The Brother Jonathan Treasure Trove

By James Donahue

When the steamship Brother Jonathan set its course on July 28, 1865, from the gold fields of San Francisco for Portland, Oregon, it was carrying a fortune in gold coins. But it was also a damaged ship that had been improperly patched, and was foolishly overloaded with cargo and passengers before it was sent out to sea in a gale.

Thus the Brother Jonathan was destined to wreck. The gale that developed the following day stressed the 13-year-old hull and an uncharted reef off the coast of Crescent City, California, doomed the ship and all but 19 of her 244 passengers and crew members to a watery grave.

The discovery of the remains of the steamer by a dive research team in 1993 sparked a long legal battle and the State of California over ownership of the rare minted gold coins that eventually brought $5.3 million in auction. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court before it was unanimously decided in favor of the finders.

The Brother Jonathan was built at the shipyards of Perrine, Patterson and Stack at Williamsburg, N.Y., in 1850 for New York businessman Edward Mills. He placed the ship the following year on a regular run, carrying passengers in the great gold rush from New York to Chagres, the old name for Colon, Panama, on their way to San Francisco.

The Panama Canal did not exist yet so people who took that route had to travel by foot or mule through the jungle to Panama, where they took another ship to Panama. It was one of three routes to go in those days. The options were to hop a clipper ship for a long trip around Cape Horn, South America, or travel my wagon across country.

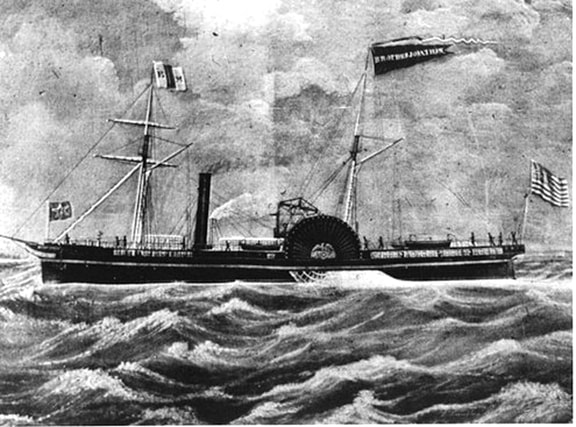

The Brother Jonathan measured 220 feet in length. It had a superstructure of upper and lower decks and boasted two 70-foot salons decorated with gilt and enamel. She was driven by two massive side-mounted paddle wheels driven by a vertical beam engine. She also was rigged as a modified two-masted barkentine.

Artist’s drawings show the ship with a single stack forward of the sidewheels. It was said that the bow was ornamented with trail boards and a billet head. The hull was black with blue wale and buff deckhouses. The wheel boxes were done in black and red, with gilt eagles painted on the side panels. A gilded eagle also appeared on the stern.

Shipbuilders of that day took pride in their craft, and turned out fine workmanship. The New York Herald on Nov. 27, 1850, on reporting the launching of the ship, described the construction of the hull as follows:

“Her floors are solid, 14 inches in depth, bolted together with one and three-quarter inch iron; five keelsons and head pieces cadged and bolted to the solid floor. The frame, at the turn of the bilge, is peculiar for its great strength, being additionally secured by strong iron diagonal braces, forming a perfect network from stem to stern; over which is laid yellow pine blanking from five to eight inches thick and all square fastened. The decks are of the most substantial description, being thoroughly secured with lodging and hanging knees. The outside if planked with white oak, and well tree nailed and copper fastened.”

That was how the Brother Jonathan looked when it was new. The vessel went through two major refittings during its years on the high seas. After a long trip from New York to San Francisco around the horn, the vessel was sold to new owners who put it on a regular run from San Francisco to Portland.

She was still on that run in July, 1865 when it was wrecked on an uncharted reef, now known as Jonathan Rock. The steamer had a new master, identified as Captain DeWolf, who took command in June of that year.

The Brother Jonathan was involved in a collision with the barkentine Jane Falkenberg while on the Columbia River. Captain DeWolf brought the ship back to San Francisco where he expected it to be put in dry dock for proper repair of the damaged hull. But the owners, anxious to avoid a lengthy delay in the middle of a busy and profitable shipping season, ordered makeshift repairs at the dock.

