Mystery Blast At Chicago

By James Donahue

It began as a typical summer night at the Chicago docks, July 10, 1890. The crack Union Company steamship Tioga was in port, her engine still burping excess steam from a fast run from Buffalo, and the stevedores hard at work removing cargo from her holds. As many as sixty man may have been working on or in the steamer that night, many of them there to unload of wealth of cargo consisting of general merchandise and barrels of petroleum products. There had been a change of shift. The nighttime stevedores, who received an hourly pay had gone home. The night crew, all on monthly salaries and all blacks, were now on the job These men were stripped to the waist as they hoisted the heavy containers from the belly of the iron ship. As darkness began to build the ship’s porter, William Palmer, lit kerosene lanterns so that the unloading could continue through the night.

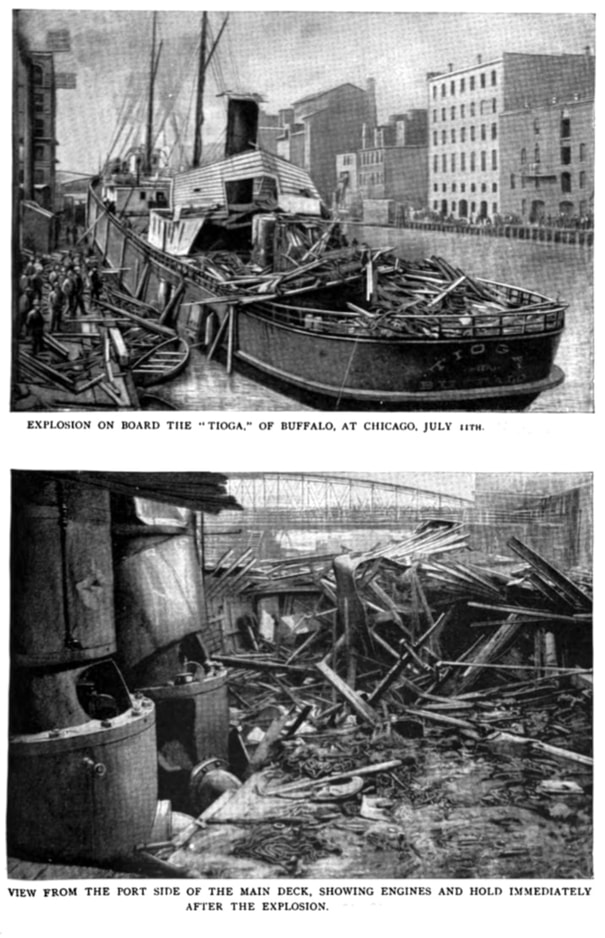

Palmer left the hold and was in another part of the boat when the stern was wracked by a violent explosion and flash fire at 7:32 PM. An estimated twenty-seven men died and many others were badly hurt. The blast was so powerful that it knocked other workers in the forward hold and on the nearby dock off their feet. Witnesses said the wooden deck of the vessel was lifted. The explosion also caused extensive damage to the dock and shattered windows in buildings on both sides of the river.

Strangely enough, the cause of the explosion and a second blast that left two more workers seriously burned the next day was never explained. The mostly commonly accepted theory was that fumes from some of the barrels of oil were ignited when workers brought kerosene lamps into the hold at dusk. L. Scott, a workman who survived, said he left the hold to get some air just minutes before the blast. He said the smell of kerosene was choking him. “The air was very strong,” he said. But Capt. Austin A. Phelps wouldn’t accept that story. “We had no gasoline or naphtha aboard. We did have one hundred barrels of crude petroleum in there, but that would not have exploded. The remainder of the cargo was general merchandise, of which only the rear deck load had been taken off.”

