Living Among The Dead And The Dying

By James Donahue

The newspaper I worked for at Benton Harbor, Michigan, in the early journalism years, used as much art as possible to tell the stories of major news events in our area. That meant publishing photographs of every local person killed in traffic accidents, drowning, shootings, and worst-of-all, the Vietnam War.

We also attempted to get pictures of every fatal traffic accident and every violent death scene. Consequently I was always on police call. It was rare when I didn’t spent a Saturday night shooting pictures of tangled wreckage on some highway. I lived with my camera, a standard Speed Graphic that shot great images on large sheets of film measuring four inches by five inches.

During the years I worked on the newspaper’s South Haven bureau, I witnessed some extremely gory scenes. And sometimes I photographed dead people without realizing it. One night while at a multiple-car crash scene on the notorious Dead Man’s Curve, a well-known place along the old Blue Star Memorial Highway in Allegan County, I was working in almost total darkness and focusing on the lights from police flashlights in an attempt to get my pictures. The next morning after my film was developed, my editor informed me that I got a great picture of the wreck. The only problem, he said, was that a dead body was hanging halfway out of it.

While we published wreck pictures, we drew the line on dead bodies. We published pictures of people still trapped inside of wrecks as long as they were still alive. I always thought pictures of suffering and still living people was worse than pictures of dead bodies. But that was just my personal opinion after years of being at the scenes and hearing the screams of the still living as they were being cut out of wreckage. The dead were just that, the dead. The suffering was over for them.

I was at drowning scenes and saw the bodies after rescue workers dragged them out of lakes, gravel pits and holes in the ice where snowmobiles had fallen through. I saw the bodies of people who froze to death. I remember one man found frozen solid while seated upright along a highway near Bangor, Michigan. He looked more like a stone statue than the body of a real human being.

Always when the victim of a fatal crash, drowning, or other terrible event lived within our reading area, the rule was that I was to attempt to get a portrait of the person to appear with the story. That was the hardest part of my job. I had to go to the home of the victim, knock on the door and ask for that picture.

I found that the best time to go to those homes was as soon as possible after the police came to give the survivors the dreadful news. People were always in a state of shock and disbelief and often gave up those treasured photographs without thinking. I sometimes wondered if they didn’t think I also was an authority figure and that giving up the picture was required of them. Sometimes the pictures were lifted right off of the television set or some other piece of furniture in the home and I knew they may be the best and only image in existence. I treated those pictures with great respect. I often drove them personally to the newspaper office, waited until the image was copied by our photography department, and then returned the picture directly to the place where I got it. I made sure the pictures were always returned.

I remember one case when two little boys got their hands on a loaded revolver and one boy shot the other to death. It happened at some remote rural location that was extremely hard to find. Once I found the house, the parents of the child informed me that they had one picture but would not part with it. They agreed, after some coaxing, to let me photograph the picture.

Fortunately I had some training in photo copying and had just the camera to do it. That big Speed Graphic camera could be opened in the back for precise focusing on objects like the picture of a little boy. I remember that I propped the picture up against a wall, set the camera carefully on some books so that it would not jiggle, opened the back and carefully focused. Instead of using a flash I brought extra lamps up close and set my F-stop for available light. Because I knew I was only going to have one chance at it, I shot several pictures, resetting my shutter speed and camera lens. It worked. I got some very good pictures while working under extremely uncomfortable conditions in a house full of mourning people.

Finding some of those homes in Allegan and Van Buren Counties was sometimes strange. The roads all had names, but there were few road markers once you left the main highways. Consequently people would give directions by saying: “Go three and a half miles north, then east four miles, then south a quarter mile. We are the first house on the left.” Directions like that usually always worked.

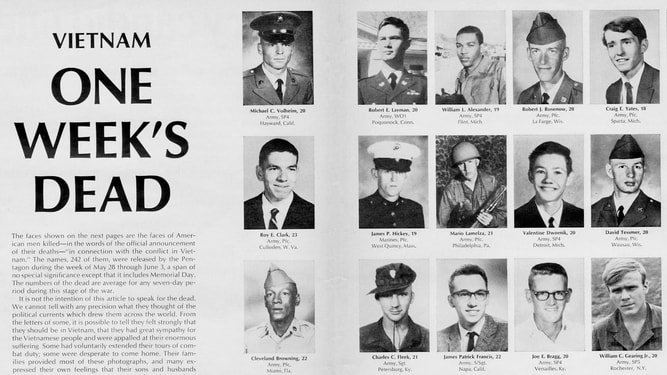

After Lyndon Johnson became president, the Vietnam War escalated and they began bringing a lot of American soldiers home in body bags. There was rarely a week that passed that I didn’t have to knock on somebody’s door in my area and ask for a picture of a war casualty. Before that ugly war came to an end, there were few people who hadn’t lost a loved one, a friend, or at least knew someone in their neighborhood who lost a son or husband in battle. Over 58,000 U.S. soldiers were killed in that war.

