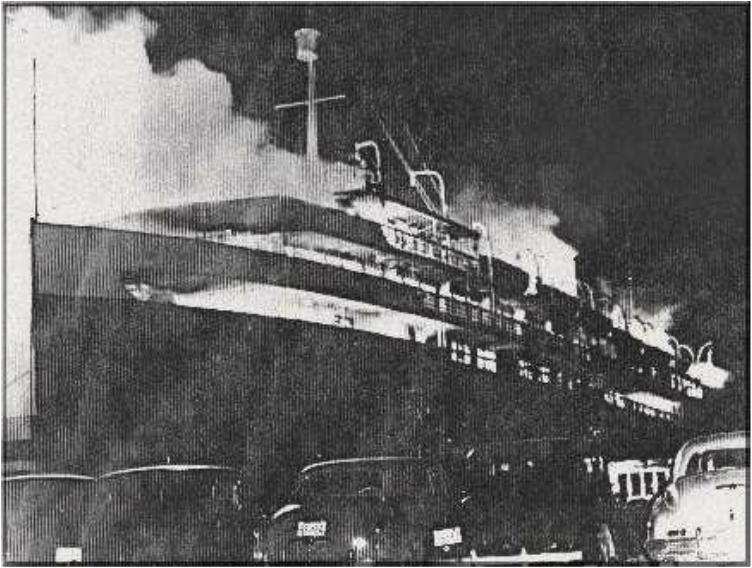

The Burning Of The Noronic

By James Donahue

Sanford Newman, a Cleveland man participating in a special August excursion aboard the Great Lakes passenger liner Noronic on Sept. 16, 1949, later said he thought it was about 2:30 a.m. when the fire that destroyed the ship was discovered.

Newman and his wife were among the 524 passengers taking advantage of a special late-season rate on the Canada Steamship Line vessel. While other passengers were partying, the Newmans and friends were engaged in a hot game of cards in a parlor on C Deck, somewhere amidships.

The ship was docked at Toronto for the night.

That was when he said he heard a commotion in the hall and someone yelled that they could smell smoke. "I was among the men who went to the rear of the boat to find out what it was," Newman said.

As he ran along the starboard corridor Newman said the smell of smoke got very strong. "We found the fire in what may have been a linen closet on the (port) side of the ship. Two bus boys were already there trying to put it out with a fire extinguisher. I heard one of them say, 'Youd better go and get help.' Then the smoke choked me up."

"I ran back to the parlor to warn the others," Newman said.

Because they were awake and warned on time, the Cleveland card players all escaped the disaster that followed.

Another witness outside the burning linen closet was Ben Kosman, a Cleveland businessman, who also was traveling with friends.

"I was just going along the passageway when I smelled smoke," Kosman said. "Then I saw a couple of the bellboys coming along with fire extinguishers so I went along to the cabin about in the center. They opened the door. They shouldn't have done that. The flames roared out. They might have been trying to put out hell with fountain pens. It was no use, and they couldn't, or didn't, close the door again."

The fire swept the 32-year-old ship so quickly that many passengers were trapped in their cabins. Some were believed to have died in their sleep, never realizing that the ship was burning.

Bedlam broke out and survivors later told of magnificent acts of heroism as well as dark stories of cowardice as people fought to escape the smoke-filled corridors.

Capt. William Taylor was counted among the heroes. Survivors later told a board of inquiry how Taylor was seen among the crew members, fighting the fire with water. Then, when he realized that the fire was out of control, Taylor ran along the deck, smashing windows and portholes, helping trapped passengers escape their cabins. The fire was blocking normal exits through the doors to the inside passageways.

Steward Chic Yates said he was with Taylor during a search of the ship's cabins. "We checked the steward's quarters, the engine room and the cabins. Everybody was out.

"On the way back it was really bad. Sparks were flying and the smoke was thick. I tripped over a woman who was lying across the passageway. The captain and I carried her to the side of the ship. We tied a rope around her and lowered her into a launch."

