Was The Lady Elgin Cursed?

By James Donahue

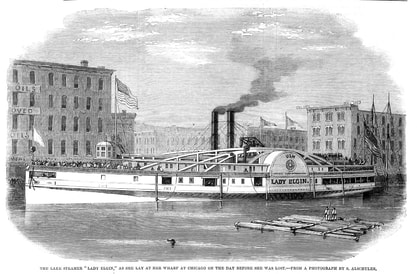

Some said the side-wheeled steamer Lady Elgin bore a curse from the day it was launched at Buffalo, New York, in 1851. That is because the engine and boilers came from the Cleopatra, an ocean slave trader that was confiscated by the U. S. Navy. But nobody dreamed that the Lady Elgin would be remembered as one of the worst disasters in Great Lakes history. When she was sunk in a collision on Lake Michigan, off Winnetka, Illinois, on September 8, 1860, an estimated two hundred eighty-seven passengers and crew members perished.

The lady was considered to have been a monster ship in her day. She measured a full two hundred fifty-two feet in length and boasted over a thousand tons of displacement, making her one of the largest vessels afloat on the lakes.

On the day of the crash, the Lady Elgin was steaming north from Chicago with about three hundred excursionists, fifty ordinary passengers and a crew of thirty-five officers and men, all bound for Milwaukee. Many of the passengers were members of the Milwaukee Light Guardsmen, the German Black Jaegers, and German Green Jaegers, who were returning from an excursion trip to Chicago. They were preparing to join Union forces in the Civil War and were in the windy city that week to raise money for guns and equipment.

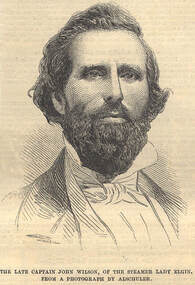

The Lady Elgin left Chicago the night of September 7, and steamed right into a thunderstorm, which by 2:00 AM developed into a full northwesterly gale. Capt. Jack Wilson wasn’t worried though. He turned the bow of his command directly into the wind and the vessel was weathering the storm well. Disaster came unexpectedly at 2:30 AM when the two-masted lumber schooner Augusta came out of the darkness to crash into the steamer’s port side.

The Augusta, under the command of Capt. Darius Malott, was sailing through the lakes from Port Huron, bound for Chicago with a heavy load of lumber. Malott later said the ship was under heavy sail when the storm struck. The crew was preoccupied with getting the sails reefed and the vessel under control when the lights of the steamer were seen off the starboard bow. Malott said he ordered the helm put hard about, but the ship didn’t answer her rudder.

Within minutes the schooner collided with the steamer, at the midships gangway just forward of the wheel, putting a large hole in the side of the Lady Elgin’s wooden hull. The Augusta quickly pulled away from the steamer and was blown off before the wind into the night, with her foresails wrecked and her bow badly crushed and leaking.

Because of the storm Malott said he couldn’t return to the scene of the collision so he continued on to Chicago where he reported the accident. He said he never dreamed the collision sank the steamer, which was more than twice the size of the Augusta. But the Lady Elgin was, indeed, fatally wounded.

Bedlam broke out on her decks as soon as people realized the steamer was sinking. The Lady Elgin was only ten miles off the Illinois coast so Wilson tried at first to run his crippled ship to shallow water. To gain time he ordered the cargo and passengers moved to the starboard side. He reasoned that if he could get the vessel to list in the other direction, he might get the hole in her port side raised above the waterline.

Wilson also sent officers below deck with blankets, mattresses and lumber, doing all they could to plug the hole that was quickly sending the elegant ship to the bottom of Lake Michigan. Nothing worked. The water soon flooded the engine room and put out the fires. The engine crew opened the steam valves to the boilers to prevent an explosion once the cold water hit them. Then came the order to abandon ship.

The Lady Elgin was sinking faster than Wilson realized and only two lifeboats got launched. It was said the ship went down about twenty minutes after the crash. Many people found themselves clinging to wreckage, mostly from the deck and upper cabins, which floated away from the hull as the ship sank under their feet. Many were still alive, hanging on to the floating debris, when the drifted close to shore. There the brutal surf, still fanned by the gale, played a lethal game of death.

Hundreds of struggling souls, now exhausted from hours of exposure to the storm-lashed lake, lacked the strength to endure this final ordeal. They were either dashed to their death on the rocks or drowned in the surf. Bodies were stacked like cordwood on the rocky coast that day. Only ninety-eight survivors were counted.

