Solving The Mystery Of The Three Hares

By James Donahue

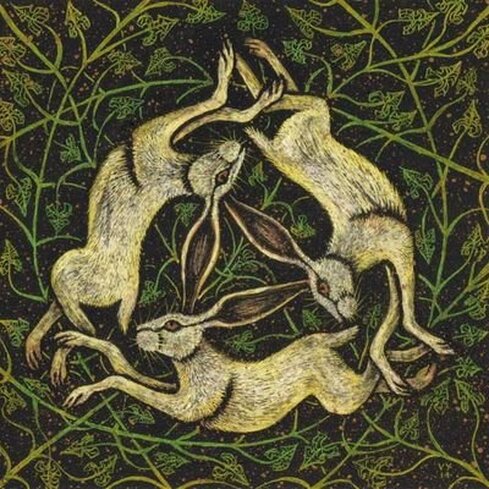

A team of British researchers recently traveled to Dunhuang, China, in an attempt to find the answer to a riddle involving an ancient symbol of the three hares, found in sacred shrines and temples from Britain, throughout Europe, the Middle East and Far East. The depictions of the three hares joined at the ears and chasing each other are mysteriously found in holy buildings from Buddhist, Islamic and Christian faiths by people separated by five thousand miles and over a thousand years.

The earliest known depictions of the hares date back to the Chinese Sui dynasty from the years 589-618. They are found painted in textile canopies painted on the ceilings of caves at Dunhuang. The town is famous for the network of caves, discovered by British explorer Marc Aurel Stein sometime before 1930. The caves were found sealed and containing thousands of well-preserved documents and fabrics from the old Silk Road. Historians and archaeologists believe the Silk Road, the ancient route by which silk fabrics were transported from China through the Middle East and into Europe, is an important link to the origin of the three hare’s art. Some believe the symbol has its origins in China, and from there it was brought west into Europe. The hares are found in religious structures all along the old Silk Road, and nowhere else. Not only are they carved in wood in medieval churches, but the image has been hammered out in Thirteenth Century Mongol metal work, placed in window frames, and even set in stained glass.

The researchers are looking not only for the history of the three hare’s motif, but its esoteric and/or sacred meaning. They are especially curious why the image appears in religious shrines of three different faiths. At Devon, England, where some seventeen known churches are known to contain the image in some form, archaeologist Dr. Tom Greeves believes the symbol had a special meaning that was known when the structures were built over three hundred years ago, although it has been since forgotten. “We can deduce from the motif’s use in holy places in different religions and cultures, and the prominence it was given, that the symbol had a special significance. Until recently there has been little awareness of its wide distribution. We are uncovering new examples all the time,” Greeves said. The link between the Christian churches of England and the old Silk Road is probably best shown in Exeter Cathedral where is found a painting of Bishop Walter Bronescombe with a representation of an oriental textile. The bishop died in 1280.

The fact that the three hare image appears in buildings along the old route, where the highly prized silk textiles were carried from the Orient into the known western world, is only recently known. During the medieval period the silk textures, many woven with gold threat, were used in the churches for wrapping holy relics, as altar cloths, palls for shrines and even as linings in holy books. The hare in some native cultures carries both divine and mystical qualities. African people regarded this animal as a trickster, just as Native Americans in the Southwestern United States regard the coyote. Other cultures see a pattern of craters on the moon as the image of a hare. Also the constellation Lepus represents a hare. Thus the animal has played an important part in native folk lore and beliefs all over the world.

That there are always three hares links us to numerology. In Christianity there is a natural tie with the number three in the Trinity of God. That the hare is well known as an image of fertility, especially at Easter, also could give us a sexual connotation. The union of two creates a third. Other sacred concepts of three: the beginning, middle and end; past, present and future; and body, mind and spirit. The third Tarot card is the Empress. This card, like the image of the hare, offers the concept of fertility and motherhood. The card expresses a love of the earth and the nourishment of life. The Empress is luxuriating in plenty and receiving a lavish reward. She is connected with the earth and in harmony with its natural rhythms. Crowley attributed the Empress to the Fourteenth Path on the Tree of Life, between Chokmah (the Father) and Binah (the Mother). A gold triangle at the top of her throne on the Crowley card represents the Supernal Triangle: Kether, Chokmah and Binah.