Next the company’s agent stacked the holds and decks with so much cargo that Captain DeWolf objected. He complained that it was too dangerous to sail the steamer in that condition. The agent warned that if DeWolf refused to take the vessel out, he would find another captain who would.

The cargo for that fateful trip included crates of $20 gold pieces, an estimated $200,000 to pay the troops at Fort Vancouver, Walla Walla, and other posts in the Northwest. It was believed that gold coins also were earmarked for an annual treaty payment for the Indian tribes and that other gold was destined for private transfers.

The ship was so heavily laden that its hull was embedded in the mud at the dock. The departure was delayed until high tide, when tugs helped pull it free and out to sea. The steamer was riding low in the water as it sluggishly pushed its way through the Golden Gate and turned north into a strong headwind and heavy seas. On board were 190 passengers and 54 crew members.

The Brother Jonathan called briefly at Crescent City to offload cargo at about 2 a.m. the next day. By mid-morning it was back to sea, battling a developing gale in an effort to clear St. George’s Reef. Captain DeWolf soon decided to turn the ship around and run back to Crescent City to wait out the storm.

When about four miles from the coast, the steamer struck the rock. The force of the moving ship, the wind and the seas first penetrated the oak hull, then tore at the bottom of the ship. DeWolf ordered everyone aft to “try and save themselves.”

Attempts to launch the ship’s lifeboats ended in disaster. The first lowered boat capsized immediately. The second boat, full of women, was being lowered astern of the paddle wheels when a giant wave smashed the boat into the side of the ship. The crew managed to get the passengers back on the Jonathan before the boat was smashed to pieces under their feet.

The only boat to get away safely was a wooden surfboat, commanded by Third Mate Patterson. With him were 10 other crew members, five women and three children. They just got away safely when the Jonathan sank by the bow, carrying everyone else down with it. They were the only survivors.

The storm prevented any rescue attempts from land that day. Bodies and wreckage floated ashore for several weeks after that.

For years after that, the story was told about the wreck of the Brother Jonathan and its lost gold treasure chests. Coin collectors were especially interested in the wreck because it was said to have carried rare Liberty gold coins minted in 1865 at the San Francisco Mint.

Prior to that discovery, the $20 Liberty gold coins from that mint were so rare that only eight were known to exist in mint condition. Once the finders won the right to sell the coins at public auction, the treasure brought a whopping prize of $5.3 million.

By James Donahue

When the steamship Brother Jonathan set its course on July 28, 1865, from the gold fields of San Francisco for Portland, Oregon, it was carrying a fortune in gold coins. But it was also a damaged ship that had been improperly patched, and was foolishly overloaded with cargo and passengers before it was sent out to sea in a gale.

Thus the Brother Jonathan was destined to wreck. The gale that developed the following day stressed the 13-year-old hull and an uncharted reef off the coast of Crescent City, California, doomed the ship and all but 19 of her 244 passengers and crew members to a watery grave.

The discovery of the remains of the steamer by a dive research team in 1993 sparked a long legal battle and the State of California over ownership of the rare minted gold coins that eventually brought $5.3 million in auction. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court before it was unanimously decided in favor of the finders.

The Brother Jonathan was built at the shipyards of Perrine, Patterson and Stack at Williamsburg, N.Y., in 1850 for New York businessman Edward Mills. He placed the ship the following year on a regular run, carrying passengers in the great gold rush from New York to Chagres, the old name for Colon, Panama, on their way to San Francisco.

The Panama Canal did not exist yet so people who took that route had to travel by foot or mule through the jungle to Panama, where they took another ship to Panama. It was one of three routes to go in those days. The options were to hop a clipper ship for a long trip around Cape Horn, South America, or travel my wagon across country.

The Brother Jonathan measured 220 feet in length. It had a superstructure of upper and lower decks and boasted two 70-foot salons decorated with gilt and enamel. She was driven by two massive side-mounted paddle wheels driven by a vertical beam engine. She also was rigged as a modified two-masted barkentine.

