere on Lake Huron. The steamer encountered a furious storm on Lake Huron and never made port. She was last seen rolling heavily on high seas somewhere off Point aux Barques, Michigan. There were no survivors so the story of what happened to the ship was never told. Behold, the wreck was found in 2013 by Michigan diver Dave Trotter and other divers some 30 miles northeast of Harrisville, an estimated 50 miles from where it was last seen. The wreck sits upright about 175 feet at the bottom of Lake Huron. Trotter reports that the stern is broken up, but the engine and large side wheels are still in place. No mention was made of a treasure in the vessel’s safe.

The steamship Keystone State was thought to have been carrying many thousands of dollars in gold and silver coins in its safe. The trick for many years was to find the wreck. The vessel took thirty-three souls to their death when it disappeared on Saturday, November 9, 1861, somewhere on Lake Huron. The steamer encountered a furious storm on Lake Huron and never made port. She was last seen rolling heavily on high seas somewhere off Point aux Barques, Michigan. There were no survivors so the story of what happened to the ship was never told. Behold, the wreck was found in 2013 by Michigan diver Dave Trotter and other divers some 30 miles northeast of Harrisville, an estimated 50 miles from where it was last seen. The wreck sits upright about 175 feet at the bottom of Lake Huron. Trotter reports that the stern is broken up, but the engine and large side wheels are still in place. No mention was made of a treasure in the vessel’s safe.

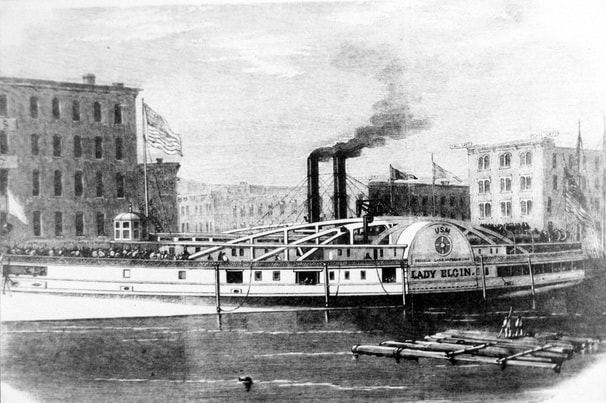

Was The Lady Elgin Cursed?

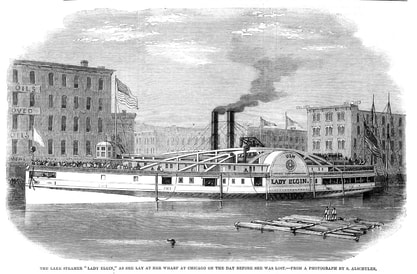

Some said the side-wheeled steamer Lady Elgin bore a curse from the day it was launched at Buffalo, New York, in 1851. That is because the engine and boilers came from the Cleopatra, an ocean slave trader that was confiscated by the U. S. Navy. But nobody dreamed that the Lady Elgin would be remembered as one of the worst disasters in Great Lakes history. When she was sunk in a collision on Lake Michigan, off Winnetka, Illinois, on September 8, 1860, an estimated two hundred eighty-seven passengers and crew members perished.

Some said the side-wheeled steamer Lady Elgin bore a curse from the day it was launched at Buffalo, New York, in 1851. That is because the engine and boilers came from the Cleopatra, an ocean slave trader that was confiscated by the U. S. Navy. But nobody dreamed that the Lady Elgin would be remembered as one of the worst disasters in Great Lakes history. When she was sunk in a collision on Lake Michigan, off Winnetka, Illinois, on September 8, 1860, an estimated two hundred eighty-seven passengers and crew members perished.

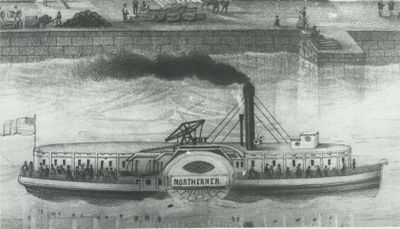

Mystery Wreck Northerner

The Northerner, under command of Capt. Darius Cole, was steaming north from Cleveland to Saginaw with one hundred thirty-four passengers and crew members, and about fifty tons of mixed freight. The Forest Queen, also a side-wheeled steamship, was bound down that night from Point aux Barques, Michigan. Her master was a man named Woodworth. The night was dark and foggy when the two boats, lighted only by the dim glow of kerosene lamps, crossed each other’s path at the wrong moment. The Forest Queen struck the starboard bow of the Northerner, cutting the ship almost in two about twenty feet back from the stem.

The Northerner, under command of Capt. Darius Cole, was steaming north from Cleveland to Saginaw with one hundred thirty-four passengers and crew members, and about fifty tons of mixed freight. The Forest Queen, also a side-wheeled steamship, was bound down that night from Point aux Barques, Michigan. Her master was a man named Woodworth. The night was dark and foggy when the two boats, lighted only by the dim glow of kerosene lamps, crossed each other’s path at the wrong moment. The Forest Queen struck the starboard bow of the Northerner, cutting the ship almost in two about twenty feet back from the stem.

