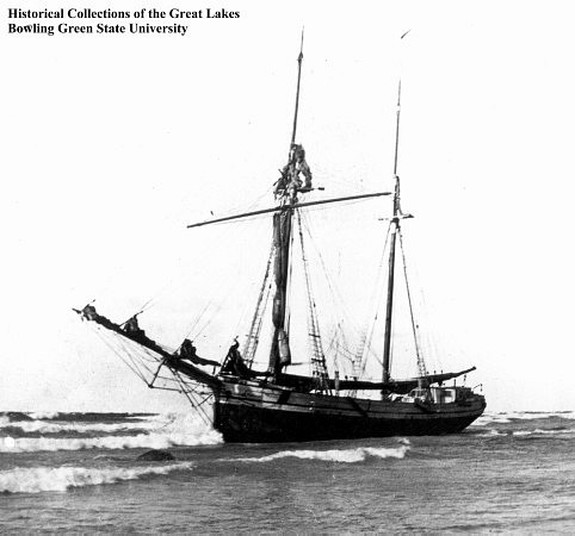

Jupiter

The Jupiter And Saturn

By James Donahue

They bore the names of planets but the Jupiter and Saturn were just ordinary working schooner-barges in the business of hauling iron ore. After the late November storm of 1872 the names were marred because they sank together taking the lives of 15 sailors.

The tragedy on Lake Superior helped bring about the construction of four new government life-saving stations on the Northern Michigan shoreline.

The Jupiter and Saturn were two of several vessels lost in the same storm, and their crews were among many sailors who drowned. That they were lost together, and that the crew of the steam barge John A. Dix, which had them in tow, lived to tell the story, helped dramatize the sinkings.

Captain Joseph Waltman, master of the Dix, said the three vessels left Marquette, Michigan, at 3:30 p.m. on Tuesday. The Dix, a retired government revenue ship, was purchased that season by E. B. Ward of Detroit for use as a tug. The two barges were each laden with about four hundred and sixteen tons of iron ore, bound for Wyandotte, Michigan.

At first there was a light breeze blowing from the southeast and Waltman said that even though it was late in November, the weather was pleasant. When a light head wind developed that night, Captain Peter Howard, master of the Jupiter, and Captain Richard Stringleman, skipper of the Saturn, reefed the barge sails because they were no longer helping the Dix. By then the sky was overcast and it had started snowing.

At about 4 a.m. the wind veered to the northwest. Waltman said he noticed the barges were both under full sail again. He said he felt that the trip was going so well, and the barges were making such good time he thought they would make Sault Ste. Marie within a few hours.

What Waltman didn’t know as he entertained those thoughts, was that an ugly winter gale was bearing down on the three boats. It was coming with such speed and force that within the next 20 minutes the crews of all three vessels would be in a battle for their lives.

Waltman said the storm hit with such power it parted the tow cable to the Jupiter almost immediately. The Saturn broke away and drifted off into the gale at about 6 a.m. The storm front blasted the boats with heavy snow, high winds and fast dropping temperatures. Within a short time the thermometers were reading below zero degrees and at one point the gauges recorded temperatures at minus eighteen degrees. Layers of ice were building on the decks of the boats.

Waltman said the Dix was in such a fight for its own survival he couldn’t think about turning around to save the barges. He said both vessels were provided with good sails and experienced crew members. They had pumps and lifeboats. Thus Waltman reasoned that the men in the barges were on their own.

By the time the Dix steamed to the lee side of Whitefish Point, the decks were coated with about a foot of ice. The crew used salt to help chip it away before the steamer continued on to Sault Ste. Marie.

While under the protection of the point, Waltman said everybody kept an eye out for the Jupiter and Saturn, hoping they would catch up with the Dix. But the two schooners never arrived. The steamer China later reported seeing the masts of the Saturn where it sank about three miles above Whitefish Point. The spars of the Jupiter were found twelve miles west of there. Nobody will ever know what the crews of those two vessels endured before they perished.

In the spring the bodies of two sailors were found on the beach. It was evident that they reached shore and crawled a few hundred feet out of the weather before freezing to death. The area was uninhabited and the men had no chance of finding shelter.

The Dix didn’t reach Sault Ste. Marie until the following spring. The ship was one of a fleet of steamers and barges caught in the offshore ice that week. The high winds and sub-zero temperatures brought an abrupt end to the shipping season and caught many vessels still out of port.

By James Donahue

They bore the names of planets but the Jupiter and Saturn were just ordinary working schooner-barges in the business of hauling iron ore. After the late November storm of 1872 the names were marred because they sank together taking the lives of 15 sailors.

The tragedy on Lake Superior helped bring about the construction of four new government life-saving stations on the Northern Michigan shoreline.

The Jupiter and Saturn were two of several vessels lost in the same storm, and their crews were among many sailors who drowned. That they were lost together, and that the crew of the steam barge John A. Dix, which had them in tow, lived to tell the story, helped dramatize the sinkings.

Captain Joseph Waltman, master of the Dix, said the three vessels left Marquette, Michigan, at 3:30 p.m. on Tuesday. The Dix, a retired government revenue ship, was purchased that season by E. B. Ward of Detroit for use as a tug. The two barges were each laden with about four hundred and sixteen tons of iron ore, bound for Wyandotte, Michigan.

At first there was a light breeze blowing from the southeast and Waltman said that even though it was late in November, the weather was pleasant. When a light head wind developed that night, Captain Peter Howard, master of the Jupiter, and Captain Richard Stringleman, skipper of the Saturn, reefed the barge sails because they were no longer helping the Dix. By then the sky was overcast and it had started snowing.

At about 4 a.m. the wind veered to the northwest. Waltman said he noticed the barges were both under full sail again. He said he felt that the trip was going so well, and the barges were making such good time he thought they would make Sault Ste. Marie within a few hours.

What Waltman didn’t know as he entertained those thoughts, was that an ugly winter gale was bearing down on the three boats. It was coming with such speed and force that within the next 20 minutes the crews of all three vessels would be in a battle for their lives.

Waltman said the storm hit with such power it parted the tow cable to the Jupiter almost immediately. The Saturn broke away and drifted off into the gale at about 6 a.m. The storm front blasted the boats with heavy snow, high winds and fast dropping temperatures. Within a short time the thermometers were reading below zero degrees and at one point the gauges recorded temperatures at minus eighteen degrees. Layers of ice were building on the decks of the boats.

Waltman said the Dix was in such a fight for its own survival he couldn’t think about turning around to save the barges. He said both vessels were provided with good sails and experienced crew members. They had pumps and lifeboats. Thus Waltman reasoned that the men in the barges were on their own.

By the time the Dix steamed to the lee side of Whitefish Point, the decks were coated with about a foot of ice. The crew used salt to help chip it away before the steamer continued on to Sault Ste. Marie.

While under the protection of the point, Waltman said everybody kept an eye out for the Jupiter and Saturn, hoping they would catch up with the Dix. But the two schooners never arrived. The steamer China later reported seeing the masts of the Saturn where it sank about three miles above Whitefish Point. The spars of the Jupiter were found twelve miles west of there. Nobody will ever know what the crews of those two vessels endured before they perished.

In the spring the bodies of two sailors were found on the beach. It was evident that they reached shore and crawled a few hundred feet out of the weather before freezing to death. The area was uninhabited and the men had no chance of finding shelter.

The Dix didn’t reach Sault Ste. Marie until the following spring. The ship was one of a fleet of steamers and barges caught in the offshore ice that week. The high winds and sub-zero temperatures brought an abrupt end to the shipping season and caught many vessels still out of port.