Head Transplant – What is Next in Medicine?

By James Donahue

September 26, 2016

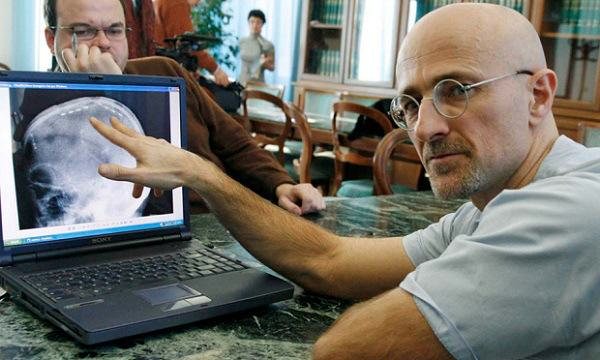

The news that an Italian neurosurgeon, Dr. Sergio Canavero, plans to carry out the complete transplantation of a human head sounds almost too incredible to believe. But I remember that I responded in much the same way when Dr. Christiaan Barnard of South Africa performed the world’s first human-to-human heart transplant.

Barnard’s operation was successful in that he managed to keep the heart’s recipient, 54-year-old Louis Washkansky, alive for 18 days after receiving the heart.

Since Barnard’s dynamic breakthrough in organ transplantation, surgeons all over the world have been successfully transplanting body parts . . . everything from hearts and kidneys to eyes and lungs. But the concept of transplanting the complete head of one person to the body of another seems to be beyond the pale if not mortiferous.

Dr. Canavero apparently has a volunteer for such an extreme surgery. He is Valery Spiridonov, a 30-year-old computer scientist in Vladimir, Russia, who was born with a rare genetic muscle wasting condition known as Werdnig-Hoffman disease. He has no control of his body functions including the motor neurons in the spinal cord and the part of his brain that is connected to the spinal cord.

In other words, Spiridonov exists only in his head. He is not expected to live much longer and is volunteering for this radical head transplant in the hope that he might experience what it is like to live with a whole body before he dies.

Now all Canavero and Spirdonov need is a complete and undamaged but dying body that needs a head.

Canavero will not be alone in the operating room when this amazing transplant is attempted. He expects to be accompanied by about 100 surgeons. The procedure will take an estimated 36 hours to complete.

Canavero and other surgeons have been experimenting with head transplants on small animals, including dogs and monkeys, and having some degree of success. In 1970 a team of scientists led by Dr. Robert White, a professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, successfully transplanted the head of a monkey onto the body of another monkey. The animal was able to smell, taste, hear and see and was kept chemically alive for a while.

There lies deep within this story a plot that might rival the very best works of such terror writers as Edgar Allen Poe and Stephen King.

During the procedure on Spirdonov, which may not occur for another year or longer, surgeons will carefully remove the heads of the two bodies and carefully fuse the spinal cords while suturing the muscles and blood supply. Special chemicals called polyethylene glycol or chitosan may be used to keep both the head and body functioning during the surgery.

The patient will be kept in a coma for about a month, Canavero explains. During this time the spinal cord will be given electrical stimulation through implanted electrodes to keep nerve connections alive.

While the very thought of having our heads removed and then transplanted on another body seems somewhat grotesque, there is something strangely romantic about the idea as well. Imagine having our heads moved from body to body after the old body’s age and wear out. We might someday be able to live for hundreds of years as long as the surgeons don’t screw up along the way.

We would also have to have the finances to pay 100 surgeons to perform in the operating rooms non-stop for 36 hours. We doubt that Blue Cross or Medicare has a policy to cover that sort of thing.

By James Donahue

September 26, 2016

The news that an Italian neurosurgeon, Dr. Sergio Canavero, plans to carry out the complete transplantation of a human head sounds almost too incredible to believe. But I remember that I responded in much the same way when Dr. Christiaan Barnard of South Africa performed the world’s first human-to-human heart transplant.

Barnard’s operation was successful in that he managed to keep the heart’s recipient, 54-year-old Louis Washkansky, alive for 18 days after receiving the heart.

Since Barnard’s dynamic breakthrough in organ transplantation, surgeons all over the world have been successfully transplanting body parts . . . everything from hearts and kidneys to eyes and lungs. But the concept of transplanting the complete head of one person to the body of another seems to be beyond the pale if not mortiferous.

Dr. Canavero apparently has a volunteer for such an extreme surgery. He is Valery Spiridonov, a 30-year-old computer scientist in Vladimir, Russia, who was born with a rare genetic muscle wasting condition known as Werdnig-Hoffman disease. He has no control of his body functions including the motor neurons in the spinal cord and the part of his brain that is connected to the spinal cord.

In other words, Spiridonov exists only in his head. He is not expected to live much longer and is volunteering for this radical head transplant in the hope that he might experience what it is like to live with a whole body before he dies.

Now all Canavero and Spirdonov need is a complete and undamaged but dying body that needs a head.

Canavero will not be alone in the operating room when this amazing transplant is attempted. He expects to be accompanied by about 100 surgeons. The procedure will take an estimated 36 hours to complete.

Canavero and other surgeons have been experimenting with head transplants on small animals, including dogs and monkeys, and having some degree of success. In 1970 a team of scientists led by Dr. Robert White, a professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, successfully transplanted the head of a monkey onto the body of another monkey. The animal was able to smell, taste, hear and see and was kept chemically alive for a while.

There lies deep within this story a plot that might rival the very best works of such terror writers as Edgar Allen Poe and Stephen King.

During the procedure on Spirdonov, which may not occur for another year or longer, surgeons will carefully remove the heads of the two bodies and carefully fuse the spinal cords while suturing the muscles and blood supply. Special chemicals called polyethylene glycol or chitosan may be used to keep both the head and body functioning during the surgery.

The patient will be kept in a coma for about a month, Canavero explains. During this time the spinal cord will be given electrical stimulation through implanted electrodes to keep nerve connections alive.

While the very thought of having our heads removed and then transplanted on another body seems somewhat grotesque, there is something strangely romantic about the idea as well. Imagine having our heads moved from body to body after the old body’s age and wear out. We might someday be able to live for hundreds of years as long as the surgeons don’t screw up along the way.

We would also have to have the finances to pay 100 surgeons to perform in the operating rooms non-stop for 36 hours. We doubt that Blue Cross or Medicare has a policy to cover that sort of thing.