Saga of the Olive Jeannette

By James Donahue

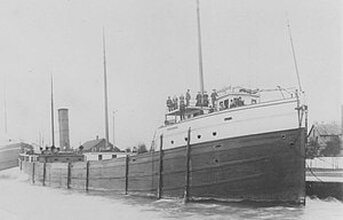

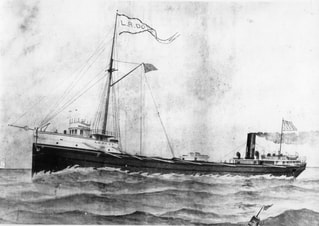

When the steamer Iosco and her tow, the schooner Olive Jeannette, foundered with all hands during a Lake Superior gale in 1905, lake men wondered if the schooner was cursed. The Jeannette was involved in an almost identical disaster, that time with the Iosco’s sister vessel, the L. R. Doty, during a storm on Lake Michigan in 1898.

The Doty sank with all hands, but the Jeannette hoisted sail and survived to sail again. Seventeen sailors perished when the Doty, owned by the Cuyahoga Transit Company of Chicago, disappeared in the gale of October 25. Capt. David B. Cadotte, forty-eight-year-old master of the Jeannette, was credited with bringing his schooner through the storm against almost impossible odds. That story is among the best in the annals of lake lore.

The Doty was steaming north from Chicago to Midland, Ontario, with a load of corn, and had the Jeannette in tow, when the two boats got caught in a northerly gale. Cadotte said the Jeannette broke her towline about 5:00 PM a few miles northeast of Milwaukee. The Doty didn’t stop, and was last seen steaming north into the teeth of the gale. He said everything appeared to be all right aboard the steamer at that time. Cadotte ordered canvass spread on the Jeannette and he started running the schooner before the wind toward Racine. It was a long and dangerous trip, and waves continually rolled over the stern of the schooner, drenching the sailors working on its deck, but she was making progress. Then at about 11:00 PM, when the Racine light was in sight and safety only about an hour away, the vessel’s steering fouled and the schooner fell off into the trough of the sea. The monster waves began rolling over the side and they swept the deck clean. Before long, Cadotte said, the waves carried away the steam pumps, deck housing and everything that wasn’t fastened down.

While all this was going on, the crew struggled against the storm to toggle up the steering chains so that the Jeannette could make another try for safe harbor. Before they succeeded the gale blew the schooner south past Racine. When the rudder was again under control, Cadotte chose to turn southwest and make a run toward Chicago. But it wasn’t long before the constant buffeting by wind and sea against the stern wrecked the steering system again. This time it could not be repaired. Thus the Jeannette was again at the mercy of the storm.

She drifted for the rest of the night, taking a violent beating. The ten men aboard her decks spent an ugly night at sea, clinging to the ship but finding no place to get dry, no shelter from the gale. Surprisingly, the hatches remained in place and that saved the boat. A steamer found the Jeannette still adrift a few miles off Chicago the next day and towed it into port.

The Doty never made port. She was declared lost on October 27 when the tug Prodigy found wreckage from a steamer about twenty-five miles off Kenosha. The debris included pieces of deck, a pole mast, cabin doors, stanchions and part of the steering pole from the bow. The exact location of the Doty was not known. It was theorized that the steamer developed engine trouble in the storm and drifted off in the trough of the sea. The Doty had a full cargo and because it had a low freeboard, probably took a severe pounding from the storm after it began striking her broadside. If the hatch covers failed, the boat would have quickly filled and foundered. Seventeen sailors died on the Doty. They included Capt. Christopher Smith of Port Huron, chief engineer Thomas Abernethy of Port Huron, assistant engineer Charles Odette of Cleveland, first mate Harry Sharpe of Detroit, steward L. Goss of Bay City, second mate W. J. Hosie of Detroit, oiler Wallace Watkins, cook W. J. Scott, watchman Charles Barrie, wheelmen Pete G. Peterson and Albert Nelson, firemen Joseph Fitzsimmons and J. Howe, and deck hands F. Parmuth, C. Curtis, William Ebert, Pat Ryan, Frank Burke and T. Trainer.

The story continues four years later. The Jeanette was lost on September 3, 1905, when she foundered with the steamer Iosco off Huron Islands, on Lake Superior. They said the Iosco was a carbon copy of the Doty. When the two boats were together experienced sailors had to look twice to tell one from the other. Their sinkings, right down to the towline to the Jeannette, were mysteriously similar.

Both the Iosco and the Jeannette were laden with iron ore when they left Duluth bound for Buffalo. The storm hit them in the middle of Lake Superior. There were no survivors, so nobody knows what happened. The Iosco apparently went down first because a lighthouse keeper at Huron Island said he didn’t see a steamer when he watched the Olive Jeanette founder about four miles north of the island about 4:00 PM. He said the big four-mast schooner had jib and foresail set and was nearly waterlogged before it sank. The tug D. L. Hebard discovered wreckage, including life preservers marked Iosco, near the island the next day, so it is believed both boats foundered in the same area.

Twenty-seven sailors died on the two boats. The Iosco carried a crew of nineteen; while the Jeannette had eight men aboard. The Iosco’s crew included Capt. Nelson Gonyaw of Bay City, chief engineer Frank M. Gordon of Cleveland, mate F. H. Griffin, second engineer George Shaw, oiler Martin W. Stanton, steward W. B. Barnes, assistant steward Mr. Barnes, watchmen Arthur Roberts and Robert Ray, wheelmen Matthew Cummings and John Brooks, firemen Charles Graff, August Frank, Andrew Murphy and A. McDonald, and deck hands J. Smith, M. J. Martin, Victor Glamlin and Alfred Lewis. The lost crew on the Jeannette included Captain McGreery of Buffalo, mate J. Waller, engineer J. M. Dunn, steward William Johnson and sailors G. Bohlin, J. Ellison, James Gibarson and Charles Showman.