Phelps said the boiler didn’t explode and he objected to a rumor that the vessel might have been sabotaged by two former crew members who had been put ashore at Buffalo. “Two of my men were taken sick in Buffalo. I had to ship two new men in their stead. Aside from these two men, I have had all my men for several years. My crew was composed of twenty-five men, only two of whom were killed.” The dead sailors were identified as lookout E. Levally and watchman William Cuthburn, both of Buffalo. Second engineer George Haige, also of Buffalo, was so badly injured that he died a few days later in a Chicago hospital. Among the others killed were Frank Burns, a steamfitter, who went aboard to visit the engineer moments before the explosion, and John Neill, stevedore foreman, who was the only man who knew how many people were at work on the Tioga when the explosion occurred. Neill’s death made it almost impossible for authorities to get an accurate count or identification of the dead. Some bodies were blown away from the ship and into the river.

The gruesome job of recovering bodies was delayed until the hull was pumped free of water. The pumps were still running the following afternoon when workers Hans Christiansen and Thomas Johnson, from the wrecking crew, went into the hold with a lantern to clean out a clogged suction pipe. Their lantern apparently caused a second explosion. Both men were pulled from the hold alive but were seriously burned and bruised. Even though she was badly damaged, the Tioga was rebuilt and continued working the lakes for many years. She ended her days when she stranded off Eagle River on Lake Superior during a November storm in 1919.

By James Donahue

It began as a typical summer night at the Chicago docks, July 10, 1890. The crack Union Company steamship Tioga was in port, her engine still burping excess steam from a fast run from Buffalo, and the stevedores hard at work removing cargo from her holds. As many as sixty man may have been working on or in the steamer that night, many of them there to unload of wealth of cargo consisting of general merchandise and barrels of petroleum products. There had been a change of shift. The nighttime stevedores, who received an hourly pay had gone home. The night crew, all on monthly salaries and all blacks, were now on the job These men were stripped to the waist as they hoisted the heavy containers from the belly of the iron ship. As darkness began to build the ship’s porter, William Palmer, lit kerosene lanterns so that the unloading could continue through the night.

Palmer left the hold and was in another part of the boat when the stern was wracked by a violent explosion and flash fire at 7:32 PM. An estimated twenty-seven men died and many others were badly hurt. The blast was so powerful that it knocked other workers in the forward hold and on the nearby dock off their feet. Witnesses said the wooden deck of the vessel was lifted. The explosion also caused extensive damage to the dock and shattered windows in buildings on both sides of the river.

Strangely enough, the cause of the explosion and a second blast that left two more workers seriously burned the next day was never explained. The mostly commonly accepted theory was that fumes from some of the barrels of oil were ignited when workers brought kerosene lamps into the hold at dusk. L. Scott, a workman who survived, said he left the hold to get some air just minutes before the blast. He said the smell of kerosene was choking him. “The air was very strong,” he said. But Capt. Austin A. Phelps wouldn’t accept that story. “We had no gasoline or naphtha aboard. We did have one hundred barrels of crude petroleum in there, but that would not have exploded. The remainder of the cargo was general merchandise, of which only the rear deck load had been taken off.”

Phelps said the boiler didn’t explode and he objected to a rumor that the vessel might have been sabotaged by two former crew members who had been put ashore at Buffalo. “Two of my men were taken sick in Buffalo. I had to ship two new men in their stead. Aside from these two men, I have had all my men for several years. My crew was composed of twenty-five men, only two of whom were killed.” The dead sailors were identified as lookout E. Levally and watchman William Cuthburn, both of Buffalo. Second engineer George Haige, also of Buffalo, was so badly injured that he died a few days later in a Chicago hospital. Among the others killed were Frank Burns, a steamfitter, who went aboard to visit the engineer moments before the explosion, and John Neill, stevedore foreman, who was the only man who knew how many people were at work on the Tioga when the explosion occurred. Neill’s death made it almost impossible for authorities to get an accurate count or identification of the dead. Some bodies were blown away from the ship and into the river.

The gruesome job of recovering bodies was delayed until the hull was pumped free of water. The pumps were still running the following afternoon when workers Hans Christiansen and Thomas Johnson, from the wrecking crew, went into the hold with a lantern to clean out a clogged suction pipe. Their lantern apparently caused a second explosion. Both men were pulled from the hold alive but were seriously burned and bruised. Even though she was badly damaged, the Tioga was rebuilt and continued working the lakes for many years. She ended her days when she stranded off Eagle River on Lake Superior during a November storm in 1919.