Can A Curse Engraved In Stone Bring Bad Luck?

By James Donahue

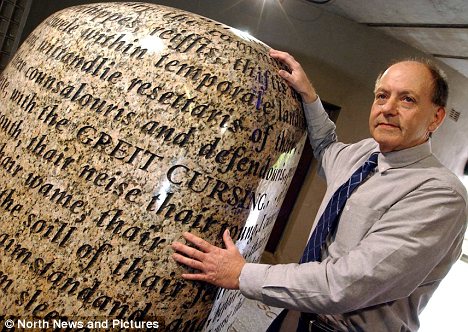

In 2001 the City of Carlisle, England, paid 10,000 pounds to have an artist design and make a 14-ton granite slab to mark the town’s Millennium Gateway scheme. It was installed as the centerpiece of an underground gallery in the Tullie House Museum of historical relics.

In historical retrospect, the slab was engraved with a 1,069-word curse, issued by the Archbishop of Glasgow, Scotland, in 1524. The curse was an effort to keep the plundering Scots from raiding Carlisle, located just over the Scottish border.

After the slab was installed, Carlisle began experiencing a string of disastrous events that some people blamed on the curse. The town’s bakery burned down, there was an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease among the area livestock, the community suffered the worst local flood in more than a century, there was a rash of local factories closed and jobs lost, and the town’s football team lost so many games it was relegated from the area football league.

Things got so bad the town fathers began debating whether the curse on the stone was actually the cause of so much ill fortune. The media began calling the piece the Carlisle Cursing Stone.

Councilor Jim Tootle proposed that the stone be destroyed or at least moved outside the city boundaries. “The curse was laid in a serious fashion and it should be taken seriously. I’ve had phone calls from people concerned that this curse should be removed,” he said.

Tootle said that some folks believed that “the placing of a non-Christian artifact, based on an old curse on local families, would bring ill luck to the city.”

Vicar Kevin Davies wrote in his parish magazine that he thought the stone was “a lethal weapon” and called for the curse to be broken “both literally and spiritually for all time.”

But local artist Gordon Young, a descendant of one of the “reviver families” accused of raiding the town in the old times, objected. “They want to smash it to pieces,” he said. “It is a powerful work of art but it is certainly not part of the occult. If I thought my sculpture would have affected one Carlisle United result, I would have smashed it myself years ago.”

The Carlisle United is the name of the local football team. Never mind that three local people perished in the flood.

After much debate, the town fathers couldn’t muster enough votes to destroy the stone and it still remains in place at the museum. But the issue may not be over.

In the meantime, the council has asked Archbishop Mario Conti of Glasgow to lift the old curse, just in case it really is true.

A spokesman for the church said “the Archbishop would consider carefully any representation made to him by the civic or religious authorities in Carlisle.”

So we don’t know if he did or did not lift the curse. Perhaps he didn’t know how, since Christian cursing is not something done much these days.

By James Donahue

In 2001 the City of Carlisle, England, paid 10,000 pounds to have an artist design and make a 14-ton granite slab to mark the town’s Millennium Gateway scheme. It was installed as the centerpiece of an underground gallery in the Tullie House Museum of historical relics.

In historical retrospect, the slab was engraved with a 1,069-word curse, issued by the Archbishop of Glasgow, Scotland, in 1524. The curse was an effort to keep the plundering Scots from raiding Carlisle, located just over the Scottish border.

After the slab was installed, Carlisle began experiencing a string of disastrous events that some people blamed on the curse. The town’s bakery burned down, there was an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease among the area livestock, the community suffered the worst local flood in more than a century, there was a rash of local factories closed and jobs lost, and the town’s football team lost so many games it was relegated from the area football league.

Things got so bad the town fathers began debating whether the curse on the stone was actually the cause of so much ill fortune. The media began calling the piece the Carlisle Cursing Stone.

Councilor Jim Tootle proposed that the stone be destroyed or at least moved outside the city boundaries. “The curse was laid in a serious fashion and it should be taken seriously. I’ve had phone calls from people concerned that this curse should be removed,” he said.

Tootle said that some folks believed that “the placing of a non-Christian artifact, based on an old curse on local families, would bring ill luck to the city.”

Vicar Kevin Davies wrote in his parish magazine that he thought the stone was “a lethal weapon” and called for the curse to be broken “both literally and spiritually for all time.”

But local artist Gordon Young, a descendant of one of the “reviver families” accused of raiding the town in the old times, objected. “They want to smash it to pieces,” he said. “It is a powerful work of art but it is certainly not part of the occult. If I thought my sculpture would have affected one Carlisle United result, I would have smashed it myself years ago.”

The Carlisle United is the name of the local football team. Never mind that three local people perished in the flood.

After much debate, the town fathers couldn’t muster enough votes to destroy the stone and it still remains in place at the museum. But the issue may not be over.

In the meantime, the council has asked Archbishop Mario Conti of Glasgow to lift the old curse, just in case it really is true.

A spokesman for the church said “the Archbishop would consider carefully any representation made to him by the civic or religious authorities in Carlisle.”

So we don’t know if he did or did not lift the curse. Perhaps he didn’t know how, since Christian cursing is not something done much these days.