Getting pictures of dead soldiers was much harder to do than following police to the door after a fatal car crash. People were notified long before I got there, the shock of the moment had passed, and the images I sought were recognized as something the wives, mothers and relatives were not willing to hand off to a stranger. It took special finesse to coax those pictures from those hands. I was so moved by the grief expressed by some families that I occasionally found myself crying with them in their kitchens. I have always hated the concept of war. The Vietnam conflict was so ugly that the experience of grieving with the families of dead American soldiers hardened my heart even more to ever sending our finest young people off to die in useless combat. I also was keenly aware that but for a head injury sustained in a bad wreck in my college days, I might also have been a death count of that senseless war instead of staying behind to write about the dead.

By James Donahue

The newspaper I worked for at Benton Harbor, Michigan, in the early journalism years, used as much art as possible to tell the stories of major news events in our area. That meant publishing photographs of every local person killed in traffic accidents, drowning, shootings, and worst-of-all, the Vietnam War.

We also attempted to get pictures of every fatal traffic accident and every violent death scene. Consequently I was always on police call. It was rare when I didn’t spent a Saturday night shooting pictures of tangled wreckage on some highway. I lived with my camera, a standard Speed Graphic that shot great images on large sheets of film measuring four inches by five inches.

During the years I worked on the newspaper’s South Haven bureau, I witnessed some extremely gory scenes. And sometimes I photographed dead people without realizing it. One night while at a multiple-car crash scene on the notorious Dead Man’s Curve, a well-known place along the old Blue Star Memorial Highway in Allegan County, I was working in almost total darkness and focusing on the lights from police flashlights in an attempt to get my pictures. The next morning after my film was developed, my editor informed me that I got a great picture of the wreck. The only problem, he said, was that a dead body was hanging halfway out of it.

While we published wreck pictures, we drew the line on dead bodies. We published pictures of people still trapped inside of wrecks as long as they were still alive. I always thought pictures of suffering and still living people was worse than pictures of dead bodies. But that was just my personal opinion after years of being at the scenes and hearing the screams of the still living as they were being cut out of wreckage. The dead were just that, the dead. The suffering was over for them.

I was at drowning scenes and saw the bodies after rescue workers dragged them out of lakes, gravel pits and holes in the ice where snowmobiles had fallen through. I saw the bodies of people who froze to death. I remember one man found frozen solid while seated upright along a highway near Bangor, Michigan. He looked more like a stone statue than the body of a real human being.

Always when the victim of a fatal crash, drowning, or other terrible event lived within our reading area, the rule was that I was to attempt to get a portrait of the person to appear with the story. That was the hardest part of my job. I had to go to the home of the victim, knock on the door and ask for that picture.

I found that the best time to go to those homes was as soon as possible after the police came to give the survivors the dreadful news. People were always in a state of shock and disbelief and often gave up those treasured photographs without thinking. I sometimes wondered if they didn’t think I also was an authority figure and that giving up the picture was required of them. Sometimes the pictures were lifted right off of the television set or some other piece of furniture in the home and I knew they may be the best and only image in existence. I treated those pictures with great respect. I often drove them personally to the newspaper office, waited until the image was copied by our photography department, and then returned the picture directly to the place where I got it. I made sure the pictures were always returned.

I remember one case when two little boys got their hands on a loaded revolver and one boy shot the other to death. It happened at some remote rural location that was extremely hard to find. Once I found the house, the parents of the child informed me that they had one picture but would not part with it. They agreed, after some coaxing, to let me photograph the picture.

Fortunately I had some training in photo copying and had just the camera to do it. That big Speed Graphic camera could be opened in the back for precise focusing on objects like the picture of a little boy. I remember that I propped the picture up against a wall, set the camera carefully on some books so that it would not jiggle, opened the back and carefully focused. Instead of using a flash I brought extra lamps up close and set my F-stop for available light. Because I knew I was only going to have one chance at it, I shot several pictures, resetting my shutter speed and camera lens. It worked. I got some very good pictures while working under extremely uncomfortable conditions in a house full of mourning people.

Finding some of those homes in Allegan and Van Buren Counties was sometimes strange. The roads all had names, but there were few road markers once you left the main highways. Consequently people would give directions by saying: “Go three and a half miles north, then east four miles, then south a quarter mile. We are the first house on the left.” Directions like that usually always worked.

After Lyndon Johnson became president, the Vietnam War escalated and they began bringing a lot of American soldiers home in body bags. There was rarely a week that passed that I didn’t have to knock on somebody’s door in my area and ask for a picture of a war casualty. Before that ugly war came to an end, there were few people who hadn’t lost a loved one, a friend, or at least knew someone in their neighborhood who lost a son or husband in battle. Over 58,000 U.S. soldiers were killed in that war.

Getting pictures of dead soldiers was much harder to do than following police to the door after a fatal car crash. People were notified long before I got there, the shock of the moment had passed, and the images I sought were recognized as something the wives, mothers and relatives were not willing to hand off to a stranger. It took special finesse to coax those pictures from those hands. I was so moved by the grief expressed by some families that I occasionally found myself crying with them in their kitchens. I have always hated the concept of war. The Vietnam conflict was so ugly that the experience of grieving with the families of dead American soldiers hardened my heart even more to ever sending our finest young people off to die in useless combat. I also was keenly aware that but for a head injury sustained in a bad wreck in my college days, I might also have been a death count of that senseless war instead of staying behind to write about the dead.