The Walk-in-the-Water

Even though she lived only three years the steamboat Walk-in-the-Water made a dramatic mark on Great Lakes history. The Walk-in-the-Water was built in 1818 and was one of the pioneer steamboats of the world. It was the first steam ship built on Lake Erie. It also was the first steamship to travel on Lakes Erie, St. Clair, Huron and Michigan, and make the trip up the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers. It was the first steamship to offer passenger and freight service on Lake Erie between Buffalo and Detroit. And it was the first steamer to wreck on Lake Erie.

Even though she lived only three years the steamboat Walk-in-the-Water made a dramatic mark on Great Lakes history. The Walk-in-the-Water was built in 1818 and was one of the pioneer steamboats of the world. It was the first steam ship built on Lake Erie. It also was the first steamship to travel on Lakes Erie, St. Clair, Huron and Michigan, and make the trip up the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers. It was the first steamship to offer passenger and freight service on Lake Erie between Buffalo and Detroit. And it was the first steamer to wreck on Lake Erie.

The Mate's Radio Call

He didn't know it at the moment, but First Mate Elmer Fleming's last second effort to send a radio call for help saved his life. Fleming was aboard the freighter Carl D. Bradley as the ship was breaking up under his feet during a Lake Michigan gale on Nov. 18, 1958. The boat went down so quickly and so unexpectedly crew members barely had time to get life jackets on before they were in the water. But Fleming's impulsive action at 5:31 p.m. saved Fleming and only one other member of the Bradley's ill-fated crew. Deckhand Frank Mayes also survived the sinking.

He didn't know it at the moment, but First Mate Elmer Fleming's last second effort to send a radio call for help saved his life. Fleming was aboard the freighter Carl D. Bradley as the ship was breaking up under his feet during a Lake Michigan gale on Nov. 18, 1958. The boat went down so quickly and so unexpectedly crew members barely had time to get life jackets on before they were in the water. But Fleming's impulsive action at 5:31 p.m. saved Fleming and only one other member of the Bradley's ill-fated crew. Deckhand Frank Mayes also survived the sinking.

Wreck Of The Edenborn and Madeira

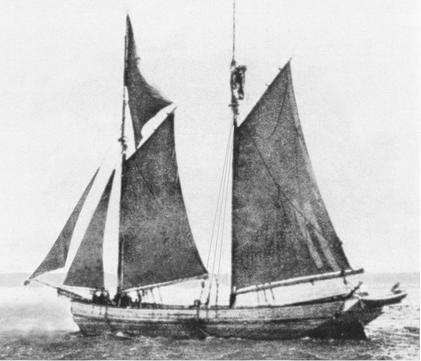

They called it the Mataafa Storm because it wrecked the steamship Mataafa in a deadly disaster off the Duluth harbor. But the November 1905 gale that claimed the Mataafa also left 20 other vessels wrecked or damaged and claimed 32 lives along the Lake Superior coast. The wrecks included the schooner-barge Madeira and the steamer William Edenborn, which had her in tow. The Madeira was a large vessel in its day, measuring 436 feet in length and 50 feet wide. Even though designed to be towed the vessel was provided with three masts and carried sails in case they were needed. Sometimes the sails were raised to assist the towing vessel. She was rigged as a schooner. The Madeira was in ballast and up-bound, under tow behind the Edenborn on Nov. 28 when both vessels were caught in the northeast gale packing winds up to 70 miles per hour off the Apostic Islands.

They called it the Mataafa Storm because it wrecked the steamship Mataafa in a deadly disaster off the Duluth harbor. But the November 1905 gale that claimed the Mataafa also left 20 other vessels wrecked or damaged and claimed 32 lives along the Lake Superior coast. The wrecks included the schooner-barge Madeira and the steamer William Edenborn, which had her in tow. The Madeira was a large vessel in its day, measuring 436 feet in length and 50 feet wide. Even though designed to be towed the vessel was provided with three masts and carried sails in case they were needed. Sometimes the sails were raised to assist the towing vessel. She was rigged as a schooner. The Madeira was in ballast and up-bound, under tow behind the Edenborn on Nov. 28 when both vessels were caught in the northeast gale packing winds up to 70 miles per hour off the Apostic Islands.

Steamer Eber Ward Sunk By Ice

Five sailors died when thick ice at the Straits of Mackinac punched a hole in the wooden hull and sank the 11-year-old steamer Eber Ward on April 9, 1909. The 213-foot-long bulk freighter was laden with corn after apparently spending a winter moored at Chicago. She was among the first lake vessels punching their way through the ice at the straits which was usually among the last obstacles to getting the spring shipping season underway between Buffalo and Chicago and all ports in between.

Five sailors died when thick ice at the Straits of Mackinac punched a hole in the wooden hull and sank the 11-year-old steamer Eber Ward on April 9, 1909. The 213-foot-long bulk freighter was laden with corn after apparently spending a winter moored at Chicago. She was among the first lake vessels punching their way through the ice at the straits which was usually among the last obstacles to getting the spring shipping season underway between Buffalo and Chicago and all ports in between.

