The Great Atlantic Disaster

By James Donahue

For years there was an old joke about how Lake Erie swallowed the Atlantic. It was a sick joke at best since it referred to one of the worst disasters in the history of the Great Lakes. That event was the sinking of the passenger steamer Atlantic and loss of between 130 and 250 lives following a collision with the propeller Ogdensburg.

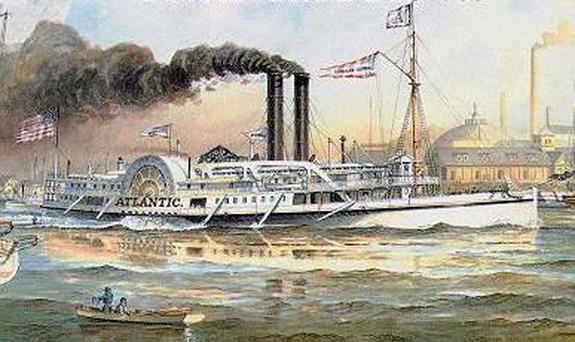

It happened in 1852, back in the days when steamboats were distinguished from propellers because they were driven by large wheels mounted on their sides. The Atlantic was such a boat.

Long by 267 feet, low and sleek in appearance, the Atlantic was just four years old and remembered as among the most luxurious and fastest steamships on the lakes. The first class state rooms were said to have been decorated with gold gilding, tapestries and carved rosewood furnishings. Her owners boasted that the boat could steam from Buffalo to Detroit in just over 16 hours.

The Atlantic was built for Capt. E. B. Ward of Detroit in 1849 by J. L. Wolverton in Newport, the old name for Marine City, Michigan.

The collision should not have happened. The Atlantic, carrying an estimated 600 passengers, was steaming westward toward Detroit, and the Ogdensburg, a smaller, propeller-driven vessel, was traveling north toward the Canadian shore. Witnesses said the weather was slightly hazy but the lake was calm and the stars were visible when the Ogdensburg struck the ill-fated Atlantic amidships at about 2 a.m. Other reports stated that there was fog in the lake at the time of the wreck.

Amund Eidsmoe, one of 132 Norwegian immigrants sleeping on the open deck of the overcrowded boat, gave the following graphic description of what it was like to have the bow of the other ship strike the boat.

“The deck was crowded with every conceivable thing: baggage, new wagons and much other stuff. So we lay down to rest but sleep was not of long duration. . . We were awakened by a loud crash and saw a large beam fall down upon a Norwegian woman of our company. It crushed several bones and completely tore the head off a little baby that lay at her side.

“Another ship had collided with ours and knocked a large hole in the side of the Atlantic so that a flood of water rushed into the cabins. People came up as thick and fast as they could crowd themselves.”

Eidsmoe said for some unknown reason, the boat’s crew did all it could to block their escape from the flooding below. “The sailors became absolutely raving and tried to get as many killed as possible. When they saw that people crowded up they struck them on the heads and shoulders to drive them down again. When this did not help, they took and raised the stairway up on end so the people fell down backwards again. Then they jerked the ladder up on the deck. All hopes were gone for those that were underneath.”

Crew members explained during a hearing held before an investigative board that Captain Petty was attempting to run the ship toward shallow water at the Canadian coast. The Norwegian emmigrants, who could not speak English, were attempting to jump overboard without life preservers and this was what Eidsmoe mistook for the effort by the ship's crew to force passengers back to their cabins and to their death.

Erik Thorstad, another Norwegian, was sleeping in one of the ship’s cabins when he was awakened by a loud crash that he assumed was the noise of a collision. He said he went on deck to ask what happened but could not get any answers.

“I could not believe that there was any immediate danger, for the engines were still in motion,” Thorstad said. “I went up to the top deck, and then I was convinced at once that the steamer must have been damaged, for many people were lowering about with the greatest haste.”

He said he soon realized that the Atlantic was sinking fast and that the water was rising up through the decks below him. He scrambled with the other passengers up the various stairways.

