The Floating Gambling Ship

By James Donahue

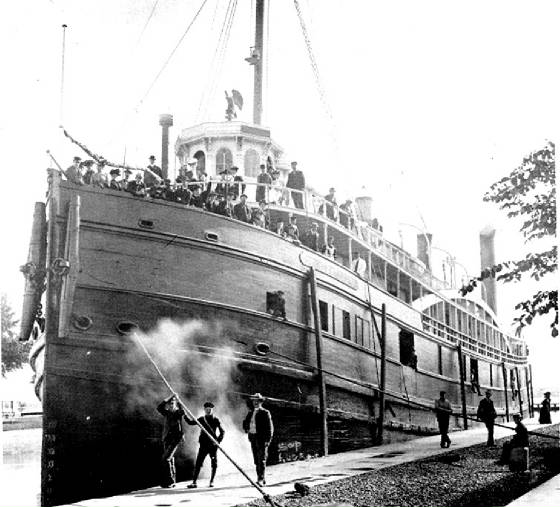

The elegant Great Lakes steamship City of Traverse had fallen on hard times. Since its launch in 1871, the vessel faithfully carried passengers and freight between Chicago and Traverse City. In most of its years, the vessel had only two masters, Capt. George Baldwin and later his son, Capt. Thomas Baldwin.

But now it was 1905, and the oak-hulled ship had outlived her usefulness. The new owner, Captain Stephen Jones, had a plan to turn it into a floating gambling casino with the help of the latest technological gadget, the wireless telegraph.

Betting on horse races was prohibited in Chicago, where racing was a popular sport. But Jones and his business partner, a man identified as "Bud" White, reasoned that the City of Traverse could ferry customers to a point beyond a three-mile limit of the Illinois shoreline where they could bet on the races via the wireless, and the state law did not apply.

Gambling, considered an evil and addictive vice, was prohibited in most states, but in 1905 there was no federal law against it. The laws of the day gave states jurisdiction on the water for three miles from the coast. After that, the water was controlled by national or international law, depending on the lake.

A writer for the Duluth Evening Herald, in reporting the fate of the City of Traverse, lamented its demise. He said the grand old ship was being "degraded to a pool room." The story said the main deck was being fitted out as a bar and restaurant, and the saloon deck opened as a large gambling room stretching almost the length of the 214-foot vessel.

When the ship was ready to take its first load of gamblers out for a day on Lake Michigan, local authorities were scrambling to find a way to stop it.

The Illinois Central Railway, which owned the dock where the steamer was moored, attempted to force the vessel to move, but the harbormaster, who had jurisdiction over the docks where the vessels were moored, intervened. When the City of Traverse sailed, four Chicago police officers were on board, making sure no laws were violated within the three-mile limit.

For a week or two, the floating gambling casino was a big hit. People packed the decks and enjoyed themselves, while prudent authorities on shore racked their brains trying to find a way to stop it.

On Independence Day, the police located the land-based telegraph office where the information on the races was being transmitted. The office was raided and all of the telegraph equipment seized. The office manager and his two assistants were arrested and hauled off to jail.

Jones and White had anticipated such a raid, and there was a second secret telegraph office in place for just such an emergency. The casino sailed on, and the bets continued to be placed without interruption.

After that, the police began arresting patrons of the gambling boat, charging them with soliciting. The gamblers began disguising themselves as fishermen, and said they were only going to the docks to catch some fish. The steamer began anchoring off shore, and transporting patrons from the docks via small motor boats named the Florence and the Chester.

Finally, during the first week of August, a police line was established at the dock. Lt. Walter Jenkins and a squad of about 25 other police officers formed a line that stood firm, preventing anyone from entering the dock.

A force of more than 1,000 police officers were on stand-by in case of trouble. By about 1 p.m. that day, an estimated 400 citizens stood facing the police blockade. Many were area residents who heard about the confrontation and just came to watch.

The blockade worked and the gambling boat did not make a cruise that day. A day or two later, the police raided the steamer and arrested the passengers on gambling charges.

The matter went to court and a local judge ruled that the police could not charge people with gambling if they did not see it and if they could not prove that gambling was going on. It appeared as if the City of Traverse could not be stopped.

Next the Illinois State Attorney General, identified as Mr. Lindley, got involved. He said he found a state law against "conspiring to gamble," which was punishable by a prison term. "If the City of Traverse continues to sail in Illinois waters for gambling purposes we'll soon swamp the entire crew," he announced.