Yates said people were jumping over the side. He said when they took a final look through the ship they realized they could not enter the vessel again. "The ship was ablaze to the superstructure," he said.

Taylor later was treated for exhaustion and burns aboard the Kingston, a sister ship docked nearby. His burns were apparently serious because the official inquiry was delayed for several days until he was well enough to testify.

Sylvia Carpenter of Detroit said she was trying to help people climb off the burning ship to the dock below. "Someone had thrown a rope ladder over the dockside, but it was all tangled up. Then a rope was tossed over the rail. I put a hitch knot in it to hold it to a stanchion. As I did, three men pushed in front of me and shoved some screaming women out of the way. The men went down the rope," Carpenter said.

After that, she said she helped the other women climb to safety before making her own escape.

Elsewhere on the ship people were exhibiting blind hysteria.

Alberta Agala of Detroit said: "the Noronic's A deck was a complete scene of panic. There was a mob of men and women surging back and forth. Men were pushing women around and many were knocked to the floor. There was so much panic I don't know how these people got segregated to find a way to safety. I slid down a rope."

C. E. Metcal of Columbus, Ohio, said he watched people jump from the ship. Some fell to their death. "It was terrible. Some of the people who jumped landed on the dock far below. Others landed in the water. The police and firemen did a marvelous job using boats to rescue the people who leaped into the water," he said.

There were horror stories from people who nearly were trapped to die in their cabins. Mrs. Mat J. Hackman of Covington, Kentucky, said she woke up about 2 a.m. and found her room ablaze. "I screamed to my husband to wake up. The heat was terrible, and people were screaming all about us. We got outside on the deck and jumped overboard into the water. I could see (other) people jumping into the water and some of them were on fire."

Emil Dahlke of Hazel Park said he and his wife were awakened by someone pounding on the door of their cabin. "I heard the awful word, 'Fire!' ringing down the hallways. It sent a chill through me. I flung open our cabin door and was met by a blast of heat and flame. I ran back into our cabin for my wife and for a few moments we just stood there. I could see the horror on her face.

"There was no time to dress," Dahlke said. "We ran to the stateroom window and pushed out a screen. A deckhand grabbed our shoulders and pulled us through the small port hole.

"Hundreds were rushing around the ship screaming and crying out for their relatives and friends. It was complete panic and women were knocked down in the struggle. All I could think of was getting my wife from the inferno. We ran to the side of the ship and I slid down a hawser with my wife on my shoulder."

When the fire was out, the vessel was left a partly sunken hulk of smoldering ruin. Toronto Star reporter Edwin Feeney was the first newsman allowed aboard on the following day. He wrote:

"It was a horrible picture of charred remains amid foot deep embers and melted glass. There wasn't a wooden partition standing. There was no wooden furniture or upholstery unburned. No stairways remained save one at the bow of the ship. Every pane of glass has been melted by the intense heat.

"Fire Chief Art Smith said his men found victims in every position. Many had their lives snuffed out without waking. One young woman, wrapped in a blanket, had her face burned, but her body was not touched. Upper bunks fell crashing down on victims below. Firemen searching the ruins found human remains between scorched mattresses.

"Priests from St. Michael's Cathedral, Father Vincent Foy and Father Bernard Kyte, stepped about the debris, sometimes almost knee deep.

"The steel stanchions were bent in every shape. The decks crumpled and buckled from the heat, make progress hazardous for the firemen seeking the dead," Feeley wrote.

The death toll was estimated at 139, although nobody knew for sure. The figure varies among the records of the day.

It was determined that the fire either started in the linen closet on C Deck or in an adjoining women's rest room, possibly from a carelessly thrown cigarette.

Investigators also learned that the crew members who first discovered the fire lost precious minutes trying to fight it on their own before sounding an alarm. And that alarm was only sent to the bridge and other key parts of the ship.