The imagery on the Crowley card is especially significant. She is seated on a scroll that represents the divine law, or a manifestation of the Word of God. Through the magic of mothering, force, or Chokmah is represented as sacred structures of spirit. At the feet of the Empress are green waves of vegetation. Also there is a crescent moon and streams from it, indicating the beginning of the stream of consciousness into the world.

By James Donahue

A team of British researchers recently traveled to Dunhuang, China, in an attempt to find the answer to a riddle involving an ancient symbol of the three hares, found in sacred shrines and temples from Britain, throughout Europe, the Middle East and Far East. The depictions of the three hares joined at the ears and chasing each other are mysteriously found in holy buildings from Buddhist, Islamic and Christian faiths by people separated by five thousand miles and over a thousand years.

The earliest known depictions of the hares date back to the Chinese Sui dynasty from the years 589-618. They are found painted in textile canopies painted on the ceilings of caves at Dunhuang. The town is famous for the network of caves, discovered by British explorer Marc Aurel Stein sometime before 1930. The caves were found sealed and containing thousands of well-preserved documents and fabrics from the old Silk Road. Historians and archaeologists believe the Silk Road, the ancient route by which silk fabrics were transported from China through the Middle East and into Europe, is an important link to the origin of the three hare’s art. Some believe the symbol has its origins in China, and from there it was brought west into Europe. The hares are found in religious structures all along the old Silk Road, and nowhere else. Not only are they carved in wood in medieval churches, but the image has been hammered out in Thirteenth Century Mongol metal work, placed in window frames, and even set in stained glass.

The researchers are looking not only for the history of the three hare’s motif, but its esoteric and/or sacred meaning. They are especially curious why the image appears in religious shrines of three different faiths. At Devon, England, where some seventeen known churches are known to contain the image in some form, archaeologist Dr. Tom Greeves believes the symbol had a special meaning that was known when the structures were built over three hundred years ago, although it has been since forgotten. “We can deduce from the motif’s use in holy places in different religions and cultures, and the prominence it was given, that the symbol had a special significance. Until recently there has been little awareness of its wide distribution. We are uncovering new examples all the time,” Greeves said. The link between the Christian churches of England and the old Silk Road is probably best shown in Exeter Cathedral where is found a painting of Bishop Walter Bronescombe with a representation of an oriental textile. The bishop died in 1280.

The fact that the three hare image appears in buildings along the old route, where the highly prized silk textiles were carried from the Orient into the known western world, is only recently known. During the medieval period the silk textures, many woven with gold threat, were used in the churches for wrapping holy relics, as altar cloths, palls for shrines and even as linings in holy books. The hare in some native cultures carries both divine and mystical qualities. African people regarded this animal as a trickster, just as Native Americans in the Southwestern United States regard the coyote. Other cultures see a pattern of craters on the moon as the image of a hare. Also the constellation Lepus represents a hare. Thus the animal has played an important part in native folk lore and beliefs all over the world.

That there are always three hares links us to numerology. In Christianity there is a natural tie with the number three in the Trinity of God. That the hare is well known as an image of fertility, especially at Easter, also could give us a sexual connotation. The union of two creates a third. Other sacred concepts of three: the beginning, middle and end; past, present and future; and body, mind and spirit. The third Tarot card is the Empress. This card, like the image of the hare, offers the concept of fertility and motherhood. The card expresses a love of the earth and the nourishment of life. The Empress is luxuriating in plenty and receiving a lavish reward. She is connected with the earth and in harmony with its natural rhythms. Crowley attributed the Empress to the Fourteenth Path on the Tree of Life, between Chokmah (the Father) and Binah (the Mother). A gold triangle at the top of her throne on the Crowley card represents the Supernal Triangle: Kether, Chokmah and Binah.

The imagery on the Crowley card is especially significant. She is seated on a scroll that represents the divine law, or a manifestation of the Word of God. Through the magic of mothering, force, or Chokmah is represented as sacred structures of spirit. At the feet of the Empress are green waves of vegetation. Also there is a crescent moon and streams from it, indicating the beginning of the stream of consciousness into the world.