Captain Jones continued dodging the police and taking passengers for weeks after this, always keeping one step ahead of the police. Finally, late in the season, the authorities found a technical flaw and managed to get the ship's operating license revoked.

Captain Jones was arrested and fined $500 for violation of some obscure law, and the floating poolroom was out of business.

The City of Traverse was sold in 1907 to Graham & Morton Transportation Co. of Chicago and withdrawn from passenger service after one additional season. It was finally converted to serve as a floating dry dock at St. Joseph, Michigan.

By James Donahue

The elegant Great Lakes steamship City of Traverse had fallen on hard times. Since its launch in 1871, the vessel faithfully carried passengers and freight between Chicago and Traverse City. In most of its years, the vessel had only two masters, Capt. George Baldwin and later his son, Capt. Thomas Baldwin.

But now it was 1905, and the oak-hulled ship had outlived her usefulness. The new owner, Captain Stephen Jones, had a plan to turn it into a floating gambling casino with the help of the latest technological gadget, the wireless telegraph.

Betting on horse races was prohibited in Chicago, where racing was a popular sport. But Jones and his business partner, a man identified as "Bud" White, reasoned that the City of Traverse could ferry customers to a point beyond a three-mile limit of the Illinois shoreline where they could bet on the races via the wireless, and the state law did not apply.

Gambling, considered an evil and addictive vice, was prohibited in most states, but in 1905 there was no federal law against it. The laws of the day gave states jurisdiction on the water for three miles from the coast. After that, the water was controlled by national or international law, depending on the lake.

A writer for the Duluth Evening Herald, in reporting the fate of the City of Traverse, lamented its demise. He said the grand old ship was being "degraded to a pool room." The story said the main deck was being fitted out as a bar and restaurant, and the saloon deck opened as a large gambling room stretching almost the length of the 214-foot vessel.

When the ship was ready to take its first load of gamblers out for a day on Lake Michigan, local authorities were scrambling to find a way to stop it.

The Illinois Central Railway, which owned the dock where the steamer was moored, attempted to force the vessel to move, but the harbormaster, who had jurisdiction over the docks where the vessels were moored, intervened. When the City of Traverse sailed, four Chicago police officers were on board, making sure no laws were violated within the three-mile limit.

For a week or two, the floating gambling casino was a big hit. People packed the decks and enjoyed themselves, while prudent authorities on shore racked their brains trying to find a way to stop it.

On Independence Day, the police located the land-based telegraph office where the information on the races was being transmitted. The office was raided and all of the telegraph equipment seized. The office manager and his two assistants were arrested and hauled off to jail.

Jones and White had anticipated such a raid, and there was a second secret telegraph office in place for just such an emergency. The casino sailed on, and the bets continued to be placed without interruption.

After that, the police began arresting patrons of the gambling boat, charging them with soliciting. The gamblers began disguising themselves as fishermen, and said they were only going to the docks to catch some fish. The steamer began anchoring off shore, and transporting patrons from the docks via small motor boats named the Florence and the Chester.

Finally, during the first week of August, a police line was established at the dock. Lt. Walter Jenkins and a squad of about 25 other police officers formed a line that stood firm, preventing anyone from entering the dock.

A force of more than 1,000 police officers were on stand-by in case of trouble. By about 1 p.m. that day, an estimated 400 citizens stood facing the police blockade. Many were area residents who heard about the confrontation and just came to watch.

The blockade worked and the gambling boat did not make a cruise that day. A day or two later, the police raided the steamer and arrested the passengers on gambling charges.

The matter went to court and a local judge ruled that the police could not charge people with gambling if they did not see it and if they could not prove that gambling was going on. It appeared as if the City of Traverse could not be stopped.

Next the Illinois State Attorney General, identified as Mr. Lindley, got involved. He said he found a state law against "conspiring to gamble," which was punishable by a prison term. "If the City of Traverse continues to sail in Illinois waters for gambling purposes we'll soon swamp the entire crew," he announced.

Captain Jones continued dodging the police and taking passengers for weeks after this, always keeping one step ahead of the police. Finally, late in the season, the authorities found a technical flaw and managed to get the ship's operating license revoked.

Captain Jones was arrested and fined $500 for violation of some obscure law, and the floating poolroom was out of business.

The City of Traverse was sold in 1907 to Graham & Morton Transportation Co. of Chicago and withdrawn from passenger service after one additional season. It was finally converted to serve as a floating dry dock at St. Joseph, Michigan.