CRISPR – Possible Answer To GMO Dilemma

By James Donahue

The growing world rejection of Monsanto’s genetically modified foods may have an alternative to creating more and improved cuisine without having to swallow the poison that comes with it. Instead of GMO the new word may be CRISPR.

That acronym stands for a new type of genetic engineering technology that goes by the weird title: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.

If the proper name blows your mind, don’t try to wade through attempts to explain how it all works. All we can say is that it does not involve the insertion of genes from foreign species into either plants or animals to produce altered foods.

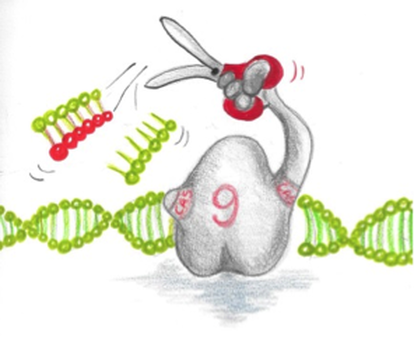

Instead, researchers are using a natural enzyme called Cas9 to “cut, edit or remove genes” from a specific region of the DNA in a plant or animal to achieve a desired change.

The first CRISPR food that may be on the market if a patent-pending, non-browning mushroom gets a final approval. The mushroom was developed by Yinong Yang, a Penn State professor of plant pathology. Yang has been notified that the new mushroom does not require approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture because it is a natural food product without foreign DNA integration in its genome.

Right on the heels of Yang's new mushroom may be a CRISPR-Cas9-edited variety of corn being developed by DuPont Pioneer. If these two products meet final approval, food researchers believe this may be the beginning of a massive new field of meats, grains, fruits, mushrooms and vegetables designed to fill a fast-growing world demand for food in a growing hostile farming environment.

The USDA ruling is only the first hurdle for CRISPR food technology. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration also must put these foods under the microscope. Once introduced to the world market, it will be up to consumers to determine if the food is something they can accept.

The stigma of the Monsanto GMO brand, which has been filling grocery shelves with foods laced with poisonous insecticides, herbicides, antibiotics and other chemicals, may make it difficult to sell CRISPR foods on the open market.

Yet agriculturalists agree that there is a growing need to find ways to produce more and improved foods in less time to meet a growing world need to feed the hungry. As farms are slammed by changing weather patterns, floods, extreme heat and growing areas of desertification, researchers are looking for every trick in the book to beat the clock in this field.

CRISPR may not be the final solution, but it appears to be a step in the right direction.

By James Donahue

The growing world rejection of Monsanto’s genetically modified foods may have an alternative to creating more and improved cuisine without having to swallow the poison that comes with it. Instead of GMO the new word may be CRISPR.

That acronym stands for a new type of genetic engineering technology that goes by the weird title: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.

If the proper name blows your mind, don’t try to wade through attempts to explain how it all works. All we can say is that it does not involve the insertion of genes from foreign species into either plants or animals to produce altered foods.

Instead, researchers are using a natural enzyme called Cas9 to “cut, edit or remove genes” from a specific region of the DNA in a plant or animal to achieve a desired change.

The first CRISPR food that may be on the market if a patent-pending, non-browning mushroom gets a final approval. The mushroom was developed by Yinong Yang, a Penn State professor of plant pathology. Yang has been notified that the new mushroom does not require approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture because it is a natural food product without foreign DNA integration in its genome.

Right on the heels of Yang's new mushroom may be a CRISPR-Cas9-edited variety of corn being developed by DuPont Pioneer. If these two products meet final approval, food researchers believe this may be the beginning of a massive new field of meats, grains, fruits, mushrooms and vegetables designed to fill a fast-growing world demand for food in a growing hostile farming environment.

The USDA ruling is only the first hurdle for CRISPR food technology. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration also must put these foods under the microscope. Once introduced to the world market, it will be up to consumers to determine if the food is something they can accept.

The stigma of the Monsanto GMO brand, which has been filling grocery shelves with foods laced with poisonous insecticides, herbicides, antibiotics and other chemicals, may make it difficult to sell CRISPR foods on the open market.

Yet agriculturalists agree that there is a growing need to find ways to produce more and improved foods in less time to meet a growing world need to feed the hungry. As farms are slammed by changing weather patterns, floods, extreme heat and growing areas of desertification, researchers are looking for every trick in the book to beat the clock in this field.

CRISPR may not be the final solution, but it appears to be a step in the right direction.