Historic Ship Dover Lost In Ecorse Blaze

When a fire swept a number of Great Lakes vessels laid up for the winter at Ecorse, Michigan in 1932, the side-wheeler Dover was among the boats that burned. The Dover was the final name given to the historic steamship Frank E. Kirby, a familiar sight on the lakes for 42 years. Launched at Wyandotte in 1890, the Kirby was a steel-hulled side-wheeler designed for passenger service. She bore the name of well-known Nineteenth Century naval architect Frank E. Kirby.

When a fire swept a number of Great Lakes vessels laid up for the winter at Ecorse, Michigan in 1932, the side-wheeler Dover was among the boats that burned. The Dover was the final name given to the historic steamship Frank E. Kirby, a familiar sight on the lakes for 42 years. Launched at Wyandotte in 1890, the Kirby was a steel-hulled side-wheeler designed for passenger service. She bore the name of well-known Nineteenth Century naval architect Frank E. Kirby.

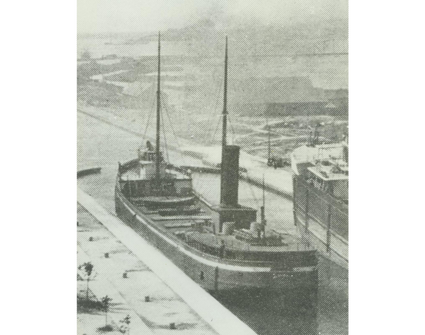

Pilot Error Sank The D. R. Hanna

A blunder by the pilot of the Great Lakes Freighter Quincy A. Shaw set the stage for a collision that sank the grain carrier D. R. Hanna off Thunder Bay on May 16, 1919. Both steel carriers were approaching each other in light fog in the afternoon hours, but the Hanna, Captain S. B. Massey at the helm, was steaming out of the established downbound shipping lane, which meant the boats were set up for an unconventional starboard to starboard passage. Great Lakes carriers normally followed routes on the lakes that called for port-to-port side passing when they crossed paths.

A blunder by the pilot of the Great Lakes Freighter Quincy A. Shaw set the stage for a collision that sank the grain carrier D. R. Hanna off Thunder Bay on May 16, 1919. Both steel carriers were approaching each other in light fog in the afternoon hours, but the Hanna, Captain S. B. Massey at the helm, was steaming out of the established downbound shipping lane, which meant the boats were set up for an unconventional starboard to starboard passage. Great Lakes carriers normally followed routes on the lakes that called for port-to-port side passing when they crossed paths.

Lost Grain Ship Doty Found Off Milwaukee

Divers recently found the wreck of the L. R. Doty that disappeared in a gale on Lake Michigan on October 24, 1898 with all 17 members of its crew. The 291-foot-long ship was found upright, intact and well preserved in about 300 feet of water according to divers for the Wisconsin Underwater Archaeology Association who made the discovery. The Doty, built in 1893, was among the largest wooden hulled bulk carriers operating on the lakes when it was lost only five years later. This steamer was laden with 107,000 bushels of corn and towing the schooner-barge Olive Jeanette, heading north from Chicago, when the two vessels encountered the storm off the Wisconsin coast.

Divers recently found the wreck of the L. R. Doty that disappeared in a gale on Lake Michigan on October 24, 1898 with all 17 members of its crew. The 291-foot-long ship was found upright, intact and well preserved in about 300 feet of water according to divers for the Wisconsin Underwater Archaeology Association who made the discovery. The Doty, built in 1893, was among the largest wooden hulled bulk carriers operating on the lakes when it was lost only five years later. This steamer was laden with 107,000 bushels of corn and towing the schooner-barge Olive Jeanette, heading north from Chicago, when the two vessels encountered the storm off the Wisconsin coast.

Was the Cook Murdered?

Mary Gowman, the cook on the schooner-barge Harvey Bissel was found dead of a ball shot to the chest while the vessel was on Lake Michigan, off Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, on May 10, 1882. When the boat arrived that night at Sturgeon Bay, the captain, a man identified only by the last name of Brock, contacted local authorities and an official investigation was made. It was a stormy night, the local coroner could not be located, so the justice-of-the-peace summoned a group of six citizens to serve as a jury. A suicide verdict was reached but there were some serious unanswered questions.

Mary Gowman, the cook on the schooner-barge Harvey Bissel was found dead of a ball shot to the chest while the vessel was on Lake Michigan, off Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, on May 10, 1882. When the boat arrived that night at Sturgeon Bay, the captain, a man identified only by the last name of Brock, contacted local authorities and an official investigation was made. It was a stormy night, the local coroner could not be located, so the justice-of-the-peace summoned a group of six citizens to serve as a jury. A suicide verdict was reached but there were some serious unanswered questions.

La Salle’s Griffin, First Great Lakes Ship