Artist’s drawings show the ship with a single stack forward of the sidewheels. It was said that the bow was ornamented with trail boards and a billet head. The hull was black with blue wale and buff deckhouses. The wheel boxes were done in black and red, with gilt eagles painted on the side panels. A gilded eagle also appeared on the stern.

Shipbuilders of that day took pride in their craft, and turned out fine workmanship. The New York Herald on Nov. 27, 1850, on reporting the launching of the ship, described the construction of the hull as follows:

“Her floors are solid, 14 inches in depth, bolted together with one and three-quarter inch iron; five keelsons and head pieces cadged and bolted to the solid floor. The frame, at the turn of the bilge, is peculiar for its great strength, being additionally secured by strong iron diagonal braces, forming a perfect network from stem to stern; over which is laid yellow pine blanking from five to eight inches thick and all square fastened. The decks are of the most substantial description, being thoroughly secured with lodging and hanging knees. The outside if planked with white oak, and well tree nailed and copper fastened.”

That was how the Brother Jonathan looked when it was new. The vessel went through two major refittings during its years on the high seas. After a long trip from New York to San Francisco around the horn, the vessel was sold to new owners who put it on a regular run from San Francisco to Portland.

She was still on that run in July, 1865 when it was wrecked on an uncharted reef, now known as Jonathan Rock. The steamer had a new master, identified as Captain DeWolf, who took command in June of that year.

The Brother Jonathan was involved in a collision with the barkentine Jane Falkenberg while on the Columbia River. Captain DeWolf brought the ship back to San Francisco where he expected it to be put in dry dock for proper repair of the damaged hull. But the owners, anxious to avoid a lengthy delay in the middle of a busy and profitable shipping season, ordered makeshift repairs at the dock.

Next the company’s agent stacked the holds and decks with so much cargo that Captain DeWolf objected. He complained that it was too dangerous to sail the steamer in that condition. The agent warned that if DeWolf refused to take the vessel out, he would find another captain who would.

The cargo for that fateful trip included crates of $20 gold pieces, an estimated $200,000 to pay the troops at Fort Vancouver, Walla Walla, and other posts in the Northwest. It was believed that gold coins also were earmarked for an annual treaty payment for the Indian tribes and that other gold was destined for private transfers.

The ship was so heavily laden that its hull was embedded in the mud at the dock. The departure was delayed until high tide, when tugs helped pull it free and out to sea. The steamer was riding low in the water as it sluggishly pushed its way through the Golden Gate and turned north into a strong headwind and heavy seas. On board were 190 passengers and 54 crew members.

The Brother Jonathan called briefly at Crescent City to offload cargo at about 2 a.m. the next day. By mid-morning it was back to sea, battling a developing gale in an effort to clear St. George’s Reef. Captain DeWolf soon decided to turn the ship around and run back to Crescent City to wait out the storm.

When about four miles from the coast, the steamer struck the rock. The force of the moving ship, the wind and the seas first penetrated the oak hull, then tore at the bottom of the ship. DeWolf ordered everyone aft to “try and save themselves.”

Attempts to launch the ship’s lifeboats ended in disaster. The first lowered boat capsized immediately. The second boat, full of women, was being lowered astern of the paddle wheels when a giant wave smashed the boat into the side of the ship. The crew managed to get the passengers back on the Jonathan before the boat was smashed to pieces under their feet.

The only boat to get away safely was a wooden surfboat, commanded by Third Mate Patterson. With him were 10 other crew members, five women and three children. They just got away safely when the Jonathan sank by the bow, carrying everyone else down with it. They were the only survivors.

The storm prevented any rescue attempts from land that day. Bodies and wreckage floated ashore for several weeks after that.

For years after that, the story was told about the wreck of the Brother Jonathan and its lost gold treasure chests. Coin collectors were especially interested in the wreck because it was said to have carried rare Liberty gold coins minted in 1865 at the San Francisco Mint.

Prior to that discovery, the $20 Liberty gold coins from that mint were so rare that only eight were known to exist in mint condition. Once the finders won the right to sell the coins at public auction, the treasure brought a whopping prize of $5.3 million.