Nobody sounded an alarm that would have aroused the passengers. It was found that no alarm was sent to the Toronto Fire Department by the crew, and the ship's water lines were never connected to the city water mains.

Of a crew of 170, only 16 were on duty when the fire broke out. All of the crew members familiar with the ship and knew the escape routes got out alive.

Despite his acts of heroism, Captain Taylor shouldered blame for the failures. He lost his license for one year for failing to provide proper leadership. The Canadian government also was criticized for allowing the vessel to operate without fireproof bulkheads and an automatic fire alarm system.

Damage suits were settled for more than two million dollars.

By James Donahue

Sanford Newman, a Cleveland man participating in a special August excursion aboard the Great Lakes passenger liner Noronic on Sept. 16, 1949, later said he thought it was about 2:30 a.m. when the fire that destroyed the ship was discovered.

Newman and his wife were among the 524 passengers taking advantage of a special late-season rate on the Canada Steamship Line vessel. While other passengers were partying, the Newmans and friends were engaged in a hot game of cards in a parlor on C Deck, somewhere amidships.

The ship was docked at Toronto for the night.

That was when he said he heard a commotion in the hall and someone yelled that they could smell smoke. "I was among the men who went to the rear of the boat to find out what it was," Newman said.

As he ran along the starboard corridor Newman said the smell of smoke got very strong. "We found the fire in what may have been a linen closet on the (port) side of the ship. Two bus boys were already there trying to put it out with a fire extinguisher. I heard one of them say, 'Youd better go and get help.' Then the smoke choked me up."

"I ran back to the parlor to warn the others," Newman said.

Because they were awake and warned on time, the Cleveland card players all escaped the disaster that followed.

Another witness outside the burning linen closet was Ben Kosman, a Cleveland businessman, who also was traveling with friends.

"I was just going along the passageway when I smelled smoke," Kosman said. "Then I saw a couple of the bellboys coming along with fire extinguishers so I went along to the cabin about in the center. They opened the door. They shouldn't have done that. The flames roared out. They might have been trying to put out hell with fountain pens. It was no use, and they couldn't, or didn't, close the door again."

The fire swept the 32-year-old ship so quickly that many passengers were trapped in their cabins. Some were believed to have died in their sleep, never realizing that the ship was burning.

Bedlam broke out and survivors later told of magnificent acts of heroism as well as dark stories of cowardice as people fought to escape the smoke-filled corridors.

Capt. William Taylor was counted among the heroes. Survivors later told a board of inquiry how Taylor was seen among the crew members, fighting the fire with water. Then, when he realized that the fire was out of control, Taylor ran along the deck, smashing windows and portholes, helping trapped passengers escape their cabins. The fire was blocking normal exits through the doors to the inside passageways.

Steward Chic Yates said he was with Taylor during a search of the ship's cabins. "We checked the steward's quarters, the engine room and the cabins. Everybody was out.

"On the way back it was really bad. Sparks were flying and the smoke was thick. I tripped over a woman who was lying across the passageway. The captain and I carried her to the side of the ship. We tied a rope around her and lowered her into a launch."

Yates said people were jumping over the side. He said when they took a final look through the ship they realized they could not enter the vessel again. "The ship was ablaze to the superstructure," he said.

Taylor later was treated for exhaustion and burns aboard the Kingston, a sister ship docked nearby. His burns were apparently serious because the official inquiry was delayed for several days until he was well enough to testify.

Sylvia Carpenter of Detroit said she was trying to help people climb off the burning ship to the dock below. "Someone had thrown a rope ladder over the dockside, but it was all tangled up. Then a rope was tossed over the rail. I put a hitch knot in it to hold it to a stanchion. As I did, three men pushed in front of me and shoved some screaming women out of the way. The men went down the rope," Carpenter said.

After that, she said she helped the other women climb to safety before making her own escape.

Elsewhere on the ship people were exhibiting blind hysteria.