“We thereupon climbed up to the third deck, where the pilot was at the wheel,” Thorstad said. “I had altogether given up hope of being saved, for the boat began to sink more and more, and the water almost reached up there.

“While we stood thus, much distressed, we saw several people putting out a small boat, whereupon we at once hastened to help. We succeeded in getting it well out, and I was one of the first to get into the boat. When there were as many as the boat could hold, it was fortunately pushed away from the steamer. As oars were wanting, we rowed with our hands, and several bailed water from the boat with their hats.”

After the collision, both steamers separated and for a while continued on their course as if nothing had happened. The Atlantic came to a stop, however, after the water flooded her engines. Because she was still under way, attempts by the crew and passengers to launch life boats failed.

There were reports of widespread panic, with many people wildly jumping overboard. The master of the Atlantic, Captain Petty, was injured when he fell into a yawl shortly after the collision but remained active in attempting to get passengers transferred to the Ogdensburg. Passengers were urged to grab pieces of furniture to use like life preservers in the water. A lot of people, especially the Norwegians who could not understand English, perished as the big steamer sank stern first in about 165 feet of water.

Since the Atlantic was longer than the water was deep, a portion of the boat was settled on the bottom of Lake Erie while the bow remained afloat for hours with people clinging to it.

Captain Richardson of the Ogdensburg got his vessel turned around and with the pumps keeping ahead of a serious leak in the hull, returned to the scene of the disaster. The vessel stood by until daylight, then began a rescue operation. Survivors were removed from the Atlantic's stern and pulled from the water.

Because the purser was lost with the boat’s manifest, there was no accurate description of the number of passengers on the Atlantic that night, or how many were lost. Estimates ranged from as high was 600 to as low as 250. Beers History of the Great Lakes concluded that the actual number may have been as low as 131.

Captain Petty was hospitalized for treatment of his injuries after reaching shore.

The cause of the disaster was never officially determined, although fog was calculated to have been a major factor. The kerosene lamps used to light ships in those early days were not very effective. The board of inquiry ruled that both vessels shared the blame.

For years after the wreck, divers made daring attempts to salvage money and jewelry said to have been lost with the Atlantic. Many of them died trying.

Of further interest, the Ogdensburg also was sunk in a collision on Lake Erie. It happened in 1864, just 12 years later, when the propeller collided with the schooner Snow Bird and foundered. This time the passengers and crew escaped.

By James Donahue

For years there was an old joke about how Lake Erie swallowed the Atlantic. It was a sick joke at best since it referred to one of the worst disasters in the history of the Great Lakes. That event was the sinking of the passenger steamer Atlantic and loss of between 130 and 250 lives following a collision with the propeller Ogdensburg.

It happened in 1852, back in the days when steamboats were distinguished from propellers because they were driven by large wheels mounted on their sides. The Atlantic was such a boat.

Long by 267 feet, low and sleek in appearance, the Atlantic was just four years old and remembered as among the most luxurious and fastest steamships on the lakes. The first class state rooms were said to have been decorated with gold gilding, tapestries and carved rosewood furnishings. Her owners boasted that the boat could steam from Buffalo to Detroit in just over 16 hours.

The Atlantic was built for Capt. E. B. Ward of Detroit in 1849 by J. L. Wolverton in Newport, the old name for Marine City, Michigan.

The collision should not have happened. The Atlantic, carrying an estimated 600 passengers, was steaming westward toward Detroit, and the Ogdensburg, a smaller, propeller-driven vessel, was traveling north toward the Canadian shore. Witnesses said the weather was slightly hazy but the lake was calm and the stars were visible when the Ogdensburg struck the ill-fated Atlantic amidships at about 2 a.m. Other reports stated that there was fog in the lake at the time of the wreck.

Amund Eidsmoe, one of 132 Norwegian immigrants sleeping on the open deck of the overcrowded boat, gave the following graphic description of what it was like to have the bow of the other ship strike the boat.

