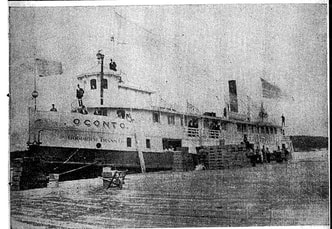

Wreck of the Oconto

By James Donahue

First mate Charles Rearden of Port Huron told a story of real terror at sea after his ship, the steamer Oconto, got caught in a severe northeastern gale and blinding snowstorm the night of December 4, 1885.

The one hundred forth-three-foot vessel, with Capt. G. W. McGregor of Lexington, Michigan at the helm, left Oscoda at 4:00 PM and was steaming north along the Michigan coast bound for Alpena. On board were forty-seven passengers and crew members, a hundred tons of freight, plus an unknown number of cows and horses. The upper decks were packed with cutters and sleighs, plus crates filled with about a hundred chickens and turkeys.

The overloaded and outdated wooden hulled steamer was not prepared for the winter blast that awaited her on Lake Huron. What began as a three-hour, seventy-mile trip up the lake shore turned into a two-day period of extreme hardship.

Captain McGregor gave up plans to continue on to Alpena to the north after the storm blew up and massive seas began sweeping the decks. Instead he turned the boat and aimed her southwest for Tawas Bay.

A heavy wet snow began falling and before long the Oconto was running blind, Rearden said. The vessel was rolling violently and all was chaos below deck. “After supper the horses and cattle broke loose The cattle were thrown in all directions. A gangway was broken in and stanchions were broken. I saw that one cow had a broken leg,” he said.

While the men were struggling with the livestock, Rearden said he heard William Brown, the ship’s cook, yelling for help. He later found Brown dead in his bed, apparently from fright, and the galley stove was glowing red hot. Fearing a fire aboard ship, Rearden dowsed the fire in the stove. As the seas swept the decks, he said the chickens, turkeys and sleighs were swept overboard.

Up in the pilothouse, Captain McGregor was using all of his skill to try to bring his command safely through the gale. As darkness closed in, McGregor began getting glimpses of a light and steered for it.

What he saw turned out to be the lighthouse on Charity Island, in the middle of Saginaw Bay. As he drew near, McGregor guessed where he was and ordered a new course, but he was too late. Within moments the Oconto hit the rocks, Rearden said. “We struck a couple of times and then checked down. After that we put on all steam and let her go on the beach as far as she would go,” he said.

Everybody remained aboard the wreck for two days before the storm abated enough for a lifeboat to reach the island safely. They spent another night at the lighthouse until a ship took them back to the mainland.

The Oconto was salvaged the following spring. After going through extensive repair, the ship made one final voyage down the lakes to New York. On July 6, 1886, it struck a shoal on the St. Lawrence River, put a hole in her bottom, and sank in one hundred ninety-two feet of water.

By James Donahue

First mate Charles Rearden of Port Huron told a story of real terror at sea after his ship, the steamer Oconto, got caught in a severe northeastern gale and blinding snowstorm the night of December 4, 1885.

The one hundred forth-three-foot vessel, with Capt. G. W. McGregor of Lexington, Michigan at the helm, left Oscoda at 4:00 PM and was steaming north along the Michigan coast bound for Alpena. On board were forty-seven passengers and crew members, a hundred tons of freight, plus an unknown number of cows and horses. The upper decks were packed with cutters and sleighs, plus crates filled with about a hundred chickens and turkeys.

The overloaded and outdated wooden hulled steamer was not prepared for the winter blast that awaited her on Lake Huron. What began as a three-hour, seventy-mile trip up the lake shore turned into a two-day period of extreme hardship.

Captain McGregor gave up plans to continue on to Alpena to the north after the storm blew up and massive seas began sweeping the decks. Instead he turned the boat and aimed her southwest for Tawas Bay.

A heavy wet snow began falling and before long the Oconto was running blind, Rearden said. The vessel was rolling violently and all was chaos below deck. “After supper the horses and cattle broke loose The cattle were thrown in all directions. A gangway was broken in and stanchions were broken. I saw that one cow had a broken leg,” he said.

While the men were struggling with the livestock, Rearden said he heard William Brown, the ship’s cook, yelling for help. He later found Brown dead in his bed, apparently from fright, and the galley stove was glowing red hot. Fearing a fire aboard ship, Rearden dowsed the fire in the stove. As the seas swept the decks, he said the chickens, turkeys and sleighs were swept overboard.

Up in the pilothouse, Captain McGregor was using all of his skill to try to bring his command safely through the gale. As darkness closed in, McGregor began getting glimpses of a light and steered for it.

What he saw turned out to be the lighthouse on Charity Island, in the middle of Saginaw Bay. As he drew near, McGregor guessed where he was and ordered a new course, but he was too late. Within moments the Oconto hit the rocks, Rearden said. “We struck a couple of times and then checked down. After that we put on all steam and let her go on the beach as far as she would go,” he said.

Everybody remained aboard the wreck for two days before the storm abated enough for a lifeboat to reach the island safely. They spent another night at the lighthouse until a ship took them back to the mainland.

The Oconto was salvaged the following spring. After going through extensive repair, the ship made one final voyage down the lakes to New York. On July 6, 1886, it struck a shoal on the St. Lawrence River, put a hole in her bottom, and sank in one hundred ninety-two feet of water.