Ancient "Cavemen" Knew More Than We Once Thought

By James Donahue

Imagine what we might do if we could develop a time machine and suddenly get catapulted thousands of years back into the past, without prospects for a return trip. We would probably arrive stripped of all modern vestiges of contemporary life, without tools . . . possibly without the clothes we wore when we stepped into the machine. All we would possess is our intellect and our memory of the world we left behind.

We would, in effect, be cavemen and women. But even with our contemporary intellect, could we survive?

Our first task would be to find food and shelter, and to devise some kind of instruments for personal protection, for hunting, and for building. Our first home would probably be a cave and our first tasks would be to find food . . . probably nuts, berries and other natural fruits.

If possible, we would have to overpower and kill an animal, and then to prepare its hide for a personal protective coat against the environment. Could we find and identify the right kinds of stones and have the ability to chip them to fashion a sharp instrument for building a spear? And once we have the weapon, do we know how to hunt and get close enough to a wild animal to kill it? And once we have achieved this, we must somehow cut away the hide and use it to design a coat. Is the tanning of pelts a forgotten art?

Fire for heat and cooking food would be high on our list of needs, but not easy to find. Of course, we might have happened to arrive with a pack of matches in our pocket. The alternatives would be to wait for a bolt of lightning to start a forest fire, get lucky and find some flint, or remember our Boy Scout training and rub sticks to make sparks.

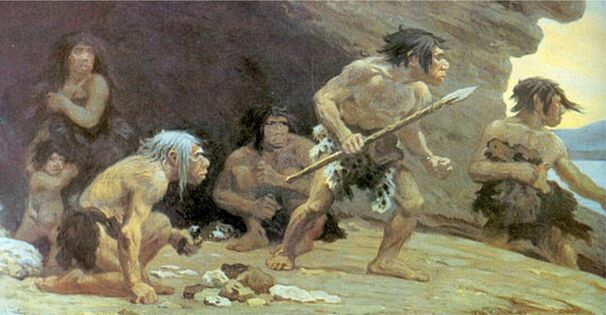

When we think of the complexities of basic survival under "caveman" conditions, there is an understanding that early humanoid primates, whether Neanderthal or homo Sapiens, were much more savvy than some historians have pictured them. They lacked the running speed to capture most wild animals and their bodies were not naturally protected by the fur of a wild animal. What they had, however, was intellect. They survived because they could make tools and outwit the animals they hunted.

It should be of no surprise, then, that an archaeological research group recently found evidence of a "beach party" among Homo sapiens in a cave near a South African coast dating to an estimated 164,000 years ago.

What they found at Pinnacle Point, overlooking the Indian Ocean, was remnants of harvested and cooked seafood, reddish pigment from ground rocks and early tiny blade technology. It is obvious that the people living in that cave understood how to steam mussels found along the nearby seashore.

Writing for the publication Nature, Curtis Marean, professor of anthropology at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, said he found not only remnants of mussels, but also small saltwater clams, sea snails and even a barnacle suggesting that whale blubber or a skin was once brought into the cave.

Marean wrote that the harvested sea food was apparently placed over hot rocks to cook. When the food was done, the shells popped open in a process very much like modern mussel-steaming. When he tried preparing mussels in this way, the process worked, he said.

Another unexpected discovery in that cave, were 57 ground-up rocks of various colors, from red to pinkish-brown, that were apparently used as cosmetics. Marean suggested that the powdered material was used for self-decoration like makeup is used today.

Yet another research team has discovered that a study of DNA from Neanderthal bones, collected from a cave in northern Spain, contained a critical gene called FOXP2, believed to play a critical role in human speech and language.

Paleogeneticist Johannes Krause, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany, told LiveScience that the finding strongly suggests that Neanderthals appear to have been capable of advanced language, just as Homo sapiens are today.

Thus the image of course, hairy, cave dwellers that carried clubs and walked around grunting and thumping their chests, seems to be something fabricated by early historians who really didn't know what they were talking about.

Humans may have been forced to dwell in caves, especially during the great ice ages that followed catastrophic events that lead to mass extinctions, but they did not lose their intellect. That intellect was what helped them survive.

By James Donahue

Imagine what we might do if we could develop a time machine and suddenly get catapulted thousands of years back into the past, without prospects for a return trip. We would probably arrive stripped of all modern vestiges of contemporary life, without tools . . . possibly without the clothes we wore when we stepped into the machine. All we would possess is our intellect and our memory of the world we left behind.

We would, in effect, be cavemen and women. But even with our contemporary intellect, could we survive?

Our first task would be to find food and shelter, and to devise some kind of instruments for personal protection, for hunting, and for building. Our first home would probably be a cave and our first tasks would be to find food . . . probably nuts, berries and other natural fruits.

If possible, we would have to overpower and kill an animal, and then to prepare its hide for a personal protective coat against the environment. Could we find and identify the right kinds of stones and have the ability to chip them to fashion a sharp instrument for building a spear? And once we have the weapon, do we know how to hunt and get close enough to a wild animal to kill it? And once we have achieved this, we must somehow cut away the hide and use it to design a coat. Is the tanning of pelts a forgotten art?

Fire for heat and cooking food would be high on our list of needs, but not easy to find. Of course, we might have happened to arrive with a pack of matches in our pocket. The alternatives would be to wait for a bolt of lightning to start a forest fire, get lucky and find some flint, or remember our Boy Scout training and rub sticks to make sparks.

When we think of the complexities of basic survival under "caveman" conditions, there is an understanding that early humanoid primates, whether Neanderthal or homo Sapiens, were much more savvy than some historians have pictured them. They lacked the running speed to capture most wild animals and their bodies were not naturally protected by the fur of a wild animal. What they had, however, was intellect. They survived because they could make tools and outwit the animals they hunted.

It should be of no surprise, then, that an archaeological research group recently found evidence of a "beach party" among Homo sapiens in a cave near a South African coast dating to an estimated 164,000 years ago.

What they found at Pinnacle Point, overlooking the Indian Ocean, was remnants of harvested and cooked seafood, reddish pigment from ground rocks and early tiny blade technology. It is obvious that the people living in that cave understood how to steam mussels found along the nearby seashore.

Writing for the publication Nature, Curtis Marean, professor of anthropology at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, said he found not only remnants of mussels, but also small saltwater clams, sea snails and even a barnacle suggesting that whale blubber or a skin was once brought into the cave.

Marean wrote that the harvested sea food was apparently placed over hot rocks to cook. When the food was done, the shells popped open in a process very much like modern mussel-steaming. When he tried preparing mussels in this way, the process worked, he said.

Another unexpected discovery in that cave, were 57 ground-up rocks of various colors, from red to pinkish-brown, that were apparently used as cosmetics. Marean suggested that the powdered material was used for self-decoration like makeup is used today.

Yet another research team has discovered that a study of DNA from Neanderthal bones, collected from a cave in northern Spain, contained a critical gene called FOXP2, believed to play a critical role in human speech and language.

Paleogeneticist Johannes Krause, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany, told LiveScience that the finding strongly suggests that Neanderthals appear to have been capable of advanced language, just as Homo sapiens are today.

Thus the image of course, hairy, cave dwellers that carried clubs and walked around grunting and thumping their chests, seems to be something fabricated by early historians who really didn't know what they were talking about.

Humans may have been forced to dwell in caves, especially during the great ice ages that followed catastrophic events that lead to mass extinctions, but they did not lose their intellect. That intellect was what helped them survive.