Phrenology – Understanding The Human Brain In 1800.

By James Donahue

I recall a college sociology class where we examined early attempts to determine criminal behavior by looking at the shape of the human head. We laughed at the thought that men of learning in the Nineteenth Century might dream up such an idea.

Viennese physician Franz Joseph Gall, who lived from 1758 to 1828, carried this concept one step farther by creating the science of Phrenology. He called it the true science of the mind. It was a peculiar mapping of the human head that determined personality by the shape of the skull.

While these ideas, which excited the medical community only 200 years ago, seem silly to us now, we must understand that the human brain was a mystery to researchers until the invention of contemporary tools like X-ray, ultra-sound, EEG and CT scanning machines that not only produce graphic images of every part of the human body, but allow researchers to study electrical impulses of the brain.

Gall's theory was based on the shape of the skull, which he believed housed parts of the brain that controlled a person's personality traits, propensities and even intelligence. The Edinburgh Phrenological Society, established by George and Andrews Combe in Edinburgh, England, in 1820, became an influence in Nineteenth Century psychiatry.

While it was always a pseudoscience, in that phrenology had no technological scientific proofs to support Gall's ideas, the concept gained popularity throughout the English speaking world. That may have been because Gall was correct in his belief that certain parts of the brain are linked to specific activities of the mind and body. This has been proven by contemporary brain scans that show electrical impulses in the brain lighting up when the patient is involved in activities like enjoying great music, expressing anger or doing creative things.

Gall's ideas were actually a step closer to modern concepts of medicine and psychology from the dramatic changes in thinking promoted by Greek physician Hippocrates. It was Hippocrates who first identified the brain as the major controlling center for the body. Before that, it was believed that the primary control of bodily functions came from the heart.

Strangely enough, contemporary researchers have determined that both ideas may have been somewhat correct. It has been discovered that the heart contains much of the same tissue found in the human brain and that it may, indeed, be more closely related to human emotion than we used to think. There is a thought that the heart is an extension of the brain.

But we digress.

It was Swiss pastor Johann Kaspar Lavater who introduced the idea that physiognomy revealed specific character traits of people instead of general types. His ideas, outlined in his book Physiognomische Fragmente, may have helped in the eventual "mapping" of the brain by followers of Gall.

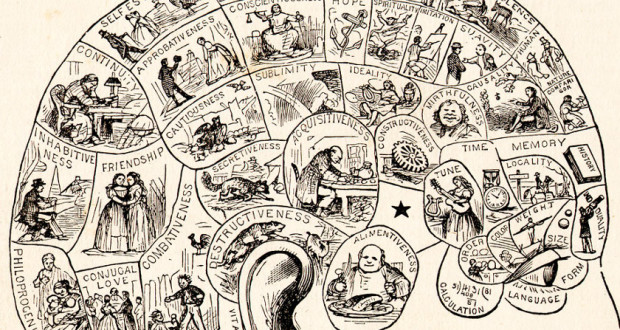

It is interesting to study the various published images of the human head, showing areas of the brain believed linked to specific emotions and activities of the body. Few of them show a general consensus of opinion among practitioners.

Nevertheless, during the heyday of physiognomy employers would go so far as to demand a character reference from a local phrenologist to make sure that the potential employee was honest and right for the job. The concept also was used to determine intelligence and criminality. Young people turned to physiognomy in their search for a perfect mate.

We still do all of this today except the assessments are being done by psychics, clairvoyants, astrologers and medical labs searching for narcotics in the blood.

We humans are a peculiar bunch. The more things change the more they stay the same.

By James Donahue

I recall a college sociology class where we examined early attempts to determine criminal behavior by looking at the shape of the human head. We laughed at the thought that men of learning in the Nineteenth Century might dream up such an idea.

Viennese physician Franz Joseph Gall, who lived from 1758 to 1828, carried this concept one step farther by creating the science of Phrenology. He called it the true science of the mind. It was a peculiar mapping of the human head that determined personality by the shape of the skull.

While these ideas, which excited the medical community only 200 years ago, seem silly to us now, we must understand that the human brain was a mystery to researchers until the invention of contemporary tools like X-ray, ultra-sound, EEG and CT scanning machines that not only produce graphic images of every part of the human body, but allow researchers to study electrical impulses of the brain.

Gall's theory was based on the shape of the skull, which he believed housed parts of the brain that controlled a person's personality traits, propensities and even intelligence. The Edinburgh Phrenological Society, established by George and Andrews Combe in Edinburgh, England, in 1820, became an influence in Nineteenth Century psychiatry.

While it was always a pseudoscience, in that phrenology had no technological scientific proofs to support Gall's ideas, the concept gained popularity throughout the English speaking world. That may have been because Gall was correct in his belief that certain parts of the brain are linked to specific activities of the mind and body. This has been proven by contemporary brain scans that show electrical impulses in the brain lighting up when the patient is involved in activities like enjoying great music, expressing anger or doing creative things.

Gall's ideas were actually a step closer to modern concepts of medicine and psychology from the dramatic changes in thinking promoted by Greek physician Hippocrates. It was Hippocrates who first identified the brain as the major controlling center for the body. Before that, it was believed that the primary control of bodily functions came from the heart.

Strangely enough, contemporary researchers have determined that both ideas may have been somewhat correct. It has been discovered that the heart contains much of the same tissue found in the human brain and that it may, indeed, be more closely related to human emotion than we used to think. There is a thought that the heart is an extension of the brain.

But we digress.

It was Swiss pastor Johann Kaspar Lavater who introduced the idea that physiognomy revealed specific character traits of people instead of general types. His ideas, outlined in his book Physiognomische Fragmente, may have helped in the eventual "mapping" of the brain by followers of Gall.

It is interesting to study the various published images of the human head, showing areas of the brain believed linked to specific emotions and activities of the body. Few of them show a general consensus of opinion among practitioners.

Nevertheless, during the heyday of physiognomy employers would go so far as to demand a character reference from a local phrenologist to make sure that the potential employee was honest and right for the job. The concept also was used to determine intelligence and criminality. Young people turned to physiognomy in their search for a perfect mate.

We still do all of this today except the assessments are being done by psychics, clairvoyants, astrologers and medical labs searching for narcotics in the blood.

We humans are a peculiar bunch. The more things change the more they stay the same.