Alberta Agala of Detroit said: "the Noronic's A deck was a complete scene of panic. There was a mob of men and women surging back and forth. Men were pushing women around and many were knocked to the floor. There was so much panic I don't know how these people got segregated to find a way to safety. I slid down a rope."

C. E. Metcal of Columbus, Ohio, said he watched people jump from the ship. Some fell to their death. "It was terrible. Some of the people who jumped landed on the dock far below. Others landed in the water. The police and firemen did a marvelous job using boats to rescue the people who leaped into the water," he said.

There were horror stories from people who nearly were trapped to die in their cabins. Mrs. Mat J. Hackman of Covington, Kentucky, said she woke up about 2 a.m. and found her room ablaze. "I screamed to my husband to wake up. The heat was terrible, and people were screaming all about us. We got outside on the deck and jumped overboard into the water. I could see (other) people jumping into the water and some of them were on fire."

Emil Dahlke of Hazel Park said he and his wife were awakened by someone pounding on the door of their cabin. "I heard the awful word, 'Fire!' ringing down the hallways. It sent a chill through me. I flung open our cabin door and was met by a blast of heat and flame. I ran back into our cabin for my wife and for a few moments we just stood there. I could see the horror on her face.

"There was no time to dress," Dahlke said. "We ran to the stateroom window and pushed out a screen. A deckhand grabbed our shoulders and pulled us through the small port hole.

"Hundreds were rushing around the ship screaming and crying out for their relatives and friends. It was complete panic and women were knocked down in the struggle. All I could think of was getting my wife from the inferno. We ran to the side of the ship and I slid down a hawser with my wife on my shoulder."

When the fire was out, the vessel was left a partly sunken hulk of smoldering ruin. Toronto Star reporter Edwin Feeney was the first newsman allowed aboard on the following day. He wrote:

"It was a horrible picture of charred remains amid foot deep embers and melted glass. There wasn't a wooden partition standing. There was no wooden furniture or upholstery unburned. No stairways remained save one at the bow of the ship. Every pane of glass has been melted by the intense heat.

"Fire Chief Art Smith said his men found victims in every position. Many had their lives snuffed out without waking. One young woman, wrapped in a blanket, had her face burned, but her body was not touched. Upper bunks fell crashing down on victims below. Firemen searching the ruins found human remains between scorched mattresses.

"Priests from St. Michael's Cathedral, Father Vincent Foy and Father Bernard Kyte, stepped about the debris, sometimes almost knee deep.

"The steel stanchions were bent in every shape. The decks crumpled and buckled from the heat, make progress hazardous for the firemen seeking the dead," Feeley wrote.

The death toll was estimated at 139, although nobody knew for sure. The figure varies among the records of the day.

It was determined that the fire either started in the linen closet on C Deck or in an adjoining women's rest room, possibly from a carelessly thrown cigarette.

Investigators also learned that the crew members who first discovered the fire lost precious minutes trying to fight it on their own before sounding an alarm. And that alarm was only sent to the bridge and other key parts of the ship.

Nobody sounded an alarm that would have aroused the passengers. It was found that no alarm was sent to the Toronto Fire Department by the crew, and the ship's water lines were never connected to the city water mains.

Of a crew of 170, only 16 were on duty when the fire broke out. All of the crew members familiar with the ship and knew the escape routes got out alive.

Despite his acts of heroism, Captain Taylor shouldered blame for the failures. He lost his license for one year for failing to provide proper leadership. The Canadian government also was criticized for allowing the vessel to operate without fireproof bulkheads and an automatic fire alarm system.

Damage suits were settled for more than two million dollars.

Welcome to the new site for The Mind of James Donahue. This site will still include stories about politics, shipwrecks, spiritual thought and history. The site will continue to follow its original vein . . . to challenge readers to consider everything from a different perspective. Nothing is as it appears. Challenge everything. Never accept what we are told as truth until we test its validity.