“The deck was crowded with every conceivable thing: baggage, new wagons and much other stuff. So we lay down to rest but sleep was not of long duration. . . We were awakened by a loud crash and saw a large beam fall down upon a Norwegian woman of our company. It crushed several bones and completely tore the head off a little baby that lay at her side.

“Another ship had collided with ours and knocked a large hole in the side of the Atlantic so that a flood of water rushed into the cabins. People came up as thick and fast as they could crowd themselves.”

Eidsmoe said for some unknown reason, the boat’s crew did all it could to block their escape from the flooding below. “The sailors became absolutely raving and tried to get as many killed as possible. When they saw that people crowded up they struck them on the heads and shoulders to drive them down again. When this did not help, they took and raised the stairway up on end so the people fell down backwards again. Then they jerked the ladder up on the deck. All hopes were gone for those that were underneath.”

Crew members explained during a hearing held before an investigative board that Captain Petty was attempting to run the ship toward shallow water at the Canadian coast. The Norwegian emmigrants, who could not speak English, were attempting to jump overboard without life preservers and this was what Eidsmoe mistook for the effort by the ship's crew to force passengers back to their cabins and to their death.

Erik Thorstad, another Norwegian, was sleeping in one of the ship’s cabins when he was awakened by a loud crash that he assumed was the noise of a collision. He said he went on deck to ask what happened but could not get any answers.

“I could not believe that there was any immediate danger, for the engines were still in motion,” Thorstad said. “I went up to the top deck, and then I was convinced at once that the steamer must have been damaged, for many people were lowering about with the greatest haste.”

He said he soon realized that the Atlantic was sinking fast and that the water was rising up through the decks below him. He scrambled with the other passengers up the various stairways.

“We thereupon climbed up to the third deck, where the pilot was at the wheel,” Thorstad said. “I had altogether given up hope of being saved, for the boat began to sink more and more, and the water almost reached up there.

“While we stood thus, much distressed, we saw several people putting out a small boat, whereupon we at once hastened to help. We succeeded in getting it well out, and I was one of the first to get into the boat. When there were as many as the boat could hold, it was fortunately pushed away from the steamer. As oars were wanting, we rowed with our hands, and several bailed water from the boat with their hats.”

After the collision, both steamers separated and for a while continued on their course as if nothing had happened. The Atlantic came to a stop, however, after the water flooded her engines. Because she was still under way, attempts by the crew and passengers to launch life boats failed.

There were reports of widespread panic, with many people wildly jumping overboard. The master of the Atlantic, Captain Petty, was injured when he fell into a yawl shortly after the collision but remained active in attempting to get passengers transferred to the Ogdensburg. Passengers were urged to grab pieces of furniture to use like life preservers in the water. A lot of people, especially the Norwegians who could not understand English, perished as the big steamer sank stern first in about 165 feet of water.

Since the Atlantic was longer than the water was deep, a portion of the boat was settled on the bottom of Lake Erie while the bow remained afloat for hours with people clinging to it.

Captain Richardson of the Ogdensburg got his vessel turned around and with the pumps keeping ahead of a serious leak in the hull, returned to the scene of the disaster. The vessel stood by until daylight, then began a rescue operation. Survivors were removed from the Atlantic's stern and pulled from the water.

Because the purser was lost with the boat’s manifest, there was no accurate description of the number of passengers on the Atlantic that night, or how many were lost. Estimates ranged from as high was 600 to as low as 250. Beers History of the Great Lakes concluded that the actual number may have been as low as 131.

Captain Petty was hospitalized for treatment of his injuries after reaching shore.

The cause of the disaster was never officially determined, although fog was calculated to have been a major factor. The kerosene lamps used to light ships in those early days were not very effective. The board of inquiry ruled that both vessels shared the blame.

For years after the wreck, divers made daring attempts to salvage money and jewelry said to have been lost with the Atlantic. Many of them died trying.

Of further interest, the Ogdensburg also was sunk in a collision on Lake Erie. It happened in 1864, just 12 years later, when the propeller collided with the schooner Snow Bird and foundered. This time the passengers and crew escaped.