The disaster was so staggering that a stigma was attached to the Augusta from that day on. It followed the schooner everywhere. Her owners changed the vessel’s name to Colonel Cook but that did not fool anyone. She was always remembered as the schooner that sank the Lady Elgin. Malott died three years later when his next command, the bark Major, also sank in Lake Michigan. Strangely it is said the Major lies within ten miles from the Lady Elgin.

By James Donahue

Some said the side-wheeled steamer Lady Elgin bore a curse from the day it was launched at Buffalo, New York, in 1851. That is because the engine and boilers came from the Cleopatra, an ocean slave trader that was confiscated by the U. S. Navy. But nobody dreamed that the Lady Elgin would be remembered as one of the worst disasters in Great Lakes history. When she was sunk in a collision on Lake Michigan, off Winnetka, Illinois, on September 8, 1860, an estimated two hundred eighty-seven passengers and crew members perished.

The lady was considered to have been a monster ship in her day. She measured a full two hundred fifty-two feet in length and boasted over a thousand tons of displacement, making her one of the largest vessels afloat on the lakes.

On the day of the crash, the Lady Elgin was steaming north from Chicago with about three hundred excursionists, fifty ordinary passengers and a crew of thirty-five officers and men, all bound for Milwaukee. Many of the passengers were members of the Milwaukee Light Guardsmen, the German Black Jaegers, and German Green Jaegers, who were returning from an excursion trip to Chicago. They were preparing to join Union forces in the Civil War and were in the windy city that week to raise money for guns and equipment.

The Lady Elgin left Chicago the night of September 7, and steamed right into a thunderstorm, which by 2:00 AM developed into a full northwesterly gale. Capt. Jack Wilson wasn’t worried though. He turned the bow of his command directly into the wind and the vessel was weathering the storm well. Disaster came unexpectedly at 2:30 AM when the two-masted lumber schooner Augusta came out of the darkness to crash into the steamer’s port side.

The Augusta, under the command of Capt. Darius Malott, was sailing through the lakes from Port Huron, bound for Chicago with a heavy load of lumber. Malott later said the ship was under heavy sail when the storm struck. The crew was preoccupied with getting the sails reefed and the vessel under control when the lights of the steamer were seen off the starboard bow. Malott said he ordered the helm put hard about, but the ship didn’t answer her rudder.

Within minutes the schooner collided with the steamer, at the midships gangway just forward of the wheel, putting a large hole in the side of the Lady Elgin’s wooden hull. The Augusta quickly pulled away from the steamer and was blown off before the wind into the night, with her foresails wrecked and her bow badly crushed and leaking.

Because of the storm Malott said he couldn’t return to the scene of the collision so he continued on to Chicago where he reported the accident. He said he never dreamed the collision sank the steamer, which was more than twice the size of the Augusta. But the Lady Elgin was, indeed, fatally wounded.

Bedlam broke out on her decks as soon as people realized the steamer was sinking. The Lady Elgin was only ten miles off the Illinois coast so Wilson tried at first to run his crippled ship to shallow water. To gain time he ordered the cargo and passengers moved to the starboard side. He reasoned that if he could get the vessel to list in the other direction, he might get the hole in her port side raised above the waterline.

Wilson also sent officers below deck with blankets, mattresses and lumber, doing all they could to plug the hole that was quickly sending the elegant ship to the bottom of Lake Michigan. Nothing worked. The water soon flooded the engine room and put out the fires. The engine crew opened the steam valves to the boilers to prevent an explosion once the cold water hit them. Then came the order to abandon ship.

The Lady Elgin was sinking faster than Wilson realized and only two lifeboats got launched. It was said the ship went down about twenty minutes after the crash. Many people found themselves clinging to wreckage, mostly from the deck and upper cabins, which floated away from the hull as the ship sank under their feet. Many were still alive, hanging on to the floating debris, when the drifted close to shore. There the brutal surf, still fanned by the gale, played a lethal game of death.

Hundreds of struggling souls, now exhausted from hours of exposure to the storm-lashed lake, lacked the strength to endure this final ordeal. They were either dashed to their death on the rocks or drowned in the surf. Bodies were stacked like cordwood on the rocky coast that day. Only ninety-eight survivors were counted.

The disaster was so staggering that a stigma was attached to the Augusta from that day on. It followed the schooner everywhere. Her owners changed the vessel’s name to Colonel Cook but that did not fool anyone. She was always remembered as the schooner that sank the Lady Elgin. Malott died three years later when his next command, the bark Major, also sank in Lake Michigan. Strangely it is said the Major lies within ten miles from the Lady Elgin.