The boats were owned by W. A. Hawgood and Company of Cleveland.

By James Donahue

When the steamer Iosco and her tow, the schooner Olive Jeannette, foundered with all hands during a Lake Superior gale in 1905, lake men wondered if the schooner was cursed. The Jeannette was involved in an almost identical disaster, that time with the Iosco’s sister vessel, the L. R. Doty, during a storm on Lake Michigan in 1898.

The Doty sank with all hands, but the Jeannette hoisted sail and survived to sail again. Seventeen sailors perished when the Doty, owned by the Cuyahoga Transit Company of Chicago, disappeared in the gale of October 25. Capt. David B. Cadotte, forty-eight-year-old master of the Jeannette, was credited with bringing his schooner through the storm against almost impossible odds. That story is among the best in the annals of lake lore.

The Doty was steaming north from Chicago to Midland, Ontario, with a load of corn, and had the Jeannette in tow, when the two boats got caught in a northerly gale. Cadotte said the Jeannette broke her towline about 5:00 PM a few miles northeast of Milwaukee. The Doty didn’t stop, and was last seen steaming north into the teeth of the gale. He said everything appeared to be all right aboard the steamer at that time. Cadotte ordered canvass spread on the Jeannette and he started running the schooner before the wind toward Racine. It was a long and dangerous trip, and waves continually rolled over the stern of the schooner, drenching the sailors working on its deck, but she was making progress. Then at about 11:00 PM, when the Racine light was in sight and safety only about an hour away, the vessel’s steering fouled and the schooner fell off into the trough of the sea. The monster waves began rolling over the side and they swept the deck clean. Before long, Cadotte said, the waves carried away the steam pumps, deck housing and everything that wasn’t fastened down.

While all this was going on, the crew struggled against the storm to toggle up the steering chains so that the Jeannette could make another try for safe harbor. Before they succeeded the gale blew the schooner south past Racine. When the rudder was again under control, Cadotte chose to turn southwest and make a run toward Chicago. But it wasn’t long before the constant buffeting by wind and sea against the stern wrecked the steering system again. This time it could not be repaired. Thus the Jeannette was again at the mercy of the storm.

She drifted for the rest of the night, taking a violent beating. The ten men aboard her decks spent an ugly night at sea, clinging to the ship but finding no place to get dry, no shelter from the gale. Surprisingly, the hatches remained in place and that saved the boat. A steamer found the Jeannette still adrift a few miles off Chicago the next day and towed it into port.

The Doty never made port. She was declared lost on October 27 when the tug Prodigy found wreckage from a steamer about twenty-five miles off Kenosha. The debris included pieces of deck, a pole mast, cabin doors, stanchions and part of the steering pole from the bow. The exact location of the Doty was not known. It was theorized that the steamer developed engine trouble in the storm and drifted off in the trough of the sea. The Doty had a full cargo and because it had a low freeboard, probably took a severe pounding from the storm after it began striking her broadside. If the hatch covers failed, the boat would have quickly filled and foundered. Seventeen sailors died on the Doty. They included Capt. Christopher Smith of Port Huron, chief engineer Thomas Abernethy of Port Huron, assistant engineer Charles Odette of Cleveland, first mate Harry Sharpe of Detroit, steward L. Goss of Bay City, second mate W. J. Hosie of Detroit, oiler Wallace Watkins, cook W. J. Scott, watchman Charles Barrie, wheelmen Pete G. Peterson and Albert Nelson, firemen Joseph Fitzsimmons and J. Howe, and deck hands F. Parmuth, C. Curtis, William Ebert, Pat Ryan, Frank Burke and T. Trainer.

The story continues four years later. The Jeanette was lost on September 3, 1905, when she foundered with the steamer Iosco off Huron Islands, on Lake Superior. They said the Iosco was a carbon copy of the Doty. When the two boats were together experienced sailors had to look twice to tell one from the other. Their sinkings, right down to the towline to the Jeannette, were mysteriously similar.

Both the Iosco and the Jeannette were laden with iron ore when they left Duluth bound for Buffalo. The storm hit them in the middle of Lake Superior. There were no survivors, so nobody knows what happened. The Iosco apparently went down first because a lighthouse keeper at Huron Island said he didn’t see a steamer when he watched the Olive Jeanette founder about four miles north of the island about 4:00 PM. He said the big four-mast schooner had jib and foresail set and was nearly waterlogged before it sank. The tug D. L. Hebard discovered wreckage, including life preservers marked Iosco, near the island the next day, so it is believed both boats foundered in the same area.

Twenty-seven sailors died on the two boats. The Iosco carried a crew of nineteen; while the Jeannette had eight men aboard. The Iosco’s crew included Capt. Nelson Gonyaw of Bay City, chief engineer Frank M. Gordon of Cleveland, mate F. H. Griffin, second engineer George Shaw, oiler Martin W. Stanton, steward W. B. Barnes, assistant steward Mr. Barnes, watchmen Arthur Roberts and Robert Ray, wheelmen Matthew Cummings and John Brooks, firemen Charles Graff, August Frank, Andrew Murphy and A. McDonald, and deck hands J. Smith, M. J. Martin, Victor Glamlin and Alfred Lewis. The lost crew on the Jeannette included Captain McGreery of Buffalo, mate J. Waller, engineer J. M. Dunn, steward William Johnson and sailors G. Bohlin, J. Ellison, James Gibarson and Charles Showman.

The boats were owned by W. A. Hawgood